Sunday, 16 October 2022

Saturday, 15 October 2022

Christotelic Preaching: A Plea for Hermeneutical Integrity and Missional Passion

By Daniel I. Block [1]

[Daniel I. Block is Gunther H. Knoedler Professor Emeritus of Old Testament at Wheaton College. He earned his DPhil in the School of Archaeology and Oriental Studies at the University of Liverpool, United Kingdom. Dr. Block has written numerous articles and books including The Book of Ezekiel, vol. 1 and 2 in the New International Commentary of the Old Testament Series (Eerdmans, 1997, 1998); Judges, Ruth (B&H, 1999); Deuteronomy in the NIV Application Commentary series (Zondervan, 2012); and For the Glory of God: A Biblical Theology of Worship (Baker Academic, 2014).]

Introduction

Lest readers misunderstand me in the end, my fundamental concern in conversations about preaching is that we proclaim the truth of God with integrity and with the passion of God’s own heart. How to bring these two elements together has been a personal challenge, and as I observe preaching in this country I see this is a crucial issue within evangelicalism today. On the one hand, we have preaching in which the content is true to the word of God, but the divine passion is utterly missing. Sermons are crafted as running commentaries on biblical texts or as lectures on theological topics, and often presented without passion, except perhaps to display the brilliance, wide reading, and rhetorical ingenuity of the preacher. On the other hand, we have firebrands, whose passion ignites the emotions of the audience, but whose presentation is at best a trivial pursuit of biblical truth, and at worst an exercise in empty demagoguery.

How do we resolve this issue, and in so doing end the famine for the word of God in the land (Amos 8:11) and nourish our people with food that transforms and yields life? In my view the answer is Christotelic reading of Scripture and a Christocentric proclamation—or more accurately a Jesuscentered proclamation. This may appear to some as mere semantics, but to me there is a significant difference between Christocentric activity— whether hermeneutical or homiletical—and Jesus-centered activity.

I have been trying to teach and preach the truth of the whole Bible for more than five decades. But academically I have been primarily engaged in teaching the First Testament (my preferred designation for the Hebrew Bible—what you call something matters; ask the publishers). I grew up in a humble place, Borden, Saskatchewan, the ninth of fifteen children in a humble farm family. My parents were very godly people. I will forever hear the words of my mother ringing in my ears. Knowing that I spent most of my time in the First Testament, my mother would often ask, “But do you love Jesus?” That is a great question, and it has served as a constant reminder to me of what we should be passionate about. Notice, she did not ask, “Do you love Christ?”

The more I have thought about it, the more grateful I am that she put it the way she did, for three reasons. First, in the Scriptures Jesus is much more common as a designation for the second person of the Trinity than the title Christ. The former appears more than 900 times,[2] in comparison with the latter, which occurs only 531 times.[3] Second, Jesus is a personal name, in contrast to Christ (ὁ χριστός), which is a title. By definition, a name invites a personal relationship, as opposed to an official epithet, which acknowledges a formal relationship based on status. Third, in the New Testament (NT), the epithet ὁ χριστός functions as a narrow technical term for the eschatological messianic son of David.[4] If we are honest, and if this is what we mean by “messianic,” we could count all the relevant texts in the First Testament on our two hands and two feet. “Christ” is the English rendering of the Greek word that suggests a very narrow role: Jesus, the literal “son of God” (as opposed to the metaphorical use of the phrase for David and his other royal descendants, e.g., Ps 2:7; 89:27–28[26–27]) and royal son of David. This is the anointed one who fulfills YHWH’s promise to David of eternal title to the throne of Israel. David acknowledged the scope of this promise, in that it concerned the distant future (לְמֵרָחוֹק) and represented divine “revelation for humanity” (וְזֹאת תּוֹרַת הָאָדָם, 2 Sam 7:10). In Jesus the Christ the universalization of that promise is realized.

The connotations of the personal name “Jesus” are much more comprehensive. Matthew laid the foundations for our understanding of the name in the first chapter of his Gospel. In the opening lines to the genealogy of Jesus (Matt 1:1) and the formal opening to the birth narrative of Jesus (1:18), the evangelist introduced the principal figure as Jesus Messiah (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός). With the note in verse 16 that he was the son of Mary, who was the wife of Joseph, and the name “Jesus,” the evangelist had announced his identity. However, by adding, “who is called Christ (Anointed One),” he declared Jesus’ status. Interestingly, except for 2:4, where Matthew notes that Herod inquired “where the Messiah was to be born,” after this he never uses this epithet for Jesus, either in the birth narrative or in the following ten chapters. The evangelist hereby recognized that this represented a search by one official concerning the affairs of another official, who potentially threatened his own status. By contrast, Matthew forefronts “Jesus” by naming him 34 times in the narrative that runs from 1:19–10:42.

More particularly, in the first scene of this long narrative the angel of YHWH appeared and announced that Mary had conceived this child supernaturally. In prescribing that she name him Jesus, he offered the divine interpretation of the name, thereby declaring the significance of his birth. In the birth of Jesus the prophetic promise that God would one day dwell among his people again (“Immanuel”) will be fulfilled (vv. 20–23). I find the explanation of the name the angel passed on to Mary particularly intriguing: “You are to give him the name Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins.”

Because “Jesus” is the Greek form of the Hebrew name “Joshua,” many view Jesus as a second Joshua, or Joshua as a type of Christ. But this illustrates precisely what is wrong with a Christocentric hermeneutic. When we look at the First Testament background to the angel’s statement we find that this approach is untenable, for several reasons. First, when Moses assigned the name to the man previously known as Hoshea (Num 13:16), the name Jesus/Joshua said nothing about the man who bore it. Second, unlike the tribal governors in the book of Judges, the book of Joshua, which is named after him, never presents Joshua as a “savior” (מוֹשַׁיעַ, Judg 3:9, 15; cf. 6:36; 12:3) figure. In the battles against the Canaanites Joshua was the antagonist, the aggressor; if anything, the Canaanites needed salvation from him!

Third, as far as we know, Joshua played no role at all in Israel’s supreme and paradigmatic moment of salvation—their rescue from the bondage of slavery in Egypt (Exodus 14–15). To the contrary, as YHWH had declared earlier, the point of the signs and wonders in Egypt and the Israelites’ escape from slavery, was that God’s people, the Egyptians, and the world would know who he (not Moses, or Joshua, or anyone else) was (Exod 6:7; 7:5, 17; 8:22; 10:2; 14:4, 18; 16:12; cf. Deut 4:32–39). The formula that appears dozens of times in the First Testament memorializes this fact: “I am YHWH your God who brought you up out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery” (Exod 20:2). By renaming Hoshea, in a parenthetical clause in Numbers 13:16 Moses testified that this goal had been fulfilled:

Why did Moses change Joshua’s name, Hoshea, which means “He [any god] has saved,” to Yehoshua, which can only mean “YHWH has saved!”? The name says nothing about Joshua, but it says everything about God. The one who rescued Israel was YHWH himself. By defeating Pharaoh and his armies, he had won a great victory over the gods of Egypt (Exod 12:12; Num 33:4), and in so doing declared that he alone is God—there is no other! (Deut 4:32–40). Neither Moses nor Joshua would have been pleased to hear us link Jesus to Joshua or Joshua to the exodus and then to forget that the One who had rescued them from the Egyptians was YHWH.

Using the language of Israel’s rescue from Egypt, the angel announced a salvation far greater than Israel’s rescue from slavery to Pharaoh: Jesus came to rescue his people from their sins! But there is more. The One who had been conceived in Mary’s womb was the very One who had introduced himself by name to Moses in Exodus 3–4. Just as the events surrounding Israel’s exodus from Egypt had revealed YHWH as God in all his grace and glory, so the birth of Jesus and his saving work would reveal him as God in all his grace and glory ( John 1:14).

The other title that Matthew 1:23 gives to Jesus confirms this identification of Jesus with God: he is Immanuel, which means, “God is with us!” Jesus was not merely a symbol of God’s presence (like prophets and priests); no, he embodied divine presence. This was what the angel of YHWH announced, “Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord (read YHWH)” (Luke 2:11, NIV modified). I read the last epithet as a reference to YHWH, the Savior and covenant God of Israel, whose name is preserved in “Jesus” (Hebrew, “Yehoshua”), which means “YHWH saves.” Among many other profound Christological themes, the NT makes two fundamental points about Jesus: Yes, he is the Davidic Messiah (“Christ”); but yes, he is also God. The statement by the angel to the shepherds on the hills of Bethlehem reinforces both points (Luke 2:11). Unless we are thoroughly steeped in the First Testament we will not connect these dots ( John 1:23; Rom 10:13; etc.).[5] But having connected the dots means that when I preach YHWH, I preach Jesus, for in him the word became flesh and dwelt among us and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father full of grace and truth ( John 1:14, πολυέλεος καὶ ἀληθινὸς; = Hebrew רַב־חֶסֶד וֶאֱמֶת; cf. Exod 34:6; Num 14:18; Ps 85:15 Greek πλήρης χάριτος καὶ ἀληθείας). There is no need to resort to cheap and trivializing typologizing and Christologizing, which often actually reflects a low view of Scripture and a low Christology.

