Paul Schmidtbleicher earned a Th.B. from William Tyndale College and Th.M. from Dallas Theological Seminary. Paul pastors Evergreen Baptist Church in the Seattle, Washington area and is on the National Board of Advisors of Chafer Theological Seminary. He has contributed previous articles to the CTS Journal that readers may download from our Internet site: www.chafer.edu/journal. Contact Paul personally at prschmi@attglobal.net.

Introduction

A criticism that has been a thorn in the side of Dispensational Grace Believers has been their relationship to the Old Testament and particularly to the handling of the Old Testament Law. With the resurgence of Reformed and Covenant Theology, these criticisms have become strident. Books challenging Dispensationalism by Curtis Crenshaw, Keith Mathison, and others [1] offer harsh criticisms on many aspects of Dispensationalism including its handling of the Old Testament.

The conflict gap has widened. Charles A. Clough concludes in his article, A Meta-Hermeneutical Comparison of Covenant and Dispensational Theologies that,

The conflict between the two theologies could only be lessened if Covenant Theology would attend to the integrity of the biblical covenants and if Dispensational Theology could convince its critics that it sees only one way of salvation and that it listens to all Scripture whether directly addressed to the Church or not. Meeting either requirement in the near future is unlikely. [2]For many Dispensationalists, the issue of salvation is clear in that there is only one way of salvation that is “faith in Christ.” Whether we look back on His historical Person and Work as New Testament saints or looked forward to the promised and foreshadowed Savior as did the Old Testament saint, it is faith in Christ that enters one into eternal salvation. As … he [Abram] believed in the Lord (Genesis 15:6), so we have obeyed, believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and you will be saved (Acts 16:31) and received eternal salvation. [3]

The important comment from Clough for this study involves how we “listen to all Scripture.” Other believers outside of the Dispensational camp picture Dispensationalists as dividing the Bible—dividing it to such an extent that they pick and choose what may or may not apply, ending with a “buffet” selection of principles. Some Dispensationalists, on the other hand, discount solid guidance and principles because they come from the Old Testament that (as often taught) the New Testament supplanted.

For example, the issue of capital punishment divides Christians primarily because of the division of the Testaments. The New Testament alludes to it in passages like Romans 1:32 where certain people are worthy of death, while the Old Testament clearly upholds it beginning in Genesis 9:6: Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man his blood shall be shed; for in the image of God he made man. Those persons strictly dividing between Old and New Testaments would generally hold that the New Testament has done away with the Old Testament and thus have a very weak view, if any, on capital punishment.

I became aware of these practical problems in “listening to all Scripture” during the era of the Vietnam War as one of the pastors held to a solid dispensational theology yet developed an excellent Doctrine of War [4] from scriptures derived primarily from the Old Testament. My question was, “What determines our use of the Old Testament?” Certainly it has to be a more solid principle than “pick and choose” as we wish.

A second example would be in the area of teaching on finances. Many believers find themselves in deep trouble when it comes to finances. The primary verse of the New Testament used for financial counsel is Romans 13:8, Owe no one anything. In a New-Testament-only understanding of finances, one cannot be in debt. Yet, in the purchasing of a house and car, most believers blatantly violate this verse as commonly interpreted. Knowingly violating one verse, because almost everybody “has to do it,” lends itself to the view that believers can “fudge” a bit on God’s commands. One can foresee a gradual slide in the wrong direction. On the other hand, the Old Testament Law has a set of highly developed economic principles to offer if we “listen to all Scripture.” The question again arises, “On what basis do we make use of the Old Testament?” This article is an attempt to answer these questions.

The Mosaic Law and God’s Moral Law

The Law of Moses appears in Scripture to have three divisions. The Westminster Confession of Faith states these three divisions as follows:

WCF 19.3 Besides this law, commonly called moral, God was pleased to give to the people of Israel, as a church under age, ceremonial laws, containing several typical ordinances; partly of worship, prefiguring Christ, His graces, actions, sufferings, and benefits; and partly of divers instructions of moral duties. All which ceremonial laws are now abrogated under the new testament.

WCF 19.4 To them also, as a body politic, He gave sundry judicial laws, which expired together with the state of that people, not obliging any other now, further than the general equity thereof may require. [italics mine]. [5]I believe the division is helpful for classifying various parts of God’s Law to Moses. Still, in dividing the Law of Moses, the Westminster Confession did, as others who followed, divide portions of the Law believed to be fulfilled from portions still believed to be in effect. Many believe that the “ceremonial laws” and also the “judicial laws” are either abrogated by the New Testament or ended with the Old Testament state of Israel. Many also believe that the “moral laws” of the Mosaic Law have continued and are still binding in the New Testament.

It is against such a dividing of the Mosaic Law and the continuing authority of a portion of it that many Dispensationalists argue. Alva J. McClain put the controversy into perspective several years ago when he said,

Various motives, some good and some bad, have led men to raise the issue. In recent years it has been raised by some good men with the best of intentions. They have been deeply grieved and disturbed by the failure of Christian people to live as those saved by grace should live. As a remedy for this distressing situation they have proposed that we should turn back to the law. We have failed, they argue, because the obligations of the “moral law” of God have not been laid upon consciences of the saved. The path of success in the Christian life, they say, will be found in getting the people to recognize that they are still under the moral law. [6]In a series of points, McClain argues in his second point that the Law of Moses is a unified whole and cannot be divided up to say that some of it is still relevant and some is abrogated by the New Testament. McClain says,

2. This law is one law an indivisible unity. While it is unquestionably true that at least three elements appear within this one law - moral, ceremonial, and civil - it is wrong to divide it into three laws, or as is popularly done, divide it into two laws, the one moral and the other ceremonial.

This is clear from the New Testament references. James declares that “whosoever shall keep the whole law, and yet offend in one point, he is guilty of all” (2:10) ….

The same viewpoint is expressed by the Apostle Paul in Galatians 5:3, “For I testify again to every man that is circumcised, that he is a debtor to do the whole law.” And Christ declares that “whosoever therefore shall break one of the commandments, and shall teach men so, he shall be called the least in the kingdom of heaven” (Matt 5:19), thus upholding the essential unity of the law. That the “least commandments” referred to by our Lord are those set forth in the Pentateuch, and not merely those of the “moral law” or the few contained in the Sermon on the Mount, is perfectly clear from the context in verses 17 and 18, where the identification is unmistakable. He is speaking about the law of Moses. [7]While some divide the Mosaic Law into those portions abrogated and a “moral law” that still applies, Sumner Osborne goes a step further to try to discount the existence of any “moral law” outside the Law of Moses.

From Adam to Moses we are told there was no law (Rom 5:13), and therefore the sins of men did not have the distinct character of transgression in God’s dealings with them. After the law was given, only the nation Israel was under it. The Gentiles were still without law and perish without it, in contrast to the Jews who were under it and will be judged by it (Rom 2:12). Conscience is a sort of law to the Gentiles, for it accuses when they do wrong somewhat as the law does those who are under it; but it is clearly stated that they did not have any actual law. Some have thought that Romans 2:15 proves that Gentiles were under what they call “the moral law” after all, for it speaks of “the work of the law written in their hearts.” But we must carefully note that it is not the law that they have written in their hearts, which would be the same as our blessing under the new covenant (Heb 10:16), but the work of the law written there. If a Gentile gathered somehow that he ought to honor his parents, even though he had never heard of the law, this particular work enjoined by the law would be a law to him and accuse him if he did not. This in no way proves, however, that Gentiles were under the law.

To repeat, when Scripture speaks of “the law” it is referring to this administered code given through Moses at Sinai, and not to some other law above and beyond it which has always been in effect and always will be, called “the moral law.” It is claimed that this supposed moral law is a transcript or reflection of the character of God and is therefore eternal. As to this the Scriptures are silent, for they neither mention such a law nor describe it. [8]To summarize, those on the Westminster Confession side of the question regarding the use of the Old Testament and its law believe that Jesus Christ and the New Testament abrogated only a portion of the Law of Moses, namely the ceremonial laws and the judicial or civil laws. They hold that the Ten Commandments are God’s “Moral Law” that is still in effect. Therefore, the New Testament Christian would still be under this portion of the Mosaic Law.

On the other hand, the Dispensationalist sees the Law of Moses as a unified law system even though one may subdivide it into three separate law categories. The whole unified Law of Moses was set aside by the Work of Christ in the New Testament—the New Testament abrogates all the Law of Moses. For some, like Sumner Osborne, there is no separate “moral law,” even for the Gentiles.

My position is that it can be shown from Scripture that there is such a thing as an eternal law of God from which the patriarchs functioned, from which God gave the written Mosaic Law Covenant, the New Testament Laws, and from which God will establish the millennial kingdom laws. If one argues for taking a division of the Mosaic Law called the “moral law” and seeks to impose it on the Gentiles, or to continue it as a part of the Mosaic Law on the New Testament saint, then they are in error. Yet, if one considers all Scripture, God’s Eternal Law surpasses the Law of Moses and has been in effect since the beginning. To differentiate from the arguments over the “moral code” of the Law of Moses, this article will not call this “The Law” nor “Law” nor even “Eternal Law,” but will call this God’s Eternal Law.

The Existence of God’s Eternal Law

Prior to the giving of the law to Moses, there is clear evidence that God had established laws by which mankind was to live. Although some aspects of God’s Laws changed, they show in Scripture. The following provides a partial list of indications of God having established law prior to the Law of Moses.

In the Garden—In the garden, man had legal instruction on the sacrifices the Lord found acceptable.

Abel also brought of the firstborn of his flock and of their fat. And the LORD respected Abel and his offering (Genesis 4:4).

By faith Abel offered to God a more excellent sacrifice than Cain, through which he obtained witness that he was righteous, God testifying of his gifts; and through it he being dead still speaks (Hebrews 11:4).At the Boarding of the Ark—Noah would board the animals on the Ark two by two for all the “unclean” animals and would board three pair plus one (7) of the clean animals long before God gave the written law on clean and unclean animals in Leviticus 11.

And of every living thing of all flesh you shall bring two of every sort into the ark, to keep them alive with you; they shall be male and female (Genesis 6:19).

You shall take with you seven each of every clean animal, a male and his female; two each of animals that are unclean, a male and his female (Genesis 7:2).At the Time of Abraham—Law of the Tithe. Abraham knew the minimum requirements of the Lord in his paying the tithe to Melchisedek, King of Salem.

And blessed be God Most High, who has delivered your enemies into your hand. And he gave him a tithe of all (Genesis 14:20).Specifically with Abraham. God told Isaac at the time of the renewal of the Abrahamic Covenant that his father Abraham had obeyed the Lord and kept the Lord’s commandments, statutes, and laws long before God gave the Mosaic Law.

Because Abraham obeyed My voice and kept My charge, My commandments, My statutes, and My laws (Genesis 26:5).At the time of the Exodus from Egypt. Prior to the nation of Israel’s coming to Mount Sinai to receive the written Law of Moses, God had them under a system of Law referenced in Exodus.

Then the LORD said to Moses, “Behold, I will rain bread from heaven for you. And the people shall go out and gather a certain quota every day, that I may test them, whether they will walk in My law or not” (Exodus 16:4).

And the LORD said to Moses, “How long do you refuse to keep My commandments and My laws” (Exodus 16:28)?Thus, from the cited passages there emerges the Biblical principle of the laws of God being in existence prior to the giving of the Law of Moses. Alva J. McClain also speaks of these indications of God’s Law existing prior to the written Mosaic Law. In his sixth point on “What is The Law,” McClain sets forth the fact that God’s Laws existed prior to Sinai as God revealed them and men carried them on by word of mouth.

6. This written Mosaic law points back to a prior divine law of which the Mosaic law in part is an amplification recorded by divine inspiration. That there was divine law prior to Sinai there can be no serious question. The proof is twofold: First, the written Mosaic law itself testifies to the existence of an earlier law. See the law of Eden (Gen 2:15–17); the law of sacrifice (Gen 4:4 with Heb 11:4); the law of tithes (Gen 14:20); the law of circumcision (Gen 17:10–14); etc. Second, we have the testimony of archaeological records which contain clear evidence of law before Moses. For example, the Hammurabi Code probably existed as early as 2100 B.C. and contains some striking resemblances to the Mosaic Code.

The Bible mentions two possible sources for such law before Moses: First, the Book of Genesis records many instances of God speaking to men in direct and original revelation of his will (cf. Adam, Noah, Abraham, etc.). Second, the Apostle Paul in Romans 2:14–15 refers very clearly to a law divinely implanted in the very constitution of man by creation. [9]Therefore, a form of God’s Law existed in the era before Moses. It certainly existed in the Mosaic era of the nation of Israel. In the age of the Church, the New Testament repeats all ten commandments in one form or another. To this truth, Roy L. Aldrich, founder and first president of Detroit Bible College attests when He says,

… none of the ten commandments reappear in the New Testament for this age of grace as Mosaic legislation. All the moral principles of the ten laws do reappear in the New Testament in a framework of grace. The Christian is not under ‘the ministration of death, written and engraven in stones,’ but he is under all the moral principles on those stones restated for this economy of grace. He is under the eternal moral law of God which demands far more than the ten commandments. It calls for nothing less than conformity to the character of God. This is as far from antinominianism as heaven is far above the earth. [10]A brief chart of all ten commands and their New Testament counterparts shows the connection of New Testament commands with the Eternal Law of God. Even the Sabbath command, generally left out by some, shows that we should not only set aside one day in seven as a reminder of the grace of God, but that we are to celebrate His graces daily.

The Old Testament’s 10 Commandments

|

Content of the Commandments

|

New Testament Counterparts

|

Command 1: Deuteronomy 5:7

|

Only one God

|

Acts 14:15; 1 Cor. 8:6; 1 Timothy 2:5; James 2:19

|

Command 2: Deuteronomy 5:8–10

|

No other gods

|

Acts 15:29; 1 Cor. 8:1–10; 2 Cor. 6:16–17; 1 Jn. 5:20

|

Command 3: Deuteronomy 5:11

|

No on Lord’s Name in Vain

|

Matthew 5:33–37; James 5:12

|

Command 4: Deuteronomy 5:12–15

|

One day in seven

|

Romans 14:5–6; Colossians 2:16–17

|

Command 5: Deuteronomy 5:16

|

Respect parents

|

Matthew 15:3–4; Ephesians 6:1–3

|

Command 6: Deuteronomy 5:17

|

No premeditated murder

|

|

Command 7: Deuteronomy 5:18

|

No adultery

|

Matthew 5:27–28; 1 Cor. 6:18–20

|

Command 8: Deuteronomy 5:19

|

No stealing

|

Ephesians 4:28

|

Command 9: Deuteronomy 5:20

|

No false witness

|

Colossians 3:9–10

|

Command 10: Deuteronomy 5:21

|

No coveting

|

Ephesians 5:3

|

The similarity of these New Testament commands with their Old Testament counterparts does not mean that God imposes the External Mosaic system of Law in the New Testament. However, there exists an Eternal Law of God from which God commanded the Patriarchs, from which God gave the Mosaic Law Covenant, and from which God based the New Testament Commands.

The Millennial Age upon the earth also shall be governed by laws that the Lord will draw from the Eternal Laws of God. The Messianic prophecies of Revelation 12:5 and 19:15 speak of the Lord Jesus Christ ruling with a rod of iron. Generally, godly rule, as seen in the Scriptures, is established by law. With this example, we can project that there will be law in the Millennium and it will be based in the Eternal Law of God.

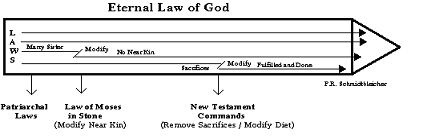

To summarize, the existence of law prior to the Law of Moses that is similar in many ways to the Law of Moses; the actual Covenant of Law given to Moses, and the similarity of New Testament commands to the Old Testament Law of Moses all point to an Eternal Law of God from which each era draws its laws. Note the following diagram.

The Agreement between Different Eras of Law and Current Thought

In some specific laws given before Moses, there is full agreement with the written law as it was revealed to Moses. Such examples of animal sacrifices, clean and unclean animals, circumcision, and the practice of the tithe were not changed, but put in written form in the Law of Moses. This shows a general agreement between the laws in effect before Moses and the Law of Moses.

In a similar fashion, the restatement of the Ten Commandments in the New Testament shows a general agreement between the New Testament commands and the Ten Commandments classified as the “moral code” of the Law of Moses. One result of this for those upholding the Westminster Confession has been to make the choice for a portion of the Law of Moses to be still in effect and binding. They see the “moral law” (The Ten Commandments), as continuing in its external fashion, imposed on the New Testament believer.

The clear teaching of the New Testament is rather an abrogating of the whole Mosaic system and an establishing of a new system based in the same Eternal Law of God. Here is where the Westminster versus Dispensational theological battles over the Law are fought. The Westminster followers overemphasize the New Testament saint being under a portion of the external law system of Moses and the Dispensationalist often overemphasizes a disregard for any of the laws found in the Old Testament Law of Moses.

As far as taking sides, the author stands in the Dispensationalist camp of belief that the Law of Moses as an external system is superseded by the New Testament and the ramifications of the Cross of Christ. Dr. Robert P. Lightner sums up the dispensational view on the Law of Moses when he says, “Dispensationalists believe the Law of Moses in its entirety has been done away as a rule of life. This strikes at the very heart of theonomy in particular and of covenant Reformed theology in general.” [11] Dr. Lightner uses six passages of Scripture to show that the external system of the Mosaic Law has been done away as a rule of life. I shall briefly summarize Dr. Lightner’s points on each passage.

- Acts 15:1–29—The Law of Moses is an external “yoke” on the neck of the Old Testament saint and would not be imposed on the New Testament Church age believers.

- Galatians 3:17–25—The argument here is that the external written Law of Moses was a temporary “schoolmaster” to protect and lead unto the coming of Christ.

- Galatians 5:18—But if you are led by the Spirit, you are not under the law. The position of the New Testament believer being under the leading of God’s Holy Spirit separates the believer out from being under the Law of Moses.

- Romans 6:14— … for you are not under the law but under grace. Because of our being identified with Christ in His death and resurrection, a new position gives the believer daily deliverance from the bondage of sin. The context emphasizes a deliverance that works: we are not under the Law experiencing failure due to inclusion of the flesh (Romans 8:2), but under grace experiencing victory due to a new dependence on the Lord.

- 2 Corinthians 3:6–13—The Law of Moses, engraven in stones, was a ministration of death and glorious in its day. Three times scripture says the Law is fading (3:7, 11, 13), and being replaced by the far more glorious ministry of the Spirit.

- Hebrews 7:11–12—Christ’s priesthood is superior to the Levitical priesthood. Since the Law and the Levitical priesthood are inseparable, Christ has done away with the external Law of Moses as He has done away with the Levitical priesthood. [12]

Balancing the Use of the Old Testament and Its Law

If the reader accepts the premise outlined so far—namely that there is an Eternal Law of God (not limited to the “moral law” of Moses) from which has come law for the Patriarchs, the complete system of law under Moses, the commands stated in the New Testament, and probably the laws to be instituted in the Millennium—then the next step is understanding how they fit together. Herein the issues of continuity and discontinuity between the testaments becomes involved. [13]

The thought that has developed historically how the Old Testament and New Testament might fit together when it comes to “law” runs from absolutely no use of the law to a use that is completely binding. David Dorsey, associate professor of Old Testament at the Evangelical School of Theology in Myerstown, Pennsylvania, has set forth his perspective on the continuity and application of the Law. His listing below summarizes from the least continuity and use of law to the most:

- Marcion—Marcion, the gnostic heretic of the second century, completely threw out the Old Testament with its law seeing it as inferior to Christ and Christianity.

- Dispensationalism—The hermeneutic that holds that God developed different programs for different ages relegates the Old Testament and its law to Israel and in no way applies to the New Testament Christian.

- Covenant Theology—Reformed theologians see a greater continuity between the testaments. The Church is spiritual Israel and the “moral laws” (Ten Commands minus the fourth) given to Israel are also laws for the Church.

- Seventh Day Adventism—Adventists stand with Covenant Theology, but also see the fourth commandment or Sabbath as binding, together with the dietary regulations.

- Christian Reconstruction—A spin-off from Reformed Theology, Reconstructionism argues for the continuity of all the commands including the “judicial laws.” Only the ceremonial laws were fulfilled in Christ and abrogated.

- World-Wide Church of God (former cult)—This theology argues for even more continuity and disregards only a few laws as no longer valid like sacrificial regulations. [14]

Modifying Our View of the Old Testament and Its Use

Many who would fall under dispensational theology also rigorously proclaim “the tithe” when it comes to giving. Congregation members regularly speak of giving their tithe. Theologically, the dispensational theology of these churches, to be consistent, would dictate that the tithe as part of the Law of Moses is no longer in effect. Of course few will do this, nor should they, if they would adopt a more balanced view of using the Old Testament. The same could be said for what should be done by way of national defense. The New Testament by itself gives little if any directives on national defense. Can the Dispensationalist make a case from the Old Testament and still be dispensational? The answer lies in defining the New Covenant as it applies to the Church and the specifics of how teaching “all Scripture” writes the Eternal Law of God upon the hearts of the saints.

The New Covenant

The New Covenant given specifically to Israel originally spawned three premillennial views. Dr. Dwight Pentecost outlined these three views in his book, Things to Come. The views are listed by their Premillennial proponents:

- Darby View—The New Covenant is strictly for Judah and Israel with no Church-age involvement at all.

- Chafer, Walvoord, Ryrie View—There are two new covenants. One new covenant is strictly for Israel with its provisions and the other new covenant (mentioned, but practically undefined in the New Testament) is for the Church.

- Scofield View—One New Covenant to be fulfilled in detail for Israel in the future and now applied to the Church during our current dispensation. [15]

A new setting for the stalemate over law and grace is now possible because of the dramatic change effected around 1965. It was about that time that Dispensationalists decided that no longer would they hold to two new covenants, one for the Church and one for Israel. Even though Jer 31:31 clearly affirmed that God had directed the “new covenant” to “the house of Israel and … the house of Judah,” it was now seen that the Church was also involved. [16]Furthermore, Bible scholars suggest that the teachings of law under the New Covenant comes from the Law of Moses. Walter Kaiser and Bruce Waltke seem together on this point:

The identical point has also been raised recently by Bruce Waltke. While commenting on the phenomenon of conditionality within the unconditional covenants, he affirms that “Jeremiah unmistakably shows [the new covenant’s] continuity with the provisions of the old law.” With respect to the promise of God in the new covenant that he would “put [his] law in their minds” (Jer 31:33), Waltke correctly asserts that “the law in view here is unquestionably the Mosaic treaty. It is summarized by the expression ‘Know YHWH.’ In short, the new covenant assumes the content of the old Mosaic treaty.” [17]Under the Scofield or one covenant view, the New Covenant contains both physical and spiritual blessings. It was specifically given to Israel and will ultimately be fulfilled by Israel as they receive both the physical and spiritual blessings. The Church participates spiritually by enjoying the spiritual blessings of the covenant. To this point Messianic Jewish scholar Arnold Fruchtenbaum says:

Like the Abrahamic, the one New Covenant is made with Israel. Like the Abrahamic, the one New Covenant contains both physical and spiritual blessings. As with the Abrahamic, the physical promises are limited to Jews only but the spiritual blessings were to extend to the Gentiles. What the Church is now enjoying are the spiritual blessings of the Abrahamic and New Covenants. [18]The Scriptures affirm the Church age believer to be intricately involved in the New Covenant. This in no way limits its ultimate and complete fulfillment with Israel. The Lord Jesus Christ in the institution of the Lord’s Table introduced the New Covenant (Matthew 26:28; Mark 14:24; Luke 22:20). The Apostle Paul calls himself a minister of the New Covenant in 2 Corinthians 3:6. And the author of Hebrews pictures the Church as being under a new and better covenant (Hebrews 7:22; 8:6; 9:15, etc.)

Under the New Covenant, the spiritual blessings enjoyed by the Church include (1) Sins forgiven; (2) Personal relationship with God; (3) The indwelling of God’s Holy Spirit; and (4) The internalization of the Word and Laws of God.

It is the internalization of the Word of God and the Laws of God that becomes the focus of modifying our view of the Old Testament and its use. The Law of Moses was an external system that could not accomplish life because of its reliance upon the flesh.

For what the law could not do in that it was weak through the flesh, God did by sending His own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, on account of sin: He condemned sin in the flesh (Romans 8:3).There was nothing wrong with the Law (Moses) except that it was dependent upon the flesh that was weak.

Is the law then against the promises of God? Certainly not! For if there had been a law given which could have given life, truly righteousness would have been by the law (Galatians 3:21).Therefore the Lord took the participation of the flesh away and replaced the external Law of Moses with a system dependent upon the Holy Spirit and a growing internalization of His Word, including Law, that would mold the responsive hearts given to us as another spiritual blessing of the New Covenant.

For I delight in the law of God according to the inward man (Romans 7:22).Is the Law of Moses included in this internalization? Reason exists for believing that it is. After all, the New Testament has only good to say about the standards and principles of the Law of Moses with the exception that it was weak because of man’s participation and could not give life. The following passages show the attitude of the New Testament toward the Law of Moses.

Do we then make void the law through faith? Certainly not! On the contrary, we establish the law (Romans 3:31).

Therefore the law is holy, and the commandment holy and just and good (Romans 7:12).

If, then, I do what I will not to do, I agree with the law that it is good (Romans 7:16).

But we know that the law is good if one uses it lawfully (1 Timothy 1:8).Furthermore, the New Testament Scriptures themselves proclaim that the whole of them, Old and New Testament, are the content of preaching and teaching. Consider the following Scripture passages that uphold the value of the Old Testament and its Law to the New Testament saint beginning with a most important passage:

All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, thoroughly equipped for every good work (2 Timothy 3:16–17).

For whatever things were written before were written for our learning, that we through the patience and comfort of the Scriptures might have hope (Romans 15:4).

Now these things became our examples, to the intent that we should not lust after evil things as they also lusted (1 Corinthians 10:6).

Now all these things happened to them as examples, and they were written for our admonition, on whom the ends of the ages have come (1 Corinthians 10:11).Of course one of the most important passages that upholds the value of teaching and preaching all scripture is 2 Timothy 3:16–17. This includes the history, poetry, and laws of the Old Testament. When teaching the Law of Moses to a New Testament saint it is not taught to be an external system to be imposed as the “yoke” of Moses, but as an example of the very “mind of Christ” (1 Corinthians 2:16) as God and as part of the Eternal Law of God. In the New Testament (Covenant) era, it is the ministry of the Holy Spirit to internalize the teaching of the whole of God’s Word, writing it upon our hearts.

The function of the Christian way of life then is not obedience to an external system (Mosaic Law) of law, but to be (1) walking in the Spirit (2) having put on the New Man renewed in knowledge (Colossians 3:10) from the whole of Scripture. Under such a scenario, the Spirit and the Word of God in the heart (from all Scripture), not the letter of the law becomes the standard in keeping with Romans 7:6 and 2 Corinthians 3:6.

But now we have been delivered from the law, having died to what we were held by, so that we should serve in the newness of the Spirit and not in the oldness of the letter (Romans 7:6).

Who also made us sufficient as ministers of the new covenant, not of the letter but of the Spirit; for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life (2 Corinthians 3:6).On the other hand, if preachers do not teach the whole of Scripture, the New Testament believer is limited in his “inner man” concerning the Eternal Standards and Law of God. Under this scenario, it is easy to see where division arises over subjects such as war, capital punishment, debt, etc. In these areas the mind of Christ (1 Corinthians 2:16) presents itself primarily in the Old Testament as incorporated into parts of the Law of Moses. By

practically “throwing out,” these portions of Scripture, the Believer is without Divine guidance in these areas.

Does all the Old Testament Apply?

There are similarities in each era or dispensation that seemingly shows continuity in the Eternal Law of God. Yet, there are also a number of changes. One change made between the Patriarch period and the Law of Moses period would be the laws on marriages of near kin. It is obvious that under the Patriarch Law that Seth and Cain married sisters as they had families and progeny. With the Law of Moses, Leviticus 18 spelled out the change on prohibitions on marrying near kin.

One also sees clear changes between the Old and New Testament periods. Two examples would be:

(1)The Sacrificial System—The Law of Moses had a complete system of ordinances for the sacrifices and offerings. The book of Hebrews explains that the sacrificial system was a foreshadowing of the real sacrifice of Jesus Christ. Since He has come and once for all offered Himself as the Perfect Sacrifice for sin, the shadow system is now superseded (Hebrews 8–10).

(2) The Regulations on Diet—The Law of Moses sets forth in Leviticus 11 a complete set of dietary regulations that govern what those under the Law of Moses could and could not eat. In the New Testament the Lord approaches Peter in a vision of many unclean animals and commands him to eat what God has now cleansed (Acts 10:11–16). Furthermore, Paul writes this change under divine revelation into Colossians 2:16.

So let no one judge you in food or in drink, or regarding a festival or a new moon or Sabbaths (Colossians 2:16).The obvious conclusion is continuity in God’s Eternal Law—the law that succeeding ages would draw upon. The law would continue, possibly in a different approach, unless the later law, revealed at a later time, superseded and modified the earlier law.

Therefore, if one were to preach on the Old Testament Tabernacle and sacrificial system, the superseding revelation in Hebrews also should be preached showing the end of that system. On the other hand, preaching about criminal law from the Old Testament stands as the New Testament has not modified (to my knowledge) how a nation entrusted with human government is to deal with its criminals.

The Extent of Teaching the Old Testament

In studying the Law of Moses, there is a true threefold division as spelled out in the Westminster Confession: Moral Law (Ten Commandments), Ordinances (Sacrificial System), and Judgments (Judicial Laws). Though the Reconstructionists, formerly headed by R.J. Rushdoony, wrongly see the Law of Moses continuing as a system and as the way of sanctification, [19] they have done much work in relating the Ten Commandments (Moral Law) to their respective case laws (Judicial Laws). Rushdoony says,

… First, certain broad premises or principles are declared. These are declarations of basic law. The Ten Commandments give us such declarations. The Ten Commandments are not therefore laws among laws, but are the basic laws of which the various laws are specific examples… .With this in mind, that the law, first, lays down broad and basic principles, let us examine a second characteristic of Biblical law, namely, that the major portion of the law is case law, i.e., the illustration of the basic principle in terms of specific cases. These specific cases are often illustrations of the extent of the application of the law; that is, by citing a minimal type of case, the necessary jurisdictions of the law are revealed. [20]Rushdoony continues to illustrate this concept by citing:

- Basic law declaration: Thou shalt not steal (Exodus 20:15)

- Illustrative case law: Don’t muzzle the ox treading the corn (Deuteronomy 25:4)

- Paul’s application of the Old Testament on proper payment for elders (1 Timothy 5:17–18). [21]

Summary

Thus, on what parts of the Old Testament and to what extent can it be taught? The answer is all of it (2 Timothy 3:16) together with any Old or New Testament modifications that need to be included to show changes in God’s Eternal Law over the various dispensations. [22] The Old Testament is not taught as a binding system of external law like the Law of Moses, but as the greatest revelation of God’s Eternal Law. In the Church Age under the New Covenant, the law is not as a yoke about the neck (Acts 15:10), but is part of the all Scripture (2 Timothy 3:16) that the Holy Spirit will internalize to give the believer direction and the mind of Christ in practical areas of Christian living. Wisdom [23] concerning the “mind of Christ” or the popular “What Would Jesus Do” in such a situation can be imparted by believers making use of the Old Testament—all Scripture—in their edification process.

—End—

Notes

- Examples include: Curtis I. Crenshaw and Grover E. Gunn, III, Dispensationalism Today, Yesterday, and Tomorrow (Memphis: Footstool, 1985); Curtis I. Crenshaw, Lordship Salvation: The Only Kind There Is! (Memphis: Footstool, 1994); and Keith A. Mathison, Dispensationalism: Rightly Dividing the People of God (Nutley, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1995).

- Charles Clough, “A Meta-Hermeneutical Comparison of Covenant and Dispensational Theologies,” CTS Journal 7 (April-June 2001): 80.

- Unless otherwise noted, biblical quotations are from the New King James Version (Nashville: Nelson, 1982).

- R.B. Thieme, Jr., War: Moral or Immoral, rev. ed. (Houston, TX: Berachah Tapes and Publications, 1974). Col. Robert B. Thieme, Jr., pastor of Berachah Church in Houston, Texas, served as one of my pastors during the Vietnam War. His theological framework is solidly Dispensational. However, his principles of capital punishment and his principles to equip believers going to the battlefield in his Biblical Doctrine of War, primarily derives from Old Testament references. Other believers, often dismiss such Old Testament based teaching as having little validity.

- G. I. Williamson, The Westminster Confession of Faith (Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1964), 141.

- Alva J. McClain, “What is ‘The Law’?” BSac 110 (October-December 1953; electronic ed., Galaxie, 1999): 333.

- Ibid., 334-35.

- Sumner Osborne, “The Christian and the Law,” BSac 109 (July-September 1952; electronic ed., Galaxie, 1999): 241.

- McClain, op. cit., 340–41.

- Roy L. Aldrich, Holding Fast to Grace (Findlay, Ohio: Dunham, 1967), 75.

- Robert P. Lightner, “Theological Perspectives on Theonomy, Part 3, A Dispensational Response to Theonomy,” BSac 143 (July-September 1986; electronic ed., Galaxie, 1999): 235.

- Ibid., 241-45.

- An excellent volume of essays that presents the issue of continuity and discontinuity between the testaments from a variety of perspectives is John S. Feinberg, ed., Continuity and Discontinuity: Perspectives on the Relationship Between the Old and New Testaments (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 1988).

- David A. Dorsey, “The Law of Moses and the Christian: A Compromise,” JETS 34 (September 1991; electronic ed., Galaxie, 1999).

- J. Dwight Pentecost, Things to Come (Findlay, Ohio: Dunham, 1958), 121–25.

- Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., “God’s Promise Plan and His Gracious Law,” JETS 33 (September 1990; electronic ed., Galaxie, 1999): 298.

- Ibid. quotes Bruce K. Waltke, “The Phenomenon of Conditionality Within the Unconditional Covenants,” in Israel’s Apostasy and Restoration: Essays in Honor of Roland K. Harrison, ed. A. Gileadi (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988), 136-37.

- Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum, Israelology: The Missing Link in Systematic Theology (Tustin, CA: Ariel Ministries, 1989), 355.

- Robert P. Lightner, “Theological Perspectives on Theonomy, Part 3, A Dispensational Response to Theonomy,” BSac 143 (July-September 1986); electronic ed., Galaxie, 1999), shows why the Law of Moses cannot be the Christian’s way of sanctification.

- Rousas John Rushdoony, The Institutes of Biblical Law (Nutley, NJ: Craig, 1973), 10–11.

- Ibid., 11-12.

- Changes include marriages to near kin in Adam’s day before the law of Moses, the modified prohibitions outlined in Leviticus 18, changes in the sacrificial system of Moses’ Day, and their fulfillment and cessation in Christ as Hebrews teaches.

- Thomas Ice answered a question after reading a conference paper about twenty years ago concerning the current use of the Law (of Moses). He considered it as “Wisdom Literature” for giving the believer wisdom. I take this a step farther by proclaiming that as a part of the all Scripture being profitable and under the spiritual blessings of the New Covenant (for the Church), it is absolutely necessary for the believer to fully understand the mind of Christ. Unlike the Law of Moses, God no longer imposes His Law as an external system. Even so, it forms background principles which are obviously a part of God’s Eternal Law. The believer has truths internalized as laws written upon the heart for functioning spiritually under the walk in the Spirit with an even higher spiritual standard than the original letter of the Law. Thus, to ignore approximately two thirds of the Bible in favor of the last one third is to do ourselves a great disservice.

No comments:

Post a Comment