2 Sam 1:17–27 introduces and records David’s lament over the deaths of Saul and Jonathan. Examination of the textual tradition upholds the integrity of the MT as represented in BHS. Significant lexical problems are considered and suggestions made toward their solution. Consideration of the structure of the lament proper (vv 19–27 ) reveals David’s skill as a poet, while analysis of the content shows David’s grief over the deaths of two men with whom he had very different relationships—Saul as a warrior of Israel, yet David’s persecutor, and Jonathan as an intimate friend. On a broader level in the Samuel narrative, the lament is a fitting tribute to the tragic hero Saul while also contributing to the story of David’s accession to the throne of Israel.

* * *

Introduction

David’s lament over the deaths of Saul and Jonathan in 2 Sam 1:17–27 is a superb example of Hebrew poetry. William L. Holladay notes that “Critics have affirmed with one voice the literary quality of this poem.” [1] Keil and Delitzsch say, “It is one of the finest odes of the Old Testament; full of lofty sentiment, and springing from deep and sanctified emotion.” [2] Stanley Gevirtz praises it as “a genuine expression of deep sorrow and a masterpiece of early Hebrew poetry.” [3] Peter R. Ackroyd wrote, “The poem is a superb work of art, its structure skilfully developed.” [4] Hans Wilhelm Hertzberg states that this lament “has been called the most beautiful heroic lament of all time.” [5]

The beauty of this piece of literature, however, does not readily yield itself to the modern reader. Several difficulties confront the interpreter. First, one encounters several textual problems. As a result, whole articles have been devoted to “reconstructing” a readable text for 2 Sam 1:17–27. [6] There are also several lexical possibilities for certain words, forcing the interpreter to make a decision. Further, the structure of this poem is highly complex, employing a wide variety of literary devices known in Hebrew poetry. [7] These factors combine to make exegesis of this passage hazardous, but, if skillfully accomplished, rewarding.

Certain matters must be attended to, however, before attention is turned to the text itself. These include the date, authorship and historical background of the lament.

Date and Authorship

Although there is considerable discussion concerning the state of the received text, there is a general consensus of opinion that this lament is truly Davidic in origin. Hertzberg says, “There is no reason for doubting David’s authorship.” [8] Holladay remarks, “critics have never doubted its authenticity to David.” [9] The fact that, as Gevirtz notes, “The lament was a recognized literary genre in David’s day, having had a venerable tradition in the ancient Near East,” [10] lends credibility to Davidic authorship.

Smith argues that it is unlikely that someone else may have written this lament. He says,

There seems to be no reason to doubt the genuineness of the poem. One negative reason in its favour seems to be of overwhelming force: it has no religious allusion whatever. The strong current of tradition which early made David a religious hero, renders it improbable that any one should compose for David a poem which contains no allusions to Yahweh, to his relation to Israel, or to his care for Israel’s king. A similar argument is the absence of any allusion to the strained relations which had existed between Saul and David. That David should show true magnanimity in the case is not surprising. But it would hardly be human nature for an imitator not to make at least a veiled allusion to David’s experience at the court of Saul and during his forced exile. With these negative indications we must put the absence of any positive marks of a late date. There seems to be absolutely nothing in the poem which is inconsistent with its alleged authorship. [11]Of course, there are several positive indications of Davidic authorship as well. First, it must be remembered that David was not only a skilled musician, but also a genius in giving poetic expression to his thoughts. [12] It is for this reason that he is known as the “sweet singer of Israel.” The text in 2 Sam 1:17 clearly attributes the lament to David: ויקנן דוד את־הקינה הזאת13 /”Then David lamented this lament.” David’s respect for Saul as “the LORD’s anointed” is clearly seen in these verses (esp. vv 22–24), and this is consistent with the tradition found in 1 and 2 Samuel (see 1 Sam 24:5–6, 10; 26:9–11, 16, 23; 2 Sam 1:14–16). Never, however, does the lament hint of a friendship between David and Saul. However, in its treatment of Jonathan, the lament speaks of a deep emotional attachment (esp. v 25). This is also consistent with the tradition of 1 and 2 Samuel (see 1 Sam 18:14; 20:2–17 [note also the charged emotional atmosphere of this whole chapter]; cf. David’s treatment of Jonathan’s son after Jonathan had been killed: 2 Sam 9:1–13; 21:7). Thus, the lament accurately and precisely reflects the relationships David sustained with both Saul and Jonathan.

When it is thus seen that the lament is Davidic, the date easily follows. The text gives a specific indication of the amount of time that lapsed between the death of Saul and the reporting of his death to David-three days (2 Sam 1:1–2). The text does not indicate any amount of time transpiring between David putting to death the Amalekite messenger and his composing this lament. There is no reason to suggest that David would have needed more than a few hours to compose it (given his poetic genius), so it is likely that it was written within hours after David heard of the deaths of Saul and Jonathan. This would establish the time of composition as about 1010 B.C.

Historical Background

David’s lament comes in a strategic position in the Samuel narrative. It is in the transitional period between the reign of Saul as king over Israel and the establishment of the Davidic dynasty. However, the relationships between David and Saul and Jonathan go back far earlier.

There is a conflict between David and Saul concerning the right to rule over Israel. Saul is first anointed by Samuel as king over Israel (1 Samuel 10). However, as a result of Saul’s continued disobedience, Yahweh rejected him as king over Israel (1 Samuel 15) and Samuel anointed David as the next king (1 Samuel 16). However, this did not mean that Saul was immediately removed from office. David had to await Saul’s death before his accession to the throne.

Open conflict between David and Saul began after David defeated Goliath (1 Samuel 17). As victorious Israel was returning home, the women of Israel came out to meet them, singing, “Saul has slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands” (1 Sam 18:7). As a result, Saul became very jealous of David and sought to kill him the next day. In contrast to David’s relationship with Saul was the development of a friendship between David and Jonathan. 1 Sam 18:3 says, “Jonathan made a covenant with David because he loved him as himself” As the narrative continues, Saul’s actions became increasingly psychotic. Occasionally, he tried to kill David in fits of rage but at other times he meekly sought reconciliation with him. However, the situation became progressively worse until David was forced to flee from Saul. However, before he fled, his friendship with Jonathan was confirmed: a pact was made between them that when David’s enemies had been overthrown, David would not kill Jonathan’s descendents (who would be rivals to the throne) (1 Sam 20:14–17). Jonathan thus recognized that David was destined to rule over Israel, something Saul knew as well, but tried to prevent (see, e.g., 1 Sam 20:31).

David fled into the Hill Country of Judah. There he began to gather a band of fugitives, malcontents, and n’er do wells (1 Sam 22:1–2). With this band, David began to raid the Philistines. Saul, however, kept hunting for David. Because of this, David eventually decided to try to find protection in a Philistine city, Gath, but while there, he secretly continued his raids on other Philistine towns. In time Achish, king of Gath, asked David to join the Philistines in a battle against Israel, and it appears that David was ready to do as he was asked, but the other Philistine commanders objected to his presence among them, so he was sent away (1 Samuel 29). [14] This Philistine coalition then joined battle with Israel on Mount Gilboa. [15] There Saul and Jonathan were killed (1 Samuel 31).

News of their death reached David via an Amalekite messenger. The Amalekite claimed that he dealt the death blow to Saul, hoping to be rewarded for this act (cf 2 Sam 4:10). David reacted by killing the man because he had lifted his hand to destroy the LORD’s anointed (2 Sam 1:14). Soon afterward, David expressed his grief over the deaths of Saul and Jonathan in the lament found in 2 Sam 1:17–27.

Following the lament, the writer of 2 Samuel narrates the account of David’s confirmation as king over Israel. David was immediately anointed king over Judah at Hebron (2 Sam 2:4). However, Ish-Bosheth, a son of Saul, succeeded his father’s throne, and war broke out between the two houses. The tide of the battle was turned in favor of David when Abner, commander of Israel’s army, had a falling out with Ish-Bosheth, and went over to the side of David. A bloodbath followed resulting in the murder of both Abner and Ish-Bosheth. During the next seven and one half years, David consolidated his position, resulting in his being anointed king over all Israel at Hebron (2 Sam 5:1–3).

Gevirtz has made some helpful suggestions about the relationship of all this historical background to the lament in 2 Sam 1:17–27:

Moreover, it may perhaps be hazarded, for the deaths that he here bewails David may have felt at least in part responsible. It was in the service of Saul that David had risen to prominence as a military leader, gained the love of Saul’s daughter, Michal, and her hand in marriage, becoming son-in-law to the king, and won the selfless friendship of Jonathan, the heir apparent, who risked the violence of his father’s anger—and therein his very life—defending David. Then, hunted as an outlaw leader of an outlaw band, David sought and gained service with Achish, the Philistine king of Gath. Sometime after, in concert with the other four Philistine rulers, Achish joined battle with the Israelite forces in the fateful encounter at Gilboa in which Saul and Jonathan lost their lives. Though he was excused from participating in this engagement, one may wonder, on the basis of his avowed willingness to fight on the Philistine side against Israel and his failure to come to the sorely needed help of those to whom he owed so much, whether David is not “overcompensating” in his lament for a guilty conscience. [16]This is an interesting possibility, but it is extremely difficult for the modern reader to fathom the psychological motivations that prompted an ancient author. Nevertheless, it is evident that the lament is the result of David’s deeply emotional reaction to the news that Saul and Jonathan had been slain on the battlefield.

With this background, it is now time to turn to the lament proper. Here, problems must be faced and, as far as possible, resolved, if the lament is to retain its full force. The first problem that requires discussion is the textual problem.

The Text of 2 Samuel 1:17-27

The MT text of 2 Sam 1:17–27 [17] has many difficult readings. William L. Holladay notes, “because of its textual difficulties (for which the ancient Versions are of little help), critical studies of the poem which appeared in the period 1870–1930 tended to concentrate upon the attempt to restore a satisfactory text.” [18] Among commentators one finds such statements as, “We can do nothing with the text as it stands.” [19] This has led to suggestions for extensive emendations of the text. [20]

It is necessary to lay down some guidelines to control the amount of emendation to the MT that will be allowed. I suggest the following guidelines. 1) Acceptance of an emendation must be viewed as the exception, not the rule, in handling the text. 2) An emendation must not be proposed solely on the basis of the difficulty of the MT reading. Rather than emend a difficult reading, it is better to leave it uninterpreted in the hope that further research in Semitic languages might bring to light new knowledge that would render the difficulty intelligible or that new manuscript evidence would be found which would suggest a different reading. Conjecture must never be supposed to take the place of evidence. Therefore, 3) emendations to the MT may be proposed if there is sufficient ancient manuscript evidence for a change. 4) Emendations may be considered if it can be shown how a scribe would have made an error that resulted in the MT reading. And 5) “emendations” will be considered if it can be demonstrated that a certain scribal practice resulted in an abnormal reading. This last point is relevant to the discussion on v 26 below. What is suggested there is not really an emendation, but an alternate way to understand the MT text. With these guidelines in hand, proposed emendations of 2 Sam 1:17–27 will be considered.

Verse 18

וַיֹּאמֶר לְלַד בִּנֵי־יְהוּדָה קָשֶׁת הִנֵּה כְתוּבָה עַל־פֶר הַיָּשָׁר׃

A variety of emendations have been suggested for v 18. The only significant variation among the versions used in this study [21] was that the LXX omitted the Hebrew term קשת. However, this does not affect the proposed emendations, none of which are based on manuscript evidence.

Part of the difficulty one must face is whether v 18 is to be included in the lament proper. Most of the emendations proposed are suggested on the assumption that v 18 is part of the lament. However, structural analysis of the lament reveals that v 18 falls outside the boundaries of the lament.

Gevirtz offers the most extensive emendation of the text, incorporating most of the suggestions made by others. [22] The following shows the BHS text next to the emended version offered by Gevirtz:

The meaning of Gevirtz’s emended text is, “(With) a bitter wailing, weep O Judah! (With) a grievous lament, mourn O Israel!” compared to the BHS reading which he translates, “To teach the sons of Judah (a/the) bow; Behold, it is inscribed in the book of the upright.” [23] As can be seen, this is a very extensive revision. While some of these changes may be seen as plausible, at least four of them seem unlikely based on the evidence. First, it is difficult to see how the י which Gevirtz adds at the beginning would have dropped out completely. Second, there is evidence that the ancient scribes practiced word division. [24] Therefore, it is unlikely that the ל and מ in ללמד should be separated. Third, Gevirtz offers no explanation of how הנה became נהי, and it is difficult to see how this would have happened. Finally, Gevirtz must resort to the desperate explanation that כתובה על “must be regarded as an explanatory addition inserted, once the corruption of the text had gotten under way, in a last desperate attempt to give some order to what by that time had developed into hopeless chaos.” [25] One final word that may be added is that it is difficult to see how so many errors crept into the text in so short a space. When all these factors are added together, it seems unlikely that Gevirtz has reconstructed the “original” text.

Verse 21

הָרֵי בַגִּלְבֹּע אַל־טַל וְאַל־מָטָר עֲיכֶם וּשְׂדֵי תְרוּמֹת

כִּי שָׁם נִגְעַל מָגֵן גִּבּוִֹרִים מָגֵן שָׁאוּל בְּלִי מָשִׁיחַ בַּשָּׁמֶן׃

The phrase ישדי תרומת has been widely discussed since Ginsberg proposed in 1938 that it be emended to ושדע תהומת.26 Ginsberg found a basis for this emendation in the tablet of the Ugaritic epic Dnʾil. Since the time he made this proposal, it has been widely accepted. [27] Smith, however, would emend the text to read שדות המות, “fields of death,” [28] and in this he is followed by Mauchline. [29] However, it is not necessary to emend the text for it to make sense here. Instead, the problem may be solved lexically (see below, p. 108). Thus, following the guidelines laid down above, the suggested emendations of this verse are rejected.

Verse 24

בְּנוֹת יִשְׂרָל אֶל־שָׁאוּל בְּכֶינָה הַמַּלְבִּשְׁכֶם שָׁנִי עִם־עֲדָנִים

הַמַּעֲלֶה עֲדִי זָהָב עַל לְבותְכֶן׃

A slight problem is found in v 24. This involves the interchange of a masculine and feminine suffix, when the feminine suffix is expected in both cases (המלבשכם/לבושכן). It is probable that this error crept into the text early. In the early orthography of Hebrew, the מ and נ were very similar in appearance. [30]

Verse 26

צַר־לִי עָלֶיךָ אָחִי יְהוֹנָתָן נָעַמְתָּ לִּי מְאֹד

נִפְלְאַתָה אַהֲבָתְךָ לִי אַהֲבַת נָשִׁים׃

In another verse difficult to understand, the word נִפְלְאַתָה has come under scrutiny as a candidate for emendation. As the verb stands, it is an anomalous niphal perfect, 3rd feminine singular (the ordinary form being נִפְלָאת).31 Holladay remarks that נִפְאת (feminine plural participle) is the expected form, but retains the MT pronunciation as an archaic form. [32] Cross and Freedman, however, have suggested an emendation that better fits the evidence and sense of the verse. They suggest that “This anomalous formation is probably the result of the loss of an aleph by haplography.” [33] This suggestion is based on a known scribal practice of a consonant (or in some cases consonants) being written once when strict grammatical construction demands that it be written twice. [34] Thus, written fully the phrase would read, נִפְלָא אַתָּה/”You are wonderful.” If this emendation is accepted, a nice couplet is formed with the next phrase, אַהֲבָתְךָ לִי/”your love was mine.”

While the text of 2 Sam 1:17–27 has some hard readings, on the whole the manuscript evidence supports the MT reading. Because of this, and on the basis of the above discussion, I reject most of the proposed emendations. [35] My reasons for doing this will become clearer in the following discussions. However, the emendation (which technically might not be considered an emendation) in v 26 is accepted, as is the emendation in v 24 .

Lexical Considerations

Once a working text has been established for 2 Sam 1:17–27, there still remains some difficult lexical problems to be solved. Sometimes none of the meanings of a word seems to fit the context, while at other times more than one meaning makes good sense. Perhaps this is partly due to the poetic nature of the passage. Poetry in any language often stretches the ability of a language to communicate ideas to its limit. Furthermore, poetry (and Hebrew poetry is no exception) often uses archaic words, which adds to the lexical difficulty. Several key words need to be considered in David’s lament.

הצבי

The confusion regarding this word is reflected in the versions. As vocalized in the MT, it is a noun which means either “beauty, honor” (based on צבה II) or “gazelle” (based on צבה III). [36] However, the Aramaic Targum Jonathan has אתעתדתון, an ithpael of עתד, which in this stem means “to be ready.” [37] Holladay reasons from these facts as follows:

This ithpael of ʿtd serves as a passive (or intransitive) of the pael; the pael of this verb regularly translates nṣb hiphil. That is, the Targum strongly suggests our reading a Hebrew niphal in the present instance. The verb nṣb fits nicely into our context. [38]This would require repainting the MT הַצְּבִי as הִצָּבִי a feminine imperative meaning “take one’s stand.” [39] The vocative, Israel, would then be seen as a personified woman.

The LXX, however, offers a different possibility. It translates הצבי by Στήλωσον, an aorist imperative meaning, “set up as a στήλη or monument.” [40]) This is a translation of the hiphil of נצב, which would be pointed הַצִּבִי meaning, “set up, erect (a pillar).” [41]

The Vulgate, however, reflects the Hebrew pointing of the MT text. The Vulgate has the word incliti from inclutus, meaning “glorious, famous, illustrious, renowned, celebrated” [42] (indicating צבה II was understood).

The differences among the versions at least verify the consonantal text of the MT. The next question that may be asked is whether a verb form (with the Aramaic Targum Jonathan and the LXX) or a noun form (with the MT and the Vulgate) is to be expected. The parallelism exhibited between v 19a and v 25b [43] suggests that a noun form is expected. However, structural analysis of the lament reveals that there is no structural connection between these two lines (see below, pp. 111-15). Nevertheless, the semantic parallelism strikes the reader with such clarity that on the reading of v 25b he is naturally reminded of v 19a. O’Connor has called this a “fake coda,” that is, a fake ending to the lament. [44] The true ending (v 27) does have a structural relationship with v 19 where כלי מלחמה stands in a chiastically arranged parallelism with הצבי ישראל. Both the fake ending and the true ending use nouns which correspond in the respective parallelisms to הצבי. Therefore, it can safely be asserted that הצבי should be taken as a noun form and not a verb form.

However, this still does not solve the lexical problem of deciding whether הצבי means “beauty, honor” or “gazelle.” Commentators are divided over which of these meanings to accept. In the Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, 2 Sam 1:19 is cited as an example of the meaning of “glory” for צבה II, and it is said that the expression refers to King Saul. [45] Mauchline says, “The term should…be rendered as ‘glory’ with reference to Saul and Jonathan or to the ‘glory,’ the national prestige and dignity of Israel as a whole.” [46] Others, however, take the meaning “gazelle.” Freedman says, “the use of animal terms to represent human figures is common both in biblical and Ugaritic literature.” [47] Because of the parallelism between vv 19 and 25, Freedman applies the term to Jonathan. [48]

If the term means “gazelle,” it provides interesting imagery for the verse. 2 Sam 2:18 and 1 Chron 12:9 indicate that the term can be used in reference to warriors. The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible says, “Gazelles had to be hunted…but they were not easy to bag, for their speed of movement was proverbial.” [49] Thus, the term would be a fitting term for a military leader.

However, it is not necessary to determine either one meaning or the other for the term הצבי. Indeed, Freedman remarks, “The terms may well have a common etymology, since the gazelle is characterized by its beauty and grace, as well as its speed.” [50]

Paralleling the ambiguity of meaning is the ambiguity of reference. The semantic parallelism between vv 19a and 25b suggests that the term should be applied to Jonathan, but the structural parallelism between vv 19a and 27b suggests that the reference is to both Saul and Jonathan. The meaning “gazelle” would be a fitting epithet for Jonathan, who was a noted military leader (see 1 Sam 14:1–13; 24–45). The meaning “beauty, honor” can be understood as a collective, figurative reference to both Saul and Jonathan (i.e., Saul and Jonathan, as the leaders of the nation, are the beauty of Israel). Thus, it seems that David used the ambiguous term and the somewhat ambiguous structure not to confuse, but to give fuller meaning to his words. Saul is not slighted, but Jonathan is given a certain preference. [51]

במותיך

Traditionally this term has been understood to mean, “in your high places.” [52] When it has this meaning, Gevirtz insists that it has a technical sense of a place of worship, [53] which is out of place in this context. He also objects to the traditional translation because “Gilboa, the scene of the heroes’ deaths, was [not]…Israel’s.” [54] Therefore, Gevirtz suggests the translation “thy slain bodies.” He finds support for this translation in Ugaritic studies which have shown that the term במת in biblical Hebrew may mean “back” and came to denote “body,” and the fact that a pronominal suffix may intervene in a construct chain and refer to the whole chain. [55] However, such convoluted reasoning is not necessary. במה does not need to have the technical sense Gevirtz suggests. [56] Furthermore, Israel may have claimed Gilboa as their territory even though they did not have undisputed control of the area. Therefore, it is best to retain the traditional understanding of the term.

תרומתּ 57

BDB and Holladay list similar meanings for this term. According to BDB it means, “contribution, offering, for sacred uses.” [58] Holladay says it means, “tribute, contribution (at the cult).” [59] Keil and Delitzsch, accordingly, understand the meaning of the phrase in which this word is found to be, “‘and let not fields of first-fruit offerings be upon you,’ i.e. fields producing fruit, from which offerings of first-fruits were presented.” [60] Freedman, however, offers an alternative understanding of the term. He would translate ושדי תרומת as “Even you lofty fields.” [61] Fokkelman offers a good defense of this understanding. He says,

תרומת is a poetic plural which means “high position.” It is true that in all other cases in the OT the word means “offering, cultic contribution,” but I would like to point out that the words of the root rûm do not usually have such a specific and so extremely limited semantic field at all. rûm, “be high, elevated” can be used for such divergent matters as limbs, objects and persons; it also occurs in a figurative sense. It is quite conceivable that, in keeping, the word terûmā must originally have had a wider field of meaning and that only in the course of the history of scriptural language it was limited to a specific cultic use. I suppose that II Sam 1 21 is the only evidence extant in the limited selection of the classical Hebrew literature which is called the OT terûmā has the same meaning there as the masc. marôm. The semantic identification of a noun with mem praeformans and a noun with taw praeformans is admissible. [62]When this suggestion is accepted, the difficulty of the term is relieved without emendation of the text. Therefore, this understanding will be accepted.

מגן

One final term that bears mention is the term מגן in v 21b. The meaning is normally understood as “shield,” but Freedman interprets the term as “benefactor, suzerain, chieftain,” and offers Ps 84:10 as an example of this meaning. [63] However, there is no need to turn to a secondary usage of this word. As Shea argues, “Considering the Palestinian provenience and the early date of 2 Samuel 1, ‘shield’ seems the more likely translation of mgn here.” [64]

With this lexical discussion in mind, it is now time to turn to the passage as a whole. The next section will analyze the structure of the lament.

Structural Analysis

The skill of David as the “sweet singer of Israel” is clearly displayed in this lament. David employed many of the poetic devices the Hebrew poet had available to produce an elegant, yet tightly structured lament. Furthermore, he did this in spite of the difficulty he faced in eulogizing in a single poetical unit two men with whom he had very different relationships. Holladay well summarizes David’s problem:

David faced a unique problem here: his lament is for two fallen heroes, with each of whom he had a very different relationship. Now it is never easy to compose a eulogy for two at the same time, and it is still harder to compose a eulogy for two when the relationships are so very different as David’s with Saul and Jonathan…. That he succeeded in a way which gives complete esthetic satisfaction is the measure of his skill. [65]The first question that needs to be asked when studying the structure of this lament is, “where does the lament begin?” Both Smith [66] and Driver [67] follow Klostermann in seeing ויאמר in v 18 as the introduction to the lament. This suggestion forces them to offer emendations of the MT for v 18 because as it stands, it cannot be part of the lament. However, they have no textual support for the emendations they suggest. Rather than assuming ויאמר must immediately precede the lament, it is a better procedure to see if the text makes sense as it is before suggesting that the text be emended. This verse does make sense as an introductory instruction for the lament; therefore, the following structural analysis will begin with v 19.

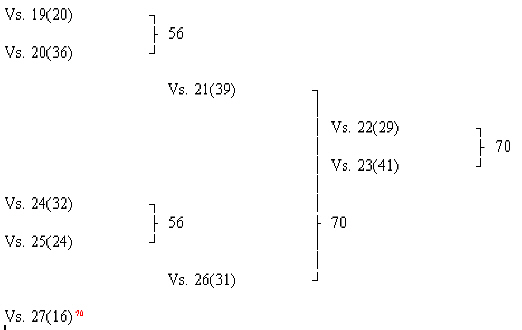

Several recent works have dealt with the structure of 2 Sam 1:19–27. [68] Shea suggests the following structure for the lament:

[69]

The “Qinah couplet” consists of a tricolon plus a bicolon. Shea’s theory of the structure, however, breaks up the syntax of the lament. For example, he reads v 23 in the following way:

Saul and Jonathan,

who were beloved and graceful

in their life and in their death

they were not separated.

They were swifter than eagles,

They were stronger than lions.

I agree that the last two lines form a bicolon. However, his first three lines form a tightly structured bicolon as well. The Hebrew reads:

שאול ויהונתן הנאהבים והנעימם

בחייהם ובמותם לא נפרדו

Here, a plural subject to the sentence is followed by two modifiers (participles in apposition to the subject). The last part begins with two modifiers (adverbial prepositional phrases) followed by a plural verb. Thus, there is a syntactical unity with the subject and verb at the extremities of the bicolon surrounding two sets of two modifiers. Thus, Shea’s “Qinah couplet” (a central factor in his analysis) is found not to exist (at least in this case), invalidating his structuring of the lament. Therefore, an alternate structure must be sought.

Freedman has done extensive work with the metrical structure of the lament. On the basis of syllable counts he proposes the following structure:

[70]

Freedman says, “The individual units vary in length but when combined in accordance with their distinctive characteristics (key words or phrases), the larger groups are evenly matched.” [71] This makes a nice numerical scheme, but unfortunately it does not fit these verses semantically (e.g., the subject matter of v 21 is not closely related to that of v 26). Furthermore, this structuring leaves v 27 isolated from the rest of the lament in spite of its parallelism with v 19. Therefore, this scheme too is inadequate.

O’Connor has also done extensive work on the structure of 2 Sam 1:19–27 in Hebrew Verse Structure. He analyzes the lament as a long stave [72] of 30 lines. The first two and the last two lines (vv 19 and 27) he sees as the burdens of the lament with a fixed inner line (v 19b and v 27a) and a free outer line (v 19a and v 27b). Enveloped by the burdens are 4 batches, the first two consisting of 8 lines of 4 couplets each (vv 20–21 and vv 22–23) and the last two consisting of 5 lines each. The third batch (vv 24–25) begins with and the fourth batch (v 26) ends with a 3 line group; the third batch ends with and the fourth batch begins with a 2 line group. Thus, the last two batches form a 3:2/2:3 pattern. [73]

O’Connor’s lineation of the lament arises from his analysis of the interaction of two strictures at play in the structuring of Hebrew verse. [74] The first stricture is syntactic; the second stricture he calls “troping,” which refers to a broad range of phenomena including (among other things) various forms of parallelism, repetition, matching, gapping, coloration, and mixing. [75] The structure, then, arises in the interaction of syntax with tropes. This method of analyzing structure overcomes the limitations evident in both Shea’s and Freedman’s analyses. A detailed diagram based on O’Connor’s lineation and grouping of lines along with a basic analysis of the interrelation of parts is found in the Appendix to this article. The following structural analysis of 2 Sam 1:19–27 relies heavily upon O’Connor’s analysis of the lament.

An inclusio is formed by vv 19 and 27, uniting the whole lament. Both verses are composed of a single bicolon. The second colon of v 19 and the first colon of v 27 read exactly the same: איך נפלו גבורים. Thus, the inclusio is chiastically arranged. There is a further chiastic arrangement (both syntactic and semantic) between v 19a and v 27b. The last word of v 19a is the verb, חלל, while the first word of v 27b is also a verb, ויאבדו; both have reference to death. הצבי ישראל and כלי מלחמה are thus found to be matching terms with על־במותיך of v 19a dropped out in v 27b.

The first batch of the lament is found in vv 20–21. This unit consists of four bicolons. The syntax of these lines divides the bicolons into two sets of two bicolons. The first set is found in v 20. Here a bicolon of two main clauses is followed by a bicolon of two subordinate clauses. O’Connor calls this clause mixing. [76] Both bicolons are set in direct parallelism, but with בחוצת of v 20b gapped out of v 20a. The first bicolon examples geographical binomation; [77] that is, the bipartite geographical titles refer to the whole geopolitical region encompassed by the points of reference. Thus Gath, standing at the eastern edge of Philistine territory near the hill country of Israel, and Ashkelon by the sea represent all of Philistine territory. Exhibited in the second bicolon of v 20 is an adjectival combination. [78] The first line of the bicolon uses a noun (פלשתים) and its match in the second line is an adjective (הערלים). Thus, it is the daughters of the “uncircumcised Philistines” who are not to rejoice at the deaths of Saul and Jonathan.

The second set of bicolons in the first batch is found in v 21. The subordinating conjunction כי in v 21c binds the bicolons together. There is a chiastically arranged match in the first bicolon. Syntactically, the match can be analyzed as vocative/predicate/subject//subject/predicate/vocative. [79] Recognizing this structure aids the interpreter in understanding ושדי תרומת at the end of v 21b. This phrase matches הרי in v 21a, indicating that a technical sense is not in mind here (cf. discussion above, p. 108). The ו on ושדי is emphatic. [80] Repetition is employed in v 21c-d with מגן. These two lines are a poetic expansion of the idea, “because there lies the shield of mighty Saul no longer anointed with oil.”

The second batch is found in vv 22–23. Like the first batch, this batch has two sets of two bicolons. The first set is found in v 22. Each bicolon uses direct syntactic parallelism. The two bicolons of this verse are combined by the use of phrase mixing; [81] two phrases are followed by two main clauses. There is a formal relationship of the first phrase with the first clause and the second phrase with the second clause (an alternating structure of ab:a’b’), but the effect of the mixing is to unite all the elements (i.e., “from the blood/fat of the wounded warriors, the bow/sword of Jonathan/Saul did not return empty”).

The second set of this batch is related to the first batch through the repetition of the royal names Saul and Jonathan. The use of the plural subject “Saul and Jonathan” in v 23a confirms the analysis that the elements in v 22 are all united. As was noted earlier (p. 110), there is a syntactic unity in the first bicolon of v 23 with a plural subject and a plural verb surrounding two sets of two modifiers. The last bicolon exhibits direct syntactic parallelism.

There is a further structural pattern in this second batch. The first bicolon (v 22a-b) and the last bicolon (v 23c-d) of the batch each consists of two lines of two elements per line set in direct syntactic parallelism, thus enveloping the batch. The middle four lines are each composed of three constituents. [82]

Verses 24–25 comprise the third batch. The five lines of this batch form a tricolon followed by a bicolon. In the tricolon, the first line is a main clause and is followed by two dependent clauses. Each line has three constituents and there is syntactic matching between the two dependent lines. Further, the two dependent lines are bound together by the assonance of the first word, המלבשכן,83 and the last word, לבושכן. As noted earlier, v 25 is a fake coda.

The last batch (v 26) is similar to the third batch in that it has five lines, but this time the bicolon is followed by the tricolon. Employed in v 26a-b is what O’Connor calls personal binomation, in which the name and title of a person are inextricably bound together. [84] The arrangement of this feature here is chiastic, with the title [85] found at the end of the first line and the name found at the beginning of the second line. The tricolon (v 26c-e) is formed with three verbless clauses, each having two constituents. [86] There is alternation in the syntactic pattern, with v 26c, e arranged predicate—>subject and v 26d arranged subject—>predicate. This structure results in a variation of the placement of the repeated term אהב in v 26d, e.

Structural relationships may also be found traversing the batch boundaries. The first batch relates to Saul; the fourth batch to Jonathan. Saul’s name is found in the second half of the first batch; Jonathan’s name in the first part of the fourth batch. The second and third batches speak of both Saul and Jonathan. The first set of bicolons in the second batch treats Jonathan, then Saul; the third batch treats Saul, then Jonathan—a chiastic arrangement which envelopes the treatment of Saul and Jonathan in the second set of bicolons in the second batch. A contrast may be seen between the daughters of the uncircumcised Philistines (v 20) and the daughters of Israel (v 21). There is a structural similarity between the first and second batches. Both are formed by two sets of two bicolons. The opening set of bicolons are structured similarly with the first batch using clause mixing and the second batch using phrase mixing. The use of the plural גבורים in v 21c in a bicolon referring to Saul is echoed in v 25a in a bicolon referring to Jonathan. The word אהב is repeated in v 23a and v 26d, e. The bicolons found in the third and fourth batches both speak of Jonathan. The trope of repetition is found at the end of the first batch and the end of the fourth batch. These trans-batch relationships unify the whole lament.

The personal references to Saul and Jonathan are a major unifying factor in the lament. However, the references are also a point of tension, given David’s personal relationships to these men. O’Connor makes the following perceptive remarks on the structure of the lament and this tension:

There is no structural reading of the Lament based on linguistic criteria which will resolve the tension of reference in the poem, because it is a genuine tension; similarly, some doubt will always attach to the explication of the epithet ‘the Gazelle’. The poem is about Saul and Jonathan; and, further, it is more about Jonathan. The treatment of Saul is split over two loci, 21cd and 24abc. The split has the effect of setting Saul up as dominant over the whole poem. In contrast, six of the seven or six lines treating Jonathan occur together. These six (despite their blocking) balance Saul’s five because they include the last batch of the poem. Further, Jonathan is treated in the fake coda, 25b. The reading of the first line is not crucial in working out Jonathan’s place in the poem’s scheme, because even if it refers to Saul, Jonathan’s lines still have greater structural prominence. The poem is diverse in its use of resources: it does not slight Saul, while giving prominence to Jonathan. [87]From this structural analysis of David’s Lament, his skill as a poet becomes obvious. Translation of 2 Sam 1:17–27 and a few exegetical remarks will close this discussion of 2 Sam 1:17–27 proper before an attempt is made to understand this portion in its literary context.

Translation and Exegetical Remarks

The problems encountered thus far have been solved sufficiently to allow a tentative translation of the text and for exegetical remarks to be made. This will be done in this section in a verse by verse format.

Verse 17

וַיְקֹנֵן דָּוִד אֶת־הַקִּינָה הַזֹּאת עַל־שָׁאוּל וְעַל־יְהוֹנָתָן בְּנוֹ׃

Then David uttered this lament over Saul and over Jonathan his son.

This verse is the basic introduction to the lament of vv 19–27. The term קינה/”lament” is used of a formal utterance which expresses grief or distress. [88] It is to be distinguished from the word group having the root ספד which “covers most of the spontaneous vocal expressions of grief, whether uttered by hired mourners or by those who were affected by the bereavement.” [89] The קינה on the other hand, could be learned and practiced (cf. Jer 9:9). Cross and Freedman remark that 2 Sam 1:19–27 “is a typical lamentation or Qinah [although] it is not composed in the elegiac rhythm of later times, but has precisely the same metrical and strophic form as the victory hymns.” [90] While the analysis presented here rejects Freedman’s metrical scheme as a structuring device for the lament, perhaps there is a point to be made that the metrics of the text are a subtle indication of what follows in the text: David becomes king over Israel in place of the house of Saul.

Verse 18

וַיֹּאמֶר לְלַד בְּנֵי־יְהוּדָה קָשֶׁת הִנֵּה כְתוּבָה עַל־פֶר הַיָּשָׁר׃

And he commanded that it be taught to the men of Judah. The Bow. Written in the book of Jasher.

Some of the problems connected with this verse have been noted earlier (see above, pp. 101-2,109–10). The term קשת is awkward and seems to stand independent of the rest of the verse. Since, as was said above, there seems to be no evidence for a legitimate emendation of the verse, it seems best to take this term as the title of the lament. Keil and Delitzsch say that the title is given “not only because the bow is referred to (ver. 22), but because it is a martial ode, and the bow was one of the principal weapons used by the warriors of that age.” [91] Hertzberg suggests, “‘Bow’ may have been added to the title as a characteristic word featuring in the poem, just as, for example, the second Sura of the Koran has been called ‘the cow’.” [92] The prominence of the bow is also seen in the literary setting of the lament. Saul was critically wounded by archers (1 Sam 31:3). While the exact means whereby Jonathan was killed is not recorded, the text indicates that Saul and his sons were together in the heat of the battle (1 Sam 31:2), so it is reasonable to assume that Jonathan was killed by archers. Furthermore, Jonathan may have had skill as an archer (cf. his use of the bow and arrow in 1 Samuel 20) whereas no mention is made in the text of Saul as an archer. The title, then, may be a subtle indication of David’s preference of Jonathan.

The book of Jasher is also mentioned in Josh 10:13 and 1 Kgs 8:53 (LXX). [93] Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible says this was “A written document mentioned as though well known and containing Joshua’s poetic address to the sun and the moon (Josh 10:12–13), David’s lament over Saul and Jonathan (II Sam. 1:17–27), and probably…Solomon’s original words of dedication of the temple (I Kings 8:12–13).” [94] The term “Jasher” is a transliteration of ישר which means “straight” or “upright,” [95] indicating that the title of this collection is descriptive.

Verse 19

הַצְּבִי יִשְׂרָל עַל־בָּמוֹתֶיךָ חָלָל יךְ נָפְלוּ גִבּוֹרִים׃

The gazelle/glory, Israel, upon your heights is slain. How are the mighty fallen!

As was mentioned above, the first term of this verse, הצבי is probably purposely ambiguous both in reference and in meaning. The heights refer, of course, to Mount Gilboa, the scene of Saul’s and Jonathan’s deaths (1 Samuel 31; 1 Chronicles 10). With O’Connor, [96] I read חלל as a Qal passive. איך with the perfect is a term which expresses “Astonishment or indignation at something which has happened.” [97]

Verse 20

אַל־תַּגִּידוּ בְגַת אַל־תְּבַשְּׂרוּ בְּחוּצֹת אַשְׁקְלוֹן

פֶּן־תִּשְׂמַחְנָה בְּנוֹת פְּלִשְׁתִּים פֶּן־תַּעֲוֹּזְנָה בְּנוֹת הָעֲרֵלִים׃

Do not report it in Gath! Do not proclaim it in the streets of Ashkelon! Lest the women of the Philistines rejoice, lest the women of the uncircumcised exult!

Undoubtedly David thought that the news of the deaths of Saul and Jonathan would weaken Israel’s position in Palestine against their enemy the Philistines. Under Saul’s rule, Israel had moved away from the domination of the Philistines. As Hauer notes, “Prior to the battle [at Michmash, which was Saul’s first decisive action against the Philistines] the Philistines seemed able to work their will at the heart of the Israelite hill country. Not so afterward.” [98] However, despite this desire expressed by David, the news surely spread. Nevertheless, the news did not result in renewed military action against Israel by the Philistines. Hauer remarks,

Philistine overconfidence may have brooked larger than Israelite power in the failure to follow up the triumph at Gilboa. They may have thought the death of Saul had ended their problems with the hill people. There is no record of serious Philistine action against Israel until David was perceived as a threat…. It is not too much to say that by the very fact of his death Saul bought David the time he needed to build a military establishment capable of coping with the Philistines once and for all. [99]

Verse 21

הָרֵי בַגִּלְבֹּעַ אַל־טַל וְאַל־מָטָר עֲיכֶם וּשְׂדֵי תְרוּמֹת

כִּי שָׁם נִגְעַל מָגֵן גִּבּוֹרִים מָגֵן שָׁאוּל בְּלִי מָשִׁיחַ בַּשָּׁמֶן׃

Mountains! Let there be in Gilboa no dew. Let there be no rain on you, even you, lofty fields. Because there lies cast aside the shield of the mighty, the shield of Saul no longer anointed with oil.

The construction הרי בגלבע is unusual with a noun in the construct state followed by a noun attached to the preposition ב. Kautzsch and Cowley note this construction in “rapid narrative” as a connecting form. [100] The noun הרי is functionally a vocative, but by using a construct form, David emphasizes that the curse he utters in this verse is intended specifically for Gilboa, the land on which Saul and Jonathan were slain. [101] Fenton perceptively remarks,

The words of II Sam I 21 constitute a literary conceit. The poet (speaking in the person of David?) implies that the violent death of Saul (and Jonathan?), the fact that he was not laid to rest peacefully and buried with his weapons as appropriate (they had been taken as booty, I Sam XXXI 9–10) was so outrageous an event, so cruel a disaster, as to be as shocking as murder. In a bold hyperbole he curses the Hills of Gilboa praying that they suffer drought—the consequence of bloodguiltiness—and he does so using the ancient phrases which may still in his day have been associated with the tale of an actual murder and the actual drought consequent upon it. His equation of death in battle with murder is an extravagance intended to express the affection of David, of Israel, for Saul and Jonathan and the emotion stirred by their slaying. [102]Shea describes the mountain range which received this curse in the following terms:

Gilboa is not a solitary mountain peak, nor a series of peaks, but a ridge some eight miles long and three to five miles wide running southeast and south from Jezreel. It forms the watershed between the plain of Esdraelon and the plain around Beth-Shean, dropping away sharply to the north and east. It slopes gradually to the west, however, and on this gentle fertile terrain, barley, wheat, figs and olives are grown. The description “fields of the heights” suits this western slope to which rain and dew were denied by the curse in this poem. [103]The reason this curse is placed on Gilboa is because “the shield of Saul” lies unanointed on it. The term נגעל has the connotation “cast aside (with loathing)” [104] and this imagery is reinforced by the statement that Saul’s shield was no longer anointed. Oil rubbed on a shield was necessary to keep it in proper condition. [105] “Shield” is used here figuratively as a metonymy for Saul himself.

Verse 22

מִדַּם חֲלָלִים לֶב גִּבּוֹרִים קֶשֶׁת יְהוֹנָתָן וֹּא נָשׂוֹג אָחוֹר

וְחֶרֶב שָׁאוּל וֹּא תָשׁוּב רֵיקָם׃

From the blood of the slain (warriors) and the fat of the (slain) warriors, the bow of Jonathan did not turn back and the sword of Saul was not returned empty.

Here David turns to a praise of Saul and Jonathan as military heroes of Israel. As Keil and Delitzsch suggest, “The figure upon which the passage is founded is, that arrows drink the blood of the enemy, and a sword devours their flesh (vid. Deut xxxii.42; Isa xxxiv.5, 6; Jer xlvi.10).” [106]

Verse 23

שָׁאוּל וִיהוֹנָתָן הַנֶּאֱהָבִים וְהַנְּעִימִם בְּחַיֵּיהֶם וּבְמוֹתָם וֹּא נִפְרָדוּ

מִנְּשָׁרִים קַלּוּ אֲרָיוֹת גָּרוּ׃

Saul and Jonathan, loved and lovely, in their lives and in their deaths they were not separated. They are swifter than eagles, stronger than lions.

Keil and Delitzsch note that “The light motion or swiftness of an eagle…, and the strength of a lion…, were the leading characteristics of the great heroes of antiquity.” [107] The idea of life and death is used to express the total time period of their lives. [108] The fact that Saul and Jonathan were not separated refers to more than the fact that they were slain on the same battlefield. Jonathan remained loyal to his father throughout his life in spite of his recognition that David would rule Israel, and not he. Nevertheless, even at the battle which brought his death he was faithfully at his father’s side fighting a hated foe.

Verse 24

בְּנוֹת יִשְׂרָל אֶל־שָׁאוּל בְּכֶינָה הַמַּלְבִּשְׁכֶם שָׁנִי עִם־עֲדָנִים

הַמַּעֲלֶה עֲדִי זָהָב עַל לְבוּשְׁכֶן׃

Women of Israel, weep over Saul, who clothed you with luxurious scarlet and put ornaments of gold upon your clothes.

The women of Israel are called upon to weep because of the loss of their benefactor. Weeping was the expected response to death. Kepelrud notes, “Death was followed by weeping and mourning, whether they liked the deceased or not. It was a force in itself, and the right ceremonies had to be performed.” [109]

In this verse Saul is represented as bringing a measure of prosperity to Israel. It must be recognized that while the biblical text “clearly displays anti-Saul biases,” [110] it also intimates a measure of peace and prosperity attained under Saul’s rule that had not been experienced in the prior period. Evidence for this assertion is found in the absence of Philistine control of Israel during Saul’s reign and the loyalty Saul commanded, even in the southern portions of Israel (see, e.g., 1 Sam 23:3–12, 19–20; 31:11–13; and 2 Sam 16:5–8). [111]

Verse 25

יךְ נָפְלוּ גִבֹּרִים בְּתוֹךְ הַמִּלְחָמָה

יְהוֹנָתָן עַל־בָּמוֹתֶיךָ חָלָל׃

How are the mighty fallen in the midst of the battle! Jonathan lies slain on your heights.

חלל is taken as a Qal passive as in v 19. The similarity of v 25 with v 19 and v 27 has been noted. But the structural analysis showed that v 25 was not structurally related to either of these other verses, but that it is a fake coda (i.e., a false ending). The separate treatment of Jonathan in a fake coda subtly shows David’s preference for him.

Verse 26

צַר־לִי עָלֶיךָ אָחִי יְהוֹנָתָן נָעַמְתָּ לִּי מְאֹד

נִפְלְאַתָה אַהֲבָתְךָ לִי אַהֲבַת נָשִׁים׃

It is a distress to me concerning you, my brother. Jonathan, you were very pleasant to me. You are wonderful. Your love is mine. What is the love of women?

Here David breaks out in a truly emotional lament over the loss of his friend. The last clause is difficult to translate. Generally the מ of מאהבת has been understood as comparative with the resulting translation, “your love for me is better than the love of women.” However, the above structural analysis suggests that the last part of v 26 consists of three independent verbless clauses. This rules out the use of מ as a comparative. Therefore, the מ should be understood as an interrogative (an abbreviation of מה).

As noted in the structural analysis, O’Connor believes v 26a-b exhibits personal binomation in which אחי is used as a title. O’Connor states, “The relationship between David and Jonathan warrants a technical reading of the term ʾḥ ‘brother,’ in view both of their covenanting and of David’s later protection of Jonathan’s son.” [112] The covenantal force of the term can be seen in its use describing the relationship between rulers (e.g., 1 Kgs 9:13) and between nations (e.g., Num 20:14).

Verse 27

יךְ נָפְלוּ גִבּוֹרִים וַיֹּאבְדוּ כְּי מִלְחָמָה׃

How are the mighty fallen! They are perished, the instruments of war.

The “instruments of war” have been generally understood as referring to Saul and Jonathan themselves. [113] Thus, the last line of the lament refocuses attention on the subjects of and the reason for the lament.

Literary Setting

The books of Joshua through 2 Kings are known as the “Former Prophets.” This characterization of these books is somewhat curious. Prophetical material is normally associated by Christians with such books as Isaiah or Daniel, or the Minor Prophets, and so on. On the other hand, the Joshua-Kings narrative reads as history. Perhaps the title “Former Prophets” arose because of the belief that these anonymously written works were in fact written by prophets. [114] Be that as it may, the title does indeed characterize the content of these books, performing the prophetic task of revealing God’s will and word to man.

The prophetical and historical nature of Joshua-Kings coalesces in the selection and interpretation of the details used in recording “what happened.” Martin Noth has called this narrative a “deuteronomistic history.” [115] To Noth this term referred to a reworking of historical traditions (and of the original “Deuteronomy”) by a redactor (or group of redactors) to form a unified theological history of the nation of Israel from the period of the Conquest to the Babylonian Captivity. With a slight modification, Noth’s theory seems to capture the organizing principle of the Joshua-Kings narrative. Noth denied the authenticity of the present Deuteronomy as Mosaic. However, a reinterpretation of his basic insight allows one to see the Joshua-Kings narrative as a “later and deliberate modeling upon a literally Mosaic Deuteronomy.” [116] With this readjustment of Noth’s premises, his statement of the central theological theme of the narrative is valuable. He says,

The meaning which [the deuteronomist] discovered was that God was recognisably at work in this history, continuously meeting the accelerating moral decline with warnings and punishments and, finally, when these proved fruitless, with total annihilation. Dtr., then, perceives a just divine retribution in the history of the people, though not so much (as yet) in the fate of the individual. [117]The question at hand, then, is “How does David’s Lament contribute to the development of the central theme in the Joshua-Kings narrative?” A step in the direction of answering this question may be taken by comparing the narrative surrounding the Lament with the other OT narrative dealing with the history of Israel in the time of Saul and David. That narrative is, of course, Chronicles. A comparison of the Hebrew texts of 1 Sam 31:1-2 Sam 5:3 and 1 Chron 10:1–11:3 reveals some interesting facts. There is almost exact verbal agreement found between 1 Sam 31:1–13 and 1 Chron 10:1–12. [118] The text in Chronicles then adds the editorial comment,

Saul died because he was unfaithful to the LORD; he did not keep the word of the LORD and even consulted a medium for guidance, and did not inquire of the LORD. So the LORD put him to death and turned the kingdom over to David son of Jesse (1 Chron 10:13–14).The Chronicler then resumes his account with a passage that is almost word for word the same as 2 Sam 5:1–3. [119] The near perfect verbal agreement gives evidence that the Chronicler had access to a text of the Samuel narrative when he compiled his account. However, he omitted entirely the content of 2 Samuel 1–4.

There are a couple of inferences that can be drawn from these facts. Hummel notes,

The public, corporate concern of the variations [of Chronicles compared to Samuel/Kings] seems established by the fact that nearly everything of the private lives of David and Solomon is omitted, not only what might possibly besmirch their reputation (as critics often construe it), but also episodes which might have contributed to an idealized portrait. [120]By inference it may be argued that the Samuel-Kings narrative is concerned with the private lives of these men. This coincides with the deuteronomistic styling of the Joshua-Kings narrative. Even a cursory reading of this narrative reveals that as went the leaders of the nation (i.e., either following Yahweh or not), so went the nation. Thus, the narrative is concerned with the personal qualities of David as the leader of the nation: do his qualities merit Yahweh’s blessing for the nation? The answer to this question, at least until David’s sin with Bathsheba, is “Yes.” The text is careful to show that David is no mere usurper to the throne of Israel. David purposefully avoided killing king Saul on two occasions (1 Samuel 24, 26). When the report came that Saul had been killed, David put to death the messenger who claimed to have inflicted the final blow (2 Sam 1:14–16; cf. 2 Sam 4:10). David rewarded the men who had risked their lives to bury Saul (2 Sam 2:4–7). David disclaimed any part in the murder of Abner, the commander of Saul’s army who initially served Ish-Bosheth, Saul’s son and successor (2 Sam 3:28–29). And finally, David put to death the men who killed Ish-Bosheth himself (2 Samuel 4). David’s Lament contributes to this portrait of David as a man who did not seek his own, but waited on the hand of Yahweh.

A second inference that can be drawn from a comparison of the account in Samuel with the account in Chronicles concerns the right to rule over Israel. The historical account in Chronicles of Saul’s rule over Israel begins with Saul’s death! The kings of the Northern Kingdom are never treated in Chronicles as having a legitimate right to rule. The Northern kings are never given the title “King of Israel,” but this title is consistently applied to the kings of Judah. Perhaps the Chronicler, from his historical perspective, does this to reinforce the underlying unity of the kingdom and the right of Davidic rule. The Samuel-Kings narrative, however, presents a more accurate picture of the political realities during this period. With this difference between the two accounts in mind, the actions of David (as noted above) can legitimately be read in another light (and not be contradictory to the assertions made above). There are indications in the narrative that Saul commanded a great deal of respect from his subjects, in the South as well as the North. As Evans notes,

faced with the external military threat and the internal political threat posed by a pretender, [Saul] is an effective military leader despite his emotional affliction. He is succeeded by his son, and the pretender to the northern throne is forced to play a careful political game before he is able to take over Saul’s home territory. Even then, strong pro-Saul and anti-David feelings are manifested by curse and later by open rebellion against David. [121]The notion that David had to woo the leadership of the nation to his side is reinforced by his action recorded in 1 Sam 30:26—following his defeat of the Amalekites he sent plunder to the elders of Judah.

One final note may be added about the characteristics of the Joshua-Kings narrative as it relates to David’s Lament. It seems that in this narrative, the relative good of those who are otherwise disobedient to Yahweh is credited to their account (cf. 2 Kgs 10:30–31). Thus the Lament is a fitting tribute to Saul, the “tragic hero.” [122]

To summarize, in its literary setting, David’s Lament can be read on a number of levels. First, it contributes to an idealized picture of David as a king whose obedience Yahweh may bless. Second, as part of a series of actions, it contributes to a realistic picture of how David came to accede to the throne of Israel. And finally, it softens the picture of Saul, crediting him for the effective leadership he did provide for Israel.

Conclusion

It is hoped that by now the reader has gained an appreciation for both the problems and the beauty of David’s lament over the deaths of Saul and Jonathan. I have been reminded once again through this study of the integral part human emotions have in the life of man. Driver wrote of this lament,

There breathes throughout a spirit of generous admiration for Saul, and of deep and pure affection for Jonathan: the bravery of both heroes, the benefits conferred by Saul upon his people, the personal gifts possessed by Jonathan, are commemorated by the poet in beautiful and pathetic language. It is remarkable that no religious thought of any kind appears in the poem: the feeling expressed by it is purely human. [123]Emotion is not detached from the world in which man is placed. Human emotion may reflect a character pleasing to God (as seen here in the life of David), or a character not in harmony with him. And the display of that emotion may either move his purposes forward (as in the establishment of David’s rule over Israel through his respect for Saul), or run against the grain of his purposes.

Appendix

Notes

- William L. Holladay, “Form and Word-Play in David’s Lament over Saul and Jonathan,” VT 20 (1970) 154.

- C. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Books of Samuel, trans. James Martin (vol. 2 in Commentary on the Old Testament; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975 [reprint]) 288.

- Stanley Gevirtz, Patterns in the Early Poetry of Israel, 2d ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1973) 73.

- Peter R. Ackroyd, The Second Book of Samuel (The Cambridge Bible Commentary; Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1977) 24.

- Hans Wilhelm Hertzberg, I & II Samuel, 2d ed. (The Old Testament Library; Philadelphia: Westminster, 1960) 238.

- Gevirtz (Patterns, 72–96) and Holladay (“Form and Word-Play,” 153–89) are extreme examples.

- M. O’Connor (Hebrew Verse Structure [Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1980]) chose 2 Sam 1:19–27 as a key text for demonstrating his analysis of the structure of Hebrew poetry. D. N. Freedman (“The Refrain in David’s Lament over Saul and Jonathan,” Ex Orbe Religionum: Studia Geo Widengren, Studies in the History of Religions/Supplements to Numen 21 [Leiden: Brill, 1972] 115-26) has a detailed discussion on the metrical structure of these verses. Gevirtz (Patterns) and Holladay (“Form and Word-Play”) use structural analysis as the basis for their reconstructions of the text.

- Hertzberg, I& II Samuel, 238.

- Holladay, “Form and Word-Play,” 154.

- Gevirtz, Patterns, 72 (see his documentation in n. 4).

- Henry Preserved Smith, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Books of Samuel, 2d ed. (ICC; Edinburg: Clark, 1912) 258. However, note that Smith distrusts the received text and offers several emendations.

- Cf. the remarks by Hertzberg, I & II Samuel, 238.

- All quotations from the Hebrew OT in this article are from A. Alt et al., eds., Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung, 1977).

- It is interesting to note that while the battle which was to result in Saul’s death was being set in array, David engaged in combat and defeated a band of Amalekites who had raided his base at Ziklag. Thus, the same people who had figured so prominently in Saul’s downfall (1 Samuel 15) also played an important part in David’s rise to power (1 Samuel 30; note esp. v 26 which records David’s action of sending some of the plunder from this victory to the elders of Judah—part of his strategy to woo their support).

- Christian E. Hauer, Jr. (“The Shape of the Saulide Strategy,” CBQ 31 [1969] 153-67, esp. 163-67) argues that this battle was a result of initiative taken by Saul as the third stage of a strategic pattern to secure the boundaries of the emerging Israelite monarchy.

- Gevirtz, Patterns, 73.

- A comparison of Codex Leningrad B 19A (Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographa Codex Leningrad B 19A, vol. 2 [Jerusalem: Makor, n.d.) 96) and the Aleppo Codex (Moshe H. Goshen-Gottstein, ed., The Aleppo Codex Provided with massoretic notes and pointed by Aaron Ben Asher [Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1976] 110-12) yielded no differences in reading and the same text is recorded in BHS. For the purposes of this article, therefore, the text of BHS will be assumed to be the same as the MT.

- Holladay, “Form and Word-Play,” 155. Holladay continues, “some of the emendations suggested during this period of critical study are of permanent value.” Holladay assumes the corruption of the MT and follows at most points the reconstruction of the text offered by Gevirtz (Patterns in the Early Poetry qf Israel [Chicago: University of Chicago, 1963] 72-96) but adds a few “improvements.”

- Smith, The Books of Samuel, 259. While this is an extreme example, most commentators suggest at least some emendation to the text.

- Gevirtz’s whole section on 2 Sam 1:17–27 (Patterns, 72–96) is largely devoted to “reconstructing” a comprehensible text. Holladay (“Form and Word-Play,” 153–89) “improves” Gevirtz’s work based on “word-play” (which he defines as “any likeness of sound between two words or phrases, whether it is deliberate punning of names, or assonance of any sort” [p. 157]). This feature, he says, is exhibited in the early laments of Israel (ibid., 156).

- The following versions were used: Alfred Rahlfs, ed., Septuaginta (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung, 1935); Alexander Sperber, ed., The Bible in Aramaic, vol. 2, The Former Prophets according to Targum Jonathan (Leiden: Brill, 1959); and Bonifatio Fischer et al., eds., Biblia Sacra luxta Vulgatam Versionem (Stuttgart: Württembergische Bibelanstalt, 1969).

- For less extensive emendations see Smith, The Books of Samuel, 259–60 and S. R. Driver, Notes on the Hebrew Text and the Topography of the Books of Samuel (Oxford: Clarendon, 1913) 233-34.

- Gevirtz, Patterns, 76 (but see my translation below, p. 116). Gevirtz says of קשת, “it is…likely that קשת is to be read, not with the vocalization of the Massoretic text as קָשֶׁת (pausal form of קֶשֶׁת), ‘bow,’ but as קְשַׁת, construct form of the adjective קָשֶׁת, ‘hard,’ ‘severe’“ (ibid).

- See the argument presented by A. R. Millard, “‘Scriptio Continua’ in Early Hebrew: Ancient Practice or Modern Surmise,” JSS 15 (1970) 2-15. In this article Millard argues against solving “textual problems in the Old Testament…by redividing the traditional sequence of letters on the grounds that the words would not have been separated in ancient times” (p. 2). He offers an impressive array of evidence from various sources to establish the fact that “word-division was normal amongst the majority of West-Semitic scribes” (p. 12) and that “The absence of division from various texts…should be the exceptions that prove the rule” (p. 13).

- Gevirtz, Patterns, 76.

- H. L. Ginsberg, “A Ugaritic Parallel to 2 Sam 1:21, ” JBL 58 (1938) 209-13.

- See, e.g., Gevirtz, Patterns, 85–87; Holladay, “Form and Word-Play,” 170–71 (although he suggests the plural שרעי for Ginsberg’s singular שרע); Robert Gordis, The Word and the Book (New York: KTAV, 1976) 35-36; T. L. Fenton, “Ugaritica—Biblica,” in Ugarit-Forschungen, Band I (Butzon & Bercker Kevelaer, 1969) 67-68; and T. L. Fenton, “Comparative Evidence in Textual Study: M. Dahood on 2 Samuel i 21 and CTA 19 (1 Aqht), 1, 44–45, ” VT 29 (1979) 162-70.

- Smith, The Books of Samuel, 262.

- John Mauchline, 1 and 2 Samuel (New Century Bible; Greenwood: Attic, 1971) 200.

- See the chart in E. Kautzsch and A. E. Cowley, Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar, 2d ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1910 [reprint, 1980] xvii, which gives examples of how Hebrew letters were formed in various periods.

- Cf. Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Oxford: Clarendon, 1953 [reprint]) 810. See Ps 118:23 (Hebrew).

- Holladay, “Form and Word-Play,” 183.

- Frank Moore Cross and David Noel Freedman, Studies in Yahwistic Poetry (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1975) 26. This suggestion is followed by O’Connor, Hebrew Verse Structure, 233. Earlier Freedman (“The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 123) had stated more forcefully, “The omission…may have been the result of accidental haplography. More likely the omission was deliberate.”

- See the discussion by I. O. Lehman, “A Forgotten Principle of Biblical Textual Tradition Rediscovered,” JNES 26 (1967) 93-101. Lehman cites numerous examples from extra-massoretic texts, Aramaic and Samaritan traditions, the Peshitta, Biblical Greek, and Biblical Hebrew to show that the principle of “textual ambivalence of Hebrew consonants” (i.e., “the same consonants may be connected both with the word preceding and that following it” [p. 93]) existed in the ancient Near East. Mitchell Dahood (Psalms, vol. 2 [AB; Garden City: Doubleday, 1968] 81) agrees with this principle and cites additional references. He also cites some bibliographic references to show that the idea is not new with Lehman. A somewhat contrary position is taken by Millard, “‘Scriptio Continua,’“ 2–15 (see above, n. 24). However, Millard’s contention that it was the normal scribal practice to divide words does not necessarily militate against the position espoused by Lehman. Indeed, Millard recognizes cases where words were not normally separated (see p. 15), and the situation described by Lehman may be such a case.

- Many emendations that have been suggested have not been mentioned in this discussion. Those not mentioned are either insignificant or have almost no basis for acceptance.

- BDB, 839–40. Cf. William L. Holladay, A Concise Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1971 [reprint, 1980]) 302; Reuben Alcalay, The Complete Hebrew-English Dictionary (Hartford: Prayer Book, 1965) 2147; and Avraham Even-Shoshan, הַמִּלּוֹן הֶחָדָשׁ, vol. 5 (Jerusalem: Kiryath Sefer, 1979 [Hebrew]) 1295 (2 Sam 1:19 is cited as sn example meaning פְּר “glory,” יֹפִי “beauty,” הָדָר “splendor”).

- Marcus Jastrow, A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmudi Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature (New York: Judaica, 1975) 1128.

- Holladay, “Form and Word-Play,” 165.

- BDB, 662.

- Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, revised by Henry Stuart Jones and Roderick McKenzie (Oxford: Clarendon, 1940 [reprint, 1977]) 1644.

- BDB, 662.

- Edwin B. Levine, Goodwin B. Beach, and Vittore E. Bocchetta, eds., Latin Dictionary (Chicago and New York: Follett, 1967) 173.

- V 19a: הצבי ישראל על־במותיך חלל V 25b: יהונתן על־במותיך חלל.

- O’Connor, Hebrew Verse Structure, 471.

- R. Laird Harris; Gleason L. Archer, Jr.; and Bruce K. Waltke, eds., Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, vol. 2 (Chicago: Moody, 1980) 1869-70.

- Mauchline, 1 and 2 Samuel, 199. See also Keil and Delitzsch, Second Samuel, 290.

- Freedman, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 119–20. On the term ẓby, “gazelle,” in Ugaritic see Cyrus H. Gordon, Ugaritic Textbook (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1965) 407, entry 1045.

- Freedman, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 120. In this identification he is followed by William H. Shea, “David’s Lament,” BASOR 221 (1976) 141, and O’Connor, Hebrew Verse Structure, 231. O’Connor notes that F. M. Cross and D. K. Stuart identified the Gazelle as Saul.

- George Arthur Butrick, ed., The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, vol. 1 (New York: Abingdon, 1962) 358.

- Freedman, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 119.

- Cf. the remarks of O’Connor recorded below, p. 115.

- Cf. BDB, 119.

- Gevirtz, Patterns, 77.

- Ibid., 78.

- Ibid., 77-81, esp. 81. On the last point, cf. Kautzsch and Cowley, Hebrew Grammar, 415, §128d.

- Cf. BDB, 119, s.v. במה, 1 and 2.

- On the suggested emendations to alleviate the difficulties of this term, see the discussion above, pp. 102-3.

- BDB, 929.

- Holladay, Lexicon, 395. Cf. Alcalay (Hebrew-English Dictionary, 2846), who lists the meanings “offering, gift, donation; contribution; oblation” and associates Terumah with the priestly tithe on produce.

- Keil