Christocentric and Christotelic Preaching

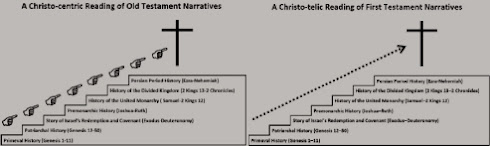

Having summarized how I find Jesus in the First Testament, I need to explain how I understand Christocentric vs. Christotelic interpretation. Unless we get this right, we will not get Christocentric and Christotelic preaching right. Diagrams #1 and #2 in Figure 1 illustrate the difference between a Christocentric and Christotelic interpretation of Scripture.

Figure 1: A Comparison of Christo-centric and Christo-telic Readings

Based on a particular reading of Jesus’ comments to the Emmaus disciples in Luke 24:27 and 44, the Christocentric hermeneutic assumes that all the Scriptures (i.e., every text) speak of him:

Beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he explained to them what was said about himself in all the Scriptures. (Luke 24:27)

Jesus said to them, “This is what I told you while I was still with you: Everything that was written about me in the Torah of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms must be fulfilled.” (Luke 24:44)

These statements undergird the popular statement often attributed to Charles Haddon Spurgeon: when preaching from the First Testament, “I take my text and make a bee-line to the cross.”[6] However, we need to stop attributing this to Spurgeon, since there no evidence that he ever said this.[7] Furthermore, the metaphor itself is absurd, because bees rarely fly in straight lines.[8] Nevertheless, because the metaphor matches Spurgeon’s hermeneutical style, it has encouraged all sorts of illegitimate and foolish typologizing and allegorizing, drowning out the voice of God and obscuring the true message of First Testament texts.[9] The use of Jesus’ statements to defend Christocentric interpretation of all First Testament texts violates the grammar of the Greek. In Luke 24:27 (ἐν πάσαις ταῖς γραφαῖς τὰ περὶ ἑαυτοῦ) the evangelist did not say that all the Scriptures speak of Christ, but that he explained those texts that spoke of him from all the Scriptures. If we recognize Jesus as the embodiment of YHWH, his comments make perfect sense. However, if we interpret this statement with a disciplined Christocentric hermeneutic, the explicitly or implicitly royal messianic texts that Jesus might have had in mind are limited—excluding entire books like Leviticus, Judges, Proverbs, Song of Songs, Esther and Jonah. One wonders what First Testament authors would say about the way we force their writings anachronistically to say all sorts of things that they would not and could not have imagined. And we do this in the name of the divine author of all Scripture.

Applying what we have learned from speech act theory, in terms of locution, I agree that what the human author said the divine author said. However, to many there was no connection between the illocutions (intended meanings) of these two authors. This has led to all sorts of bizarre perlocutions, which typically say more about the interpreters’ ingenuity than the text itself. Through Ezekiel, who received his pronouncements directly from God, YHWH had a word for modern-day charlatans:

“Declare to the self-inspired prophets (וְאָמַרְתָּ לִנְבִיאַי מַלִּבָּם):Hear the message of YHWH! Thus has Adonay YHWH declared: Oy vey[10] to the foolish prophets, who follow their own imagination/impulse (הֹלְכִים אַחַר רוּחָם), and have seen nothing at all!” (Ezek 13:2–3).

It is no wonder that our Jewish friends are upset with us; we have hijacked their Scriptures, and made every text about Christ, often paying no attention to what the divine and human authors originally intended.[11] What then is the solution? Certainly not a repudiation of the messianic witness of the First Testament, nor the rejection of Christ as the one who both fulfills specific messianic prophecies and embodies the fulfillment of the whole promise of the Hebrew Bible. Nor is it found in an exclusively grammatical historical interpretation of each text of Scripture in isolation from other Scriptures. No, the Bible (First and New Testaments) tells a single story of God’s gracious plan of redeeming the cosmos from sin and the effects of the rebellion of those created as his images and commissioned to govern the world on his behalf. That story climaxes in Jesus, whose work is accomplished in two identifiable phases: first, in the incarnation 2000 years ago, when through his death he dealt sin and all the forces of evil a mortal blow, and through the power of his resurrection was exalted as the Son of God. And now we wait for phase two, when he will return and recreate the heavens and the earth in all their original and this time irrevocable perfection and glory. This is the story.

Not every text of Scripture points to Jesus Christ as Messiah, but every text presents a vital part of that story of Jesus, “who is also called the Christ.” We may often grasp the Christological significance of a First Testament text only with hindsight. Some texts introduce the vocabulary that will be necessary for interpreting later events. I have already alluded to the exodus language of Matthew 1:21: “He shall save his people from their sins.” This statement introduces a new notion: salvation from sin. Whereas the First Testament frequently speaks of deliverance (יָשַׁע) from the fury of YHWH, Psalm 130:8 is the only text that associates the root פָּדָה, “to redeem” with sin, as if sin is an enslaving force. Psalm 103:3 speaks of “pardoning” (סָלַח) with reference to (לְ) all your iniquities, which Charles A. Briggs associated with “forgiveness” (סְלִיחָה) in vv. 3–4.12 Psalm 3:9[12] comes close to using exodus language for YHWH’s solution of humans’ sin problem:

Deliver me (הִצִּילַנִי) from all my transgressions (פְּשָׁעַי).

Do not make me the scorn of the fool!

Ezekiel also comes close in two statements that employ the root יָשַׁע, “to save”:

“I will save (הוֹשִׁיעַ) you from all your defilements (טֻמְאוֹתֶיכֶם).” (Ezek 36:29)

“I will save (הוֹשִׁיעַ) them from all their apostasies (מוֹשְׁבֹתֶיהֶם) by which they sinned.” (Ezek 37:23)

Remarkably, although references to “being saved from slavery in Egypt” pervade the First Testament, it never talks about “being saved from sin.” As H. Wheeler Robinson noted long ago, “It [redemption] always marks deliverance from some tangible and visible menace, which may or may not be regarded as a consequence of the suppliant’s sin.”[13] Does Matthew’s application of the exodus verb of salvation (יָשַׁע) for sin mean that the original exodus looked forward to the work of Christ? No, but in the wise and all-knowing providence of God, it provided the vocabulary with which Jesus and the apostles could later interpret the work of Christ.

We could make similar comments about Israel’s sacrificial system. The Pentateuch leaves few if any hints that when Moses or the original Israelites brought their sin offerings they were looking forward to a coming sacrificial Messiah. Isaiah 53 links the revelatory traditions of Messiah and sacrificial offerings for the first time. If anything, the tabernacle and its rituals pointed up, to a heavenly reality (Exod 25:1–9, 40), which we know from the NT to involve the eternal sacrifice of Jesus, slain before the foundation of the world. The author of Hebrews certainly understood the sacrificial system this way. Despite the lack of First Testament evidence for ancient Israelites seeing their sacrifices as pointing to a future earthly event, trusting in the word of YHWH, the faithful knew that if their lives were in order and if they brought their sacrifices with contrite hearts and according to God’s revealed way of forgiveness, they were forgiven (Leviticus 4–6). That is what mattered. Few will have grasped that when the High Priest presented replica sacrifices in a replica sanctuary real forgiveness was theirs because of work of the true sacrificial Savior, who would appear on the scene a millennium later. However, Psalm 32:1 reminds us that real sinners celebrated the grace of real forgiveness.

Before I apply my hermeneutic to Genesis 15:1–6, I must address one additional issue. Sermons have many functions. When we preach evangelistically, we need to follow the paradigm and kerygma of the apostles and preach Jesus Christ crucified and risen again. However, not all sermons serve primarily evangelistic purposes. Preachers proclaim the truths of Scripture to bring about repentance, to reveal God, to encourage and guide believers in a life of godliness, to console those who grieve, and to present hope for the future by effecting transformation in the present. Sometimes the goal of a sermon may be simply to help people read the Scriptures better. Failure to mention Jesus as the sacrifice for our sins and whose resurrection gives us hope in life eternal in a sermon does not mean we have not preached a Christian sermon. When I preach YHWH, I preach the God who was incarnate in Jesus Christ, whether I name him by his NT name or not. What is important for me and for my congregation is that they grasp that every text of Scripture has significance in the light of the climax of the story. This means that rather than reading the Scriptures backwards I read them forwards, interpreting Isaiah in the light of Moses, and Luke and Paul in the light of Moses and Isaiah. If tensions between earlier and later pronouncements arise, I may not force the former to mean what later authors used them for rhetorically, but I must inquire regarding the context of their work how later biblical authors can do with earlier texts what they appear to be doing. Moses does not need to account to Paul, but Paul needs to account to Moses, and if he contradicts Moses, he is the one under the anathema of Deuteronomy 13 (cf. Gal 1:8–9). Later revelation cannot correct, annul, or contradict earlier revelation. God does not speak out of two sides of his mouth. He never needs to say, “Oops! I was wrong. That plan did not work, so I will replace it with a new one.” To resolve the tension, we need to understand the circumstances underlying the NT text and grasp the rhetorical intentions of the author. We make a generic mistake if we imagine Paul and the apostles as seminary students writing exegesis papers on First Testament texts or seminary professors writing theological papers to read at conferences sponsored by the Evangelical Theological Society or the Society of Biblical Literature. They were preachers and pastors eager for transformation in the minds and lives of their hearers through the proclamation of the gospel in all its dimensions and as graciously revealed over time and in history.

Preaching Genesis 15:1–6 Christotelically

There is much more to say on the theory of Christotelic, as opposed to Christocentric reading of Scripture, but part of our assignment for this essay is to show how this might be done with a specific text, Genesis 15:1–6. How might a Christotelic reading of this passage determine the goals of and shape a sermon on this text? Of course, that depends on the function of the sermon. I am sure I could find a way to base an evangelistic sermon on this passage, but for this moment I shall assume the sermon is part of a regular worship service. As I have argued in my book on worship, For the Glory of God: Recovering a Biblical Theology of Worship, I view the regular gathering of God’s people to worship as their response to a gracious invitation to an audience with God. This means that the primary participants are the divine King and believers. In an audience with a superior, by definition, what the superior has to say is always more important that what the subordinates say. This means above all that when I preach, people need to hear me only to the extent that I speak as the mouthpiece of God. Preaching is not about cleverly crafted presentations displaying my rhetorical skills, but about getting out of the way and letting the Scriptures speak, for in the Scriptures we have the only reliable and normative divine word for the people of God.

This means that my goal in preaching Genesis 15:1–6 is not to “make a bee-line for the cross,” unless of course the text sends me there—which it does not—but to stand before this passage with reverence and awe and listen to what God is telling us all about himself, the world, the condition of humanity, and if possible, the world to come. But this calls for clarity in our minds whether we preach a passage, or we preach the message of a passage. Strictly speaking, the former would require we preach the Hebrew text, since of necessity all translation involves interpretation, hence a significant step removed from the original inspired text. However, as I understand it, the latter actually involves expository preaching.

Many Christocentric sermons I have heard are anything but expository. The problem with a Christocentric hermeneutic surfaces early in the history of the church. Here is an excerpt from a sermon on our passage by the fourth century CE preacher Ambrose:

And how did Abraham’s progeny spread? Only through the inheritance he transmitted in virtue of faith. On this basis the faithful are assimilated to heaven, made comparable to the angels, equal to the stars. That is why he said, so will your descendants be. And “Abraham,” the text says, “believed in God.” What exactly did he believe? Prefiguratively that Christ through the incarnation would become his heir. In order that you may know that this was what he believed, the Lord says, “Abraham saw my day and rejoiced.” For this reason, “he reckoned it to him as righteousness,” because he did not seek the rational explanation but believed with great promptness of spirit.[14]

Really? The text offers no hint whatsoever that this was either what Abram was thinking or what the author of this text (human or divine) had in mind. But this hijacking of the Scriptures was of a piece, not only with Ambrose’s virulent anti-Semitism,[15] but later also of Luther’s repugnant disposition toward and treatment of the Jews of his day.[16] On the subject of Christocentric preaching from the First Testament, Luther commented disparagingly:

“Here [in the OT] you will find the swaddling clothes and the manger in which Christ lies, and to which the angel points the shepherds [Luke 2:12]. Simple and lowly are these swaddling clothes, but dear is the treasure, Christ, who lies in them” (Word and Sacrament I, 236).

Next to allegorical exegesis this has been the greatest cause for the veiling of the message of First Testament narratives. Jesus is indeed the telos of the Torah, the hidden treasure, the pearl of great price, but as F. W. Farrar declared 150 years ago,

It is an exegetical fraud to read developed Christian dogmas between the lines of Jewish narratives. It may be morally edifying, but it is historically false to give to Genesis the meaning of the Apocalypse, and to the Song of Songs that of the first epistle of John.[17]

This hermeneutic continues to undermine evangelicals’ credibility in our time: we are dishonest, fraudulent interpreters. We read into a text something it never intended to say. For this reason, the real First Testament has become a dead book and our preaching lacks authority. We have veiled the message of the inspired authors with four or five layers of trivia and speculation. From the perspective of the divine author of Scripture, Jesus Christ is the heart and goal of all revelation (cf. Luke 24:25–35). This is an underlying assumption of Christian exegesis, but it is not the starting point of biblical analysis. How Jesus fits into the message of Genesis 15:1–6 is an important question, but I cannot answer it until I have dealt with the other issues.

In preparing to preach this or any other narrative passage, first I need to attend carefully to how a passage speaks (see Table 1) and then ask what it says about ultimate realities.

Here the narrator paints his portrait of God and Abram with a several different kinds of brush strokes. To grasp his point concerning these characters in the drama I need to pay close attention several features: (1) how the narrator refers to the characters; (2) explicit assessments of the disposition of the characters; (3) his description of the characters’ actions; (3) his recollection of the characters’ speeches; (4) his recollection of what others say about the characters.[18] With reference to God, of these, only (2) is missing in Gen 15:1–6, but it is there with reference to Abram.

The Portrayal of YHWH in Genesis 15:1–6

Table 1: A Discourse/Syntactical Diagram of Genesis 15:1–6

The Narrator’s Designations for God

The patriarchal narratives of Genesis 11:26–35:29 refer to God by several different epithets, each with its own significance: אֱלֹהִים (“God,” 100+), אֵל (El, 15x), עֶלְיוֹן (“Most High,” Gen 14:18, 19, 20, 22), שַׁדַּי (“Shadday,” 17:1; 28:3; 35:11; 43:14; 48:3; 49:25),קֹנֵה שָׁמַיִם וָאָרֶץ (“Creator/Possessor of Heaven and Earth,” 14:19, 22), שֹׁפֵט כָּל־הָאָרֶץ (“the Judge of the whole earth,” Gen 18:25), and of course, יהוה (“YHWH,” 100+). Remarkably, although characters in the narrative will address YHWH as אֲדֹנָי (“Lord, Sovereign”) seven times (15:2, 8; 18:3, 27, 31; 19:18; 20:4), the narrator never does. Here the narrator identifies God only by his personal and covenant name, YHWH, which he does three times (vv. 1, 4, 6). Apparently the patriarchs were not aware of the significance of the name (Exod 6:3). However, through the events associated with the exodus (Exod 6:7; 7:5, 17; 8:22; 10:2; 14:4, 18; 16:12; 29:46; Deut 4:35, 39) and Israel’s experience of divine mercy in the wake of the golden calf affair (Exod 34:6–7), whatever the etymology of the name, their descendants would learn that the name signified “YHWH as Savior” (Exod 2:17; 14:30; Deut 33:29; cf. Exod 20:2; Deut 5:6).19 And with hindsight, this provides the first clue to this text’s Christotelic significance.

The angel’s commentary on the name Jesus in Matthew 1:21 invites Mary and Matthew’s hearers to interpret “Jesus” (יְהוֹשֻׁעַ) as the NT equivalent of the First Testament YHWH, an interpretation that repeated explicit identifications of Jesus with YHWH confirms ( John 1:23; Rom 10:13; 1 Cor 8:6; Phil 2:11). This means that the person who encounters Abram in this text is none other than Jesus, who later in time and space embodied divine glory, grace, and fidelity ( John 1:14, 17).

The Narrator’s Description of Divine Actions

YHWH’s most notable actions here involve communication. Four times the narrator notes that YHWH spoke (אָמַר, vv. 1e, 4b, 5b, 5d). He adds drama to the image by (1) twice using what we refer to as the prophetic “word event formula, “The word of YHWH came to Abram” (אֵלָיו דְבר־יְהוָה/אֶל־אַבְרָם, vv. 1b-c, 4a-b), as if Abram encountered some tangible object; (2) noting that the speech act transpired in visionary form (מַחֲזֶה); and (3) using the optic deictic particle, הֵנִּה, “See, look!” (4a). If we consider the entire chapter, which this episode introduces, this visionary event was extremely complex: Abram was both inside and outside the vision, and God appeared within another revelation of himself (Fig. 2). That YHWH appeared to Abram at all, and that he spoke with him “face to face” is remarkable. But YHWH did more than merely appear or speak. He also took him outside, and given his comment in verse 5, he drew his attention to the heavens.

The conceptual and lexical linkage between the prophetic word event formula and the incarnation, as described by John is striking, though we may debate its precise significance. In the Latter Prophets and elsewhere where Hebrew דָּבָר, “word, declaration, matter, thing, event” occurs, LXX usually rendered the expression as logos. However, the frequency with which the present ῥῆμα appears in the Greek rendering of this formula suggests the alternation is stylistic, depending on the preference of the translator. Conceptually John 1:14 and 17 clearly echo and adapt the formula for new purposes:

The Word (λόγος = דָּבָר) became flesh and dwelt (ἐγένετο = הָיָה) among us, and we have seen his glory (v. 14)

For the Torah was given through (διὰ) Moses; grace and truth happened (ἐγένετο= הָיָה) through Jesus Christ (v. 17).

Going beyond the revelation that Abram received, Jesus Christ represented not merely divine verbal communication, but the embodiment of God, bringing the light of God’s grace to the world ( John 1:1–6).

The narrator concretizes YHWH’s action in relation to Abram by specifying the context: “after these events” (אַחַר הַדְּבָרים הָאֵלֶּה v. 1), that is, after the patriarch’s gallant rescue of Lot from an alliance of Mesopotamian invaders (13:1–16), and his refusal to capitalize on the gratitude of the Canaanite beneficiaries (vv. 21–24). The narrator strengthens the linkage between chapters 14 and 15 with a series of lexical and conceptual allusions: the verb יצא, “to go out,” “to bring out” in hiphil (14:8, 17, 18; 15:4, 5, 7, 14); “possessions” (רְכוּשׁ, 14:11–12, 14, 21; 15:14); the root שׁלם (“king of Salem,” 14:8; שָלֵם, “complete” (15:16); the root צדק, “righteousness” (Melchizedek, “king of righteousness,” 14:18; צְדָקָה , “righteousness,” 15:6); the root מגן (מִגֵּן, “to hand over,” 14:20; מָגֵן, “shield,” 15:1g); the notion of recompense for effort (14:22–24; 15:1h).[20] YHWH’s final action was mental and judicial: he recognized Abram’s faith, and credited his response as “righteousness” (15:6c). I leave a discussion of the meaning of צְדָקָה for later, but for now we observe that YHWH not only observes human actions and is aware of their mental acts, but that he also assesses them properly.

The Narrator’s Recollections of Divine Speech.

As is typical of biblical Hebrew narrative,[21] speeches dominate this text—four by YHWH and two by Abram. The first address is thoroughly ambiguous (v. 1): “Do not be afraid, Abram: I am your shield; your reward will be exceedingly great.” Of what was Abram afraid, that YHWH needed to assure him of his protection? Did he fear the enemies whom he has just defeated will return? Or was he fearful of his own future in an alien land, having been severed from all the bases of security in ancient times: his homeland (אַרצְךָ), his relatives (מוֹלַדְתְּךָ), and his domestic economic unit (בֵּית אָבִיךָ, 12:1).

What sort of reward (שָׂכָר) had YHWH promised Abram? Compensation for the booty that he had just been offered but had rejected (14:21–24)? The opening “after these things” might suggest this. However, Abram’s objection in verse 2 points in a different direction. Abram had stepped out in faith and given up his past because YHWH had promised him a new future, making a great nation of his descendants, and giving him a cosmic mission of blessing (12:2–3), and had later specified that his descendants would possess the entire land of Canaan (12:2; 13:14–17). Presumably the compensation of which YHWH spoke represented the reward for his faith previously demonstrated: land and progeny—nothing more, nothing less.

The questions that YHWH’s ambiguous promise in the first speech had raised the following three speeches answered with crystal clarity (vv. 4c-d, 5c-e, 5g). Rejecting Abram’s proposed solution to his childlessness, with graphic concreteness he answered Abram’s charge that YHWH had failed to give him seed. Although usually translated as “offspring” or “descendants,” we should interpret the word זֶרַע more crassly. Ancient Hebrews considered offspring and descendants as the fruit of the womb (פְּרִי־בָטֶן).[22] In their prescientific world, conception involved implanting male seed (זֶרַע) in the fertile soil of a female’s womb.[23] YHWH’s answer to Abram is graphic and earthy: “one who comes out of your organ” (מִמֵּעֶיךָ אֲשֶׁר יֵצֵא) a euphemism for the penis.[24] However, not only will Abram have a seed (in form יֵצֵא in v. 4d is a collective singular), his progeny will be innumerable like the stars of the sky (v. 5). YHWH’s concluding declaration is colophonic: “This is how your descendants will be” (זַרְעֶךָ כֹּה יִהְיֶה, v. 5g). This heavenly analogy, which will be echoed later (22:17; 26:4; Exod 32:13; Deut 1:10; 10:22; 28:62; 1 Chr 27:23), finds earthly counterparts in “like the dust of the earth” (הָאָרֶץ עֲפַר; 13:16; 28:14), and “like the sand of the sea[shore]” (חוֹל הַיָּם / חוֹל אֲשֶׁר עַל־שְׂפַת הַיָּם and 22:17 respectively).

The Narrator’s Recollection of Another’s Speech.

This issue need not detain us long, for Abram’s comments in verses 2–3 say more about him than about God. On the one hand, he acknowledged YHWH as his [divine] Suzerain (אֲדֹנָי יהוה).[25] On the other hand, he accused him of not having carried out his previous promises. This accusation functions as a thesis statement to the conversation, to which YHWH responded in dramatic form with a counter-thesis, though it is cast as a promise whose fulfillment Abram must await. But what does all this say about YHWH?

First and foremost, YHWH’s comment reminded Abram and reminds us that YHWH is responsive to the anxieties of his people, and as a divine Shepherd, he tries to calm his sheep. He will keep his word. The plan of making Abram a blessing to the entire world depended upon progeny who could scatter to the ends of the earth and thereby serve as agents of blessing. YHWH’s use of the collective “seed” in vv. 4d and 5g suggests the involvement of his descendants as a whole—the fulfillment of which we can see in the incredible contribution Israelites and their successors the Jews have made to the advance of civilization and culture. However, this contrasts with the use of the singular verb and suffix in 22:17c (אֹיְבָיו וְיִרַשׁ זַרְעֲךָ אֵת שַׁעַר), which points to a single person in the future who will fulfill the mandate originally given to Adam and Eve to subdue and rule over the earth, and David’s later recognition of the irrevocable covenant that YHWH made with him and his descendants with “Now this is the Torah of humanity” (וְזֹאת תּוֹרַת הָאָדָם אֲדֹנָי יְהוִה, 2 Sam 7:19). David’s concluding double divine address, “Adonay YHWH!” reinforces this association. Thus, while we may legitimately treat Genesis 22:17 as a Christological text, for this would indeed involve a royal figure, the opposite is true in Genesis 15:1–6. Whereas Abram’s response to his frustration over his childlessness was to name an individual as his heir, the aim of YHWH’s response was to get him to think in terms of an innumerable host of descendants.

The Portrayal of Abram in Genesis 15:1–6

To determine the narrator’s disposition toward Abram we need to ask the same questions we had asked of YHWH.

The Narrator’s Designations for Abram

As the narrator wrote this account, he understood that YHWH would eventually change the name Abram, which means “exalted father,” to Abraham, “father of a multitude”(17:5). Indeed, later tradition would know him only as Abraham.[26] The use of Abram here is obviously significant, for it identifies a man whose faith was immature—he still doubted YHWH’s fidelity to his promise of innumerable progeny—and whose status with YHWH and the world had not yet been formalized through the covenant ritual that followed in verses 7–21, and would be completed thirteen years later in chapter 17.

As was the custom in the ancient world, people of superior rank had the right to change the names of their administrative and social inferiors,[27] and in so doing in effect change their identities. In the Abram-Abraham account, Abram’s change of status would transpire in two stages: YHWH’s official reception of Abram as his covenant partner in 15:7–21, and Abram’s formal acceptance of the role of covenant partner in 17:22–27 and the role of representative of the heavenly court in 17:1 (v. 1, “Walk before me”). To this point YHWH had never spoken of a covenant; Abram had only the verbal promise of divine blessing, which may explain his accusation in 15:3.

The name Abram appears three times here, but only in the first half (vv. 1c, 2a, 3a). The duplication in verses 2a and 3a is odd. Why could the narrator not have cast verses 2b-e and 3b-c as a single speech? Presumably he intended to highlight the intensity of the patriarch’s frustration, a disposition expressed by the deictic particle (וְהִנֵּה/הֵן, “Look!/Now look!”) that introduces the two lines of the second speech (v. 3b-c).[28] As further evidence of the narrator’s strategy, instead of referring to Abram by his name, after verse 3 he only uses the personal pronoun “him” (vv. 4a, 5a, 5f, 6c). This move focuses hearers’ attention away from Abram and onto YHWH.

The Narrator’s Description of Abram’s Actions

The narrator’s portrayal of Abram’s actions in verses 1–6 is extra-ordinary in that the only actions he attributes to the man are speech acts (vv. 2a, 3a), and a mental/dispositional act (v. 6). We will consider the former in a moment, but for now I shall focus on the latter: Abram trusted in YHWH. Although this was obviously not the first time Abram exhibited faith (cf. 12:4), this is the first occurrence of the verb אמן, which in the hiphil stem means “to demonstrate confidence in,” with the object of that confidence (here YHWH) being introduced by בְּ + personal name. The present comment is striking, because it marks a rare example in biblical narrative of the narrator explicitly declaring the disposition of a character. In this account we might have expected YHWH to offer his own assessment.[29]

The Narrator’s Recollection of Abram’s Speech

Having noted that Abram’s principal actions were speech acts, it remains to examine what Abram’s words say about the man. On the surface, Abram’s opening invocation, “O Sovereign YHWH,” appropriately reflects his recognition of his status as the vassal vis-à-vis YHWH. However, in his statements that follow his frustrations with his superior were on transparent display. First, with his rhetorical question, “What can you give me?” he expressed doubt regarding YHWH’s ability to solve the problem of his persistent childlessness.[30] As noted earlier, the question is ambiguous, but the following statement clarifies his issue. The Hebrew וְאָנֹכִי הוֹלֵךְ עֲרִירִי, translates literally, “Now I walk/go childless,” and connotes life as a journey,[31] perhaps even a pilgrimage. However, here the sense is, “By the way, my childlessness persists!” Because Abram had already designated Eliezar, his household steward, as his legal heir, he had obviously assumed the answer to the question, “What can you give me?” that is, “What can you do for me?” to be “Nothing!”

Abram’s second speech was downright accusatory; in exasperation he declared, “Look! You have given not give me seed!” We may assume that in his mind he added “as you promised!” He reiterated emphatically that he had taken matters into his own hands. These are not the words of faith or of righteousness, but the declarations of a doubting and frustrated man.

The Narrator’s Recollection of Another’s Speech

In his verbal responses, YHWH never addressed Abram by name. Instead he immediately addressed his complaint. The first address (v. 4c-d) creates the impression that the patriarch would indeed have progeny to inherit his estate. He rejected Abram’s solution to his childlessness (naming Eliezer as his heir), which reflected a lack of faith, though in that cultural context was perfectly legal. YHWH promised him an heir who would be his physical progeny. Abram probably concluded that YHWH was speaking of a single son, which explains why God later added an object lesson to his rhetoric. After inviting the Patriarch to look up at the heavens and count the stars— which of course is impossible—he declared in three simple words, זַרְעֶךָ כֹּה יִהְיֶה, “This is how your seed will be.”

What do these conversations say about Abram? If Abram’s statements reflect a man with a very deficient faith, YHWH’s reactions function both as a rebuke for his faithlessness and as an answer to his doubts. But YHWH’s speeches offer no hint of how Abram responded. For that we must hear the narrator, who remarkably has the last word on Abram in this short episode.

The Narrator’s Assessment of Abram

The narrator’s assessment of Abram in verse 6 became the foundation for Paul’s watchword in his debates with the Judaizers, and the watchword of the Reformation, particularly in Martin Luther’s debates with the Roman Catholic authorities: “The righteous shall live by faith [as opposed to works]” (Rom 1:17; Gal 3:11; cf. Heb 10:38). However, this statement was not original with Paul, but adapted from the LXX translation of Hab 2:4 (see Table 2).

Table 2: A Synopsis of “The just shall live by faith” Texts

|

Habakkuk 2:4 (MT) |

Habakkuk 2:4(LXX) |

Romans 1:17 |

Galatians 3:11 |

|

וְצַדִּיק בֶּאֱמוּנָתוֹ יִחְיֶה |

ὁ δὲ δίκαιος ἐκ πίστεώς μου ζήσεται |

ὁ δὲ δίκαιος ἐκ πίστεοως ζήσεται |

ὁ δίκαιος ἐκ πίστεως ζήσεται |

|

But the righteous shall live by their faithfulness. |

But the righteous shall live by my faith. |

But the righteous shall live by faith. |

The righteous shall live by faith. |

In addition to recognizing Habakkuk’s modifications of the statement, in assessing later use of earlier texts we must be cautious about imposing alien elements upon the original. While we interpret later texts in the light of earlier texts, we may not force onto earlier texts meanings that were irrelevant to the original situation. Often earlier locutions provided later prophets and apostles convenient verbal instruments for communicating a new and quite different message. However, if we would preach Genesis 15:6, we must preach Genesis 15:6, and not some message that later biblical authors adopted and adapted for quite different polemical purposes. What then does this statement mean?

I begin with the context. The issue in Genesis 15:1–6 is not personal salvation from sin, but the sustainability of YHWH’s plan of redemption and Abram’s role in it. In the end the narrator recognized Abram’s faith in YHWH to fulfill his promise to give him progeny. Because ancient Israelites thought little of “an eternal afterlife,” but perceived themselves as living on in their children,[32] we might think of this as the key to Abram’s eternal life. However, YHWH would not give Abram progeny for Abram’s sake; the point of the divine agenda for the chosen ancestor and his descendants was the removal of the curse from the world and its replacement with the blessing. YHWH’s primary goal here was missional, not personal.

Second, we must assess carefully what “righteousness” (הקָדָצְ) means in this context. In principle, the word and its cognate form קדצ refer not simply to a status or state, but to behavior in accord with an established standard.[33] Correspondingly, a צַדִּיק (“righteous person”) lives according to the established standard (Gen 6:9; 7:1; Deut 32:4 [of YHWH]; Ezek 18:5, 9, 24, 26), as opposed to the רָשָׁע (“wicked person,” Gen 18:23, 25; Ezek 18:20, 21, 23, 24, 27), who does.[34] In the First Testament, the standard is typically the covenant that governs YHWH’s relationship with his vassal Israel, and finds expression in the watchword of Deuteronomy’s covenantal ethic (16:20):

צֶדֶק צֶדֶק תִּרְדֹּף לְמַעַן תִּחְיֶה וְיָרַשְׁתָּ אֶת־הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר־יְהוָה אֱלהֶיךָ נֹתֵךְ

“Righteousness, only righteousness you shall pursue that you may live and possess the land that YHWH your god is giving you.”[35]

Here “righteousness” functions as a comprehensive expression for demonstrated adherence to the covenant in all its dimensions (see Fig. 3)

Deuteronomy 6:25 provides the closest analogue to Gen 15:6 in the First Testament:

וּצְדָקָה תִּהְיֶה־לָּנוּ כִּי־נִשְׁמֹר לַעֲשׂוֹת אֶת־כָּל־הַמִּצְוָה הַזֹּאת

לִפְנֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוָּנוּ׃

And righteousness will be credited to us [lit. “It will be righteousness for us”] if we keep [the covenant] by doing this entire command before YHWH our God, just as he has charged us.

Moses could have recast the first clause in Hebrew by using the verb found in Genesis 15:6:. וְחֲשָׁבָהּ יהוה לָנוּ צְדָקָה, “and YHWH will attribute righteousness to us.” Unlike the assessment of Noah in 6:9 (אִישׁ צַדִּיק ; cf. 2 Sam 4:11), in Genesis 15:6 the narrator has not declared that Abram was righteous or blameless in toto, but that the present act of faith was a righteous act, in the same category as that of the hypothetical creditor who returns the garment that a poor man has given him as security for a loan (Deut 24:13):

הָשֵׁב תָּשִׁיב לוֹ אֶת־הַעֲבוֹט כְּבֹא הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ וְשָׁכַב בְּשַׂלְמָתוֹ וּבֵרֲכֶךָּ וּלְךָ תִּהְיֶה צְדָקָה לִפְנֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ׃

You shall restore to him the pledge as the sun sets, so he may sleep in his cloak and bless you. And it shall be righteousness for you before YHWH your God.

The structure of the final clause differs from Genesis 15:6 but exhibits significant links with the statement in Deuteronomy 6:25:

|

Deut 24:13 |

וּלְךָ תִּהְיֶה צְדָקָה לִפְני יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ |

|

Deut 6:25 |

וּצְדָקָה תִּהְיֶה־לָּנוּ לִפְנֵי יְהוָה אֶלֹהֵינוּ |

|

Gen 15:6 |

וְהֶאֱמִן בַּיהוָה וַיַּחְשְׁבֶהָ לּוֹ צְדָקָה׃ |

Some argue that Abram, who lived ante legem (before the law), and Moses, who lived sub lege (under the law), represented two dramatically different approaches to faith and godliness. According to John Sailhamer, Abraham embodied the divinely approved pattern of a life of faith, while Moses demonstrated the inevitable failure of a life driven by law.[36] However, based upon an analysis of the conceptual and lexical links between the patriarchal narratives and Deuteronomy, in a recent essay I have argued that the author of the former intentionally casts Abraham as the paragon of faith and righteousness as defined by YHWH’s covenant with Israel generally and laid out in detail in Moses’ preaching in Deuteronomy (cf. Gen 26:4–5).[37]

This was not the first and would not be the last time that Abram/Abraham proved his righteousness by faith. Although the word הֶאֱמִין is absent elsewhere in Genesis 12–14, obviously his abandonment of his homeland (12:4–7), at the command of YHWH but without any idea what YHWH meant by “the land that I will show you,” was an act of faith. So was his courage in rescuing Lot and the Canaanites from the Mesopotamian menace, and his refusal to capitalize on another person’s gratitude in chapter 14.

However, the most dramatic moment of faith would come in chapter 22. To Abraham, YHWH’s demand that he sacrifice Isaac must have been preposterous, especially since this episode happened immediately after YHWH had reaffirmed Isaac as the key to Abraham’s future and to the promise (21:12). The narrator casts the event as a test (נִסָּה), but what was YHWH testing? In the event, YHWH declared his verdict on the patriarch’s performance as follows: “Now I know that you fear God, seeing you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me.” (Gen 22:12). As is often the case elsewhere, here “fear” (Hebrew יָרֵא) does not mean fright, but “trusting awe” or “awed trust,” or even “trusting allegiance.”[38] Returning to Genesis 15:1–6, having observed Abram demonstrate faith and in so doing also his righteousness, YHWH could get on with the agenda of covenant ratification, which is what happens in the remainder of the chapter.

Conclusion

How then shall we preach Genesis 15:1–6? I have two responses: First, interpreting this passage within the context of the broader Patriarchal Narratives, we preach the faithfulness of God who is determined to rescue his world from the ravages of sin, and is determined to use human beings—representatives of the Adamic race that is responsible for the problem—to accomplish that agenda. However, the candidates for the privilege all have feet of clay, and when God calls human beings to serve him, he does not transform them into robots (Fig. 5). Instead, he works patiently in them and with them to accomplish his purposes. He neither glosses over human frailties, nor discards in the trash heap of history those whose faith and performance are less than perfect. In his mercy, he calls flawed people, and installs them as agents of the heavenly court.

Second, we preach both the privilege and the burden of being called to serve as agents of the heavenly court. On the one hand, there is no higher honor than to serve in the Creator of heaven and earth’s grand scheme of rescuing the cosmos, and with it the human population, from the effects of sin and the fury of God. But God does not call us according to our gifts; rather he grants us the gifts—even the gift of faith—in accordance with the calling. On the other hand, it is Adonay YHWH, the Sovereign Lord who graciously and sovereignly calls us. We are called to be his vassals, which, as we learn from 17:1, requires us to represent him well, with blameless character and responsible performance of duty. While faith may be discussed as a disposition, it is never perceived in scripture as a mystical quality nor primarily as an interior state. It is a jack-in-the-box that must be demonstrated in action observable to a watching world, and certainly to God.

Where is Christ in all this? I see no hand here pointing to a future eschatological Messiah. On the contrary, this passage obscures the individualized messianic tradition, as it will be played out. YHWH’s earthy description of Abram’s progeny, as “that which issues from your organ,” stands in sharpest contrast to the angel’s announcement to Joseph: “That which has been conceived in her [Mary] is of the Holy Spirit.” To be sure, via the lengthy line of descendants listed in Matthew’s genealogy, Jesus is the climactic seed of Abram, but in the end, amazingly, the last link in this chain does not “issue from” a man’s loins.

And where do we find ourselves in all this? The answer to this question is what excites me about this text. At this moment all Abram had on his mind was physical progeny. But with hindsight we link this text to YHWH’s promise to make Abram and his descendants a blessing on a global scale, and we recognize that we are part of the fulfillment of this promise. Through the seed of Abram the curse has been lifted from us gathered here, and God has lavished on us his blessings not only in heavenly places, but here on earth. But there is more. Paul tells us in Romans 9–11 that I, a Gentile, have been grafted into the tree that represents Abram’s heritage (Rom 9:4–5), which gives me enough reason to exclaim “God blessed forever! Amen?” (v. 5). But I am not only a beneficiary of this heritage. As a child of Abraham by faith I have also been grafted into the Abrahamic and ultimately the Israelite commission—to be an agent of blessing to the world.

In the kind providence of God, four days after I presented an abbreviated version of this paper to the Evangelical Theological Society in Providence, Rhode Island, it pleased God to send me to Hong Kong for a week of ministry, and three days after my return on November 30, I was off to Moscow for a week of ministry in the land of my father’s birth. I was not a tourist on personal self-indulgent vacations (December is not the time to go to Moscow!), but went as a seed of Abraham. In his mercy YHWH had chosen me, not only to be his treasured possession (סְגֻלָּה), but also that just as he had commissioned Israel to do (Exod 19:4–6; Deut 16:19), I might proclaim the excellencies of him who has called us out of darkness into his marvelous light (1 Pet 2:9–10). Hallelujah! What a salvation! And what a Savior!

Notes

- This is an expanded version of a paper presented on November 16, 2017, to the Expository Preaching and Hermeneutics section, chaired by Forrest Weiland, at the annual convention of the Evangelical Theological Society in Providence, RI. The general theme for the session was “Preaching Christ, the Text, or Something Else?”

- 917, according to Bibleworks. Remarkably, in 268 of 566 occurrences of the name in the Gospels, the personal name occurs with the article, ὁ Ἰησοῦς. This occurs elsewhere in the New Testament only in Acts 1:1, 11; 17:3. The significance of the name—to distinguish Jesus, the Christ, from others who bore the name (Joshua, Acts 7:45; Jesus, son of Eliezer, Luke 3:29; Jesus also called Justus, Col 4:11) is evident in the Acts references (though the article in the last one is textually uncertain): (1) “Men of Galilee, why do you stand gazing into heaven? This Jesus (οὗτος ὁ Ἰησοῦς), who was taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven.” (Acts 1:11, ESV); (2) “[Paul explained and proved] that it was necessary for the Christ to suffer and to rise from the dead, and declared, ‘This Jesus ([ὁ] Ἰησοῦς), whom I proclaim to you, is the Christ.’” (Acts 17:3, ESV modified). Unless otherwise identified, all translations of biblical texts in this essay are my own.

- In the Gospels, Christ (χριστός) appears only 54 times, compared to 566 occurrences of Jesus.

- See Daniel I. Block, “My Servant David: Ancient Israel’s Vision of the Messiah,” in Israel’s Messiah in the Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls (ed., R. S. Hess and M. D. Carroll R.; Grand Rapids: Baker, 2003), 17–56; idem, “The Spiritual and Ethical Foundations of Messianic Kingship: Deuteronomy 17:14–20, ” in The Triumph of Grace: Literary and Theological Studies in Deuteronomy and Deuteronomic Themes (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2017), 335–48.

- On Jesus as YHWH in Rom 10:13, see Daniel I. Block, “Who do Commentators say ‘the Lord’ is? The Scandalous Rock of Romans 10:13, ” in On the Writing of New Testament Commentaries: Festschrift for Grant R. Osborne on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday (S. E. Porter and E. J. Schnabel, ed.; Texts and Editions of New Testament Study 8; Leiden: Brill, 2012), 173–92.

- Lewis A. Drummond (Spurgeon: The Prince of Preachers [Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1992], 223) popularized the attribution of this statement to Spurgeon.

- This is acknowledged by Christian George, the curator of the Spurgeon Library at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City. See http://www.spurgeon.org/resource-library/blog-entries/6-quotes-spurgeon-didnt-say.

- Notwithstanding the support for the statement found in a supposedly astute institution, the Gospel Coalition. See Jeramie Rinne @ https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/learning-the-art-of-sermon-application (July 23, 2013). Similarly, R. Albert Mohler, Jr., He Is Not Silent: Preaching in a Postmodern World (Chicago: Moody, 2008), 20–21: “The preaching of the apostles always presented the kerygma—the heart of the gospel. The clear presentation of the gospel must be part of the sermon, no matter the text. As Charles Spurgeon expressed this so eloquently, preach the Word, place it in its canonical context, and “make a bee-line to the cross.”

- Sidney Greidanus’ mere two-page critique of Spurgeon’s method (Preaching Christ from the Old Testament: A Contemporary Hermeneutical Method [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999], 160–162) fails to call out the flaws in his hermeneutic strongly enough.

- Yiddish for אוֹי אֲבוֹי, which occurs only in Prov 23:29: “Who has woe? Who has sorrow? Who has strife? Who has complaints? Who has needless bruises? Who has bloodshot eyes? (NIV).

- For a helpful survey of the effect of this popular but contemptuous Christian hermeneutic on Jewish people and the anti-Semitism it has spawned, see Marvin R. Wilson, Our Father Abram: Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 96–100.

- Charles A. Briggs, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms (International Critical Commentary, 2 vols.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1907), 2.45.

- H. Wheeler Robinson, Redemption and Revelation in the Actuality of History (New York: Harper, 1942), 223),

- On Abraham 1.3.21, as cited by Mark Sheridan, ed., in Genesis 12–50 (Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Old Testament 2; Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2002), 32.

- Responding to Emperor Theodosius the Great’s gracious order that at the bishop’s expense Christians rebuild the synagogue that they had destroyed in Callinicum on the Euphrates, Ambrose responded, “There is, then, no adequate cause for such a commotion, that the people should be so severely punished for the burning of a building, and much less since it is the burning of a synagogue, a home of unbelief, a house of impiety, a receptacle of folly, which God Himself has condemned. For thus we read, where the Lord our God speaks by the mouth of the prophet Jeremiah: “And I will do to this house, which is called by My Name, wherein ye trust, and to the place which I gave to you and to your fathers, as I have done to Shiloh, and I will cast you forth from My sight, as I cast forth your brethren, the whole seed of Ephraim. And do not thou pray for that people, and do not thou ask mercy for them, and do not come near Me on their behalf, for I will not hear thee. Or seest thou not what they do in the cities of Judah?” (Jer 7:14). God forbids intercession to be made for those.” Philip Schaff, ed., Ambrose: Select Works and Letters, Letter XL, accessed November 3, 2017 from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf210.html.

- For an exposure of Luther’s shameful anti-Semitism, see David Nirenberg, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York: Norton, 2013), 246–68.

- F. W. Farrar, History of Interpretation (London: Macmillan, 1886), 334.

- On characterization in biblical narrative, see Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 143–63.

- For thorough and convincing study of the significance of the tetragrammaton, YHWH, see Austin Surls, Making Sense of the Divine Name in the Book of Exodus: From Etymology to Literary Onomastics, BBRSup 17 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2017).

- Cf. Abraham Kuruvilla, A Theological Commentary for Preachers (Eugene, OR: Resource Publications, 2014), 188.

- On the significance of dialogue in biblical narrative, see Alter, Art of Biblical Narrative, 79–110.

- Gen 30:2; Deut 7:13; 28:4, 11, 18, 53; 30:9; Ps 127:3; Isa 13:18; Hos 9:16; Mic 6:7.

- Note the references to semen as שִׁכְבַת־זָרַע, “discharge of seed,” in Lev 15:16, 32; 19:20; 22:4; etc., and to a son as זֶרַע אֲנָשִׁם, “the seed of men,” in 1 Sam 1:11. Genesis 3:15, a poetic text, contains the only reference to the זֶרַע אִשָּׁה, “seed of a woman.”

- HALOT, 609, rightly explains: “that part of the body through which people come into existence.”

- This form of the double address of YHWH occurs elsewhere in the Pentateuch only in v. 8; Deut 3:24; and 9:26, always within an impassioned conversation with YHWH.

- Outside of Gen 11:26–17:5, the name Abram appears only twice in the First Testament, but in both cases the authors note that this was the original name of a man everyone knew as Abraham. The genealogy of 1 Chr 1 names Abraham after Nahor and Terah, but the author adds, “that is Abram” (אַבְרָם הוּא אַבְרָהָם, v. 27). In the poetic ode to YHWH’s faithfulness in Israel’s history in Neh 9:7, the Levites declared, “You are YHWH, the God who chose Abram, and brought him out of Ur of the Chaldeans, and gave him the name Abraham.”

- Cf. Pharaoh’s renaming of Joseph as Zaphenath-paneah in Gen 41:44, the renaming of Daniel and his fellow Jews in Babylon in Dan 1:7, and the reference to Esther, as the alternate name for Hadassah, in Esth 2:7.

- This interpretation is preferable to Kuruvilla’s (Genesis, 189), that YHWH reflected his disapproval “of Abraham’s rather uncomprehending faithlessness.”

- As in 22:12. Similarly, Walter Moberly, “Abraham’s Righteousness (Genesis XV 6),” in Studies in the Pentateuch (VTSup 41; ed., J. A. Emerton; Leiden: Brill, 1990), 103–4.

- Hebrew וְאָנֹכִי הוֹלֵךְ עֲרִירִי (2d) . Compare the Australian question, “How are you going?” which functions as the equivalent for North American, “How are you doing?”

- Thus Bruce K. Waltke, with Cathi J. Fredricks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001), 241.

- Cf. Daniel I. Block, “Marriage and Family in Ancient Israel,” in Marriage and Family in the Biblical World (ed., K. M. Campbell; Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2003), 81–82.

- It is also used in this sense in Imperial Aramaic, as in the eighth century BCE Samalian Aramaic inscription of Panamuwa II (KAI 215), where צדק/צדקה occurs three times (ll. 1, 11, 19) with this meaning. Note especially line 19: “Because of the loyalty [צדק] of my father and because of my loyalty [צדק], my lord [Tiglath-Pileser, king of Assyria] has caused me to reign [on the throne] of my father.” For the translation, see COS, 2:159–60.

- For full development of this behavioral contrast between a righteous man (אִישׁ צַדִּיק) and a wicked man (אִישׁ רָשָׁע), see Ezek 18:3–20. For discussion of this text, see Daniel I. Block, The Book of Ezekiel Chapters 1–24 (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 561–80.

- English translations persistently mistranslate צֶדֶק here as “justice.” Although צֶדֶק/צְדָקָה includes “social justice,” the root צדק is much more comprehensive.

- John Sailhamer, “Appendix B: Compositional Strategies in the Pentateuch,” in Introduction to Old Testament Theology: A Canonical Approach (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1999), 272–89.

- Daniel I. Block, “In the Tradition of Moses: The Conceptual and Stylistic Imprint of Deuteronomy on the Patriarchal Narratives,” in The Triumph of Grace: Literary and Theological Studies in Deuteronomy and Deuteronomic Themes (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2017), 120–22.

- For full discussion of the notion of fear in Deuteronomy and its relation to fear elsewhere, see Daniel I. Block, “The Fear of YHWH: The Theological Tie that Binds Deuteronomy and Proverbs,” in The Triumph of Grace, 283–311; idem, “The Fear of YHWH as Allegiance to YHWH Alone: “The First Principle of Wisdom in Deuteronomy,” in Interpreting the Old Testament Theologically: Essays in Honor of Willem A. VanGemeren (ed., Andrew T. Abernethy; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 150–64.

Unspeakable Crimes: The Abuse of Women in the Book of Judges

By Daniel I. Block

[Daniel I. Block is the John R. Sampey Professor of Old Testament Interpretation at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, where he has taught since 1995. His most recent book is The Book of Ezekiel: Chapters 25–48 in the New International Commentary on the Old Testament.]

Introduction

Few today would deny that the abuse of women has reached epidemic proportions in American society in general and the church in particular. The malady seems to be no respecter of persons, infecting all levels of society, from the courts of the President to the poor ghettoes of our cities and the hollows of Appalachia. As alarming as the scope of the problem is the diversity in its manifestations. The forms of abuse against women chronicled by our newspapers range from psychological violation of innocent young girls to rape and murder of the elderly. While scientific analyses of the problem have been conducted from every conceivable angle, this tide of violence and exploitation has not been stemmed. Explanations for the problem vary, depending upon the discipline in which the research is conducted. For those geneticists who attribute the propensity to commit crimes against women to a fundamental defect in the genes of some males, genetic engineering holds a promise of a cure. Psychologists tend to relate the issue to low self esteem among males, and respond to the crisis by promoting therapy designed to enhance a male’s self-worth. Sociologists see crimes against women by men as natural expressions of fundamentally oppressive patriarchy, and insist that the problems will not be solved until androcentric hierarchical structures are demolished and replaced with truly egalitarian forms.

Since outsiders generally conceive of the church as a major contributor to the problem, it is not surprising that people of the cloth and religious institutions are increasingly marginalized in serious discussions of crimes against women. However, this does not mean that we should be silent. On the contrary, the people of God must seize the initiative in analyzing the social problems of our time and then in proposing solutions that address root causes and not merely symptoms of the malady. This study is offered as a small contribution in the pursuit of this agenda.

I shall begin by examining the biblical book of Judges for evidences and forms of abuse against women in ancient Israel. Then I shall seek to discover the biblical explanation for the problem proposed by this literary document. I am limiting this study to the book of Judges for three reasons. First, although evidence could be drawn from all of the historiographic writings of the Old Testament, space constraints for this article require a severe restriction of the sources and social context to be considered. Second, the book of Judges offers a self-contained composition, deliberate in its literary style and coherent in its theological agenda. Third, the book of Judges presents the contemporary church in North America with the clearest biblical mirror with which to examine itself.

Contrary to prevailing scholarly opinion, the book of Judges was not written primarily to demonstrate the need for a king in Israel in general nor as a defense of the Davidic monarchy in particular. Contrary to prevailing popular opinion, the book of Judges is not about human heroes.[1] Indeed, heroic human figures are rare in the book. We should recognize a clue to the book’s purpose in the Jewish canon, which classifies the writings that make up Joshua to 2 Kings as the former prophets. This book does indeed sound a prophetic cry, exposing the fundamental spiritual problem in Israel and pointing the reader to Yahweh who, by his grace and in keeping with his own purposes for the nation, repeatedly intervenes on Israel’s behalf. Specifically the book describes the Canaanization of Israelite society in the period immediately following the conquest of the land of Canaan after the death of Joshua (Jdg 2:6–3:6).

According to the author of this book, in the centuries between Israel’s arrival in the land and the emergence of kingship the spiritual landscape of Israel came to look increasingly like the landscape of the people whom they had been charged to displace. Evidences of this degeneration may be drawn from many sides. Failure to occupy the land assigned to the respective tribes and failure to eliminate the evidences of Canaanite population and culture speak to Israelite complacency. The hesitancy of some men to assume leadership in Israel (Barak, Gideon) and the promotion by other Israelites of pagan cult forms (Gideon, Micah and his mother, the Danites) indicate a waning dedication to Yahweh. Violence to one’s own countrymen (Gideon) and the exploitation of power for personal advantage (Gideon, Jephthah, and Samson) show the displacement of the divine agenda and the interests of Israel in completely self-centered aims. The assumption of pagan styles of rule (Gideon) and the adoption of pagan forms of negotiating with God (Jephthah, Micah, and the Danites) help blur Israel’s distinctiveness as the chosen people of God. Immoral behavior such as fraternization with the enemy (Samson), thievery and deceit (Micah), disintegration of social mores (the Benjamites), homosexuality and rape (the Benjamites), and intertribal jealousies and war (the Ephraimites) showcase the sinfulness during the period of the judges. In short, the effects of the Canaanization of Israel are evident not only in the religious life of the nation, but especially in its social world, particularly in the way men relate to women.[2]

The book of Judges was not written as an evangelistic tract, calling upon pagans to find life in the God of Israel. It was written to Israel, a nation who claimed to be the people of Yahweh and who demanded that he rescue them in their time of need. By extension the book offers an analysis of a compromised people of God in any age, including the church in America at the end of the twentieth century. Like the Israel of the early Iron Age, many who claim to be the people of God today have been thoroughly Canaanized. Not only has the church taken on features of the pagan world around it, but it also suffers from the same social ills that plague the outside world. Specifically, the differences between the incidence and nature of abuse of women by men inside and outside the church are slight. What then is the answer? Perhaps an analysis of the problem in the book of Judges may point us in the direction we might go.

The Faces of Abuse in Judges

Given the androcentric perspective of biblical writings as a whole, it is no surprise that most of the dominant characters in the book of Judges are male. However, judging by the frequency with which women participate in events, and the nature of their participation, it seems the author of the book was especially concerned about the place of women in ancient Israel.

He mentions by name two Israelite women (Achsah, Deborah) and two non-Israelite women (Jael, a Canaanite; Delilah, a Philistine). The narrator identifies some women by their association with specific men: as wives (Achsah, the wife of Othniel [1:11–15], Deborah, the wife of Lappidoth [4:4], Jael, the wife of Heber [4:17–22], Gideon’s many wives [8:30], Gilead’s wife [11:2], Manoah’s wife [13:2–23], Samson’s wife [14:15–15:6], wives of the 600 Benjamites [21:1–24]); as concubines (Gideon’s concubine [8:31], the Levite’s concubine [19:1–20:6]); as lovers (Delilah [16:4–17]); as mothers (Sisera’s [5:28], Gideon’s [8:19], Abimelech’s [9:1–3; 18], Jepthah’s [11:1–2], Samson’s [13:24–14:16], Micah’s [17:1–3])[3]; as daughters (Caleb’s [1:11–15], Jephthah’s [11:34–40], the Philistines’ in general [14:2], Samson’s Philistine father-in-law’s [14:15; 15:1–6], the man of Bethlehem’s [19:1–9], the old non-Benjamite man of Gibeah’s [19:24], the men of Israel’s [21:1, 7, 18]).

Others are referred to by status (princesses [5:29]), by profession (harlot [11:1–2, 16:1]), by geographic locale (of Timnah [14:1], of Gaza [16:1], in the valley of Sorek [Delilah, 16:4], from Bethlehem [19:1], of Jabesh Gilead [21:12], of Shiloh [21:21–23]), or by their accomplishments (Jael [4:17–22; 5:24–27], a “certain woman” of Thebez [9:53–54]).[4] In several instances the narrator notes simply that a group of people included both men and women (9:49, 51, 16:27; cf. 21:10).

The roles played by these women vary greatly. The most noble figure in the entire book is Deborah, the wife of Lappidoth. She functions as a prophet of Yahweh and is instrumental in the call of Barak to military leadership (4:4–14).[5] In the eyes of the narrator, two others, Jael and the unnamed woman of Thebez, appear as authentic heroines because of their initiative in slaying undesirable characters like Sisera and Abimelech. But none of these women suffers particular abuse at the hands of men. On the contrary, the narrator seems to be amused by the way they subvert traditional male roles in this upside-down period of the judges.

Modern egalitarians may wince at Caleb’s offer of his daughter Achsah as a wife for any man who will capture Kiriath-sepher (Debir). Does her opinion on whose wife she becomes count for nothing? However, the images of Caleb and Othniel portrayed elsewhere in the book and in the Old Testament as a whole are uncompromisingly positive.[6] In fact, Achsah represents a role model of womanly propriety in this patricentric environment. She willingly accedes to her father’s plan, but then demonstrates resourcefulness in convincing Caleb to give her a blessing in the form of a well-watered field in addition to the territory he had given to her husband. While she remains gracious and respectful, in a world of men she will not be merely a passive object of their deals. She seizes the opportunity to achieve something that neither her father nor husband had contemplated, but she does so without overstepping normal and normative bounds of female propriety. At the same time, the men in her life treat her with utmost respect. Indeed their treatment of her presents a sharp contrast to the violence and abuse perpetrated by males against female characters in subsequent chapters. In later narratives the author will exploit the behavior of men toward women to expound his overall theme of the progressive Canaanization of Israelite society in the course of the book. Ironically, perhaps none of the men in this little episode is a native Israelite. They are Kenizzite proselytes[7] who have been so thoroughly integrated into the faith and culture of the nation that Caleb could represent the tribe of Judah in reconnaissance missions, and all three characters model the life of Yahwistic faith in the face of the Canaanite enemy.

Male treatment of women deteriorates precipitously in the course of the book. As the narrator recounts male/female interaction, we have a myriad of examples of the violation and mistreatment of women. Based on the record, one cannot say that Barak abused women, but one can say that he could not accept the possibility of a woman casting a larger shadow than he casts. He does indeed win a decisive victory over Jabin’s Canaanite forces (4:12–13), but only after he has been challenged by the prophetess Deborah not to let the victory fall to a woman (4:9). Indeed he spends the rest of this chapter trying desperately to subvert the prophecy and seize the honor himself. In the end, the fulfillment catches both him and the reader by surprise.

Gideon’s disposition toward women is more problematic. Despite his pseudo-pious utterance to the contrary (8:23), after his victory over the Midianites he adopts the regal style of any ancient extra-Israelite monarch, claiming the bulk of the spoils of war for himself, demanding the symbols and garments of royalty, erecting a national shrine to centralize pagan worship, establishing a harem, and naming one of his sons Abimelech, “[my] father is king” (8:22-3l).[8]

As an institution, the royal harem was fundamentally abusive. Politically, the harem served not only to cement alliances with other rulers, but also to impress them when they came to visit the court. The women in a harem served as ornaments, reflecting the glory and stature of the king. It was even better if they could provide the king with many sons, as was the case with Gideon. Personally, the function of the women who made up the harem was to satisfy the sexual pleasure of the king. In both respects the harem violated the dignity of the women, treating them as mere property to be exploited for the indulgence of the king without respect to their own equally endowed honor as images of God.

As if the establishment of the harem was not enough, Gideon also took a woman of Shechem as his concubine. While many questions concerning the nature of concubinage in Israel remain, concubines were purchased as slaves or claimed as booty in war. Apart from Gideon’s violation of an explicit prohibition on Israelite intermarriage with Canaanites (Dt 7:1–5), the fact that the name of her son is remembered and that he bears a royal name could not hide the indignity she experienced as a second-class wife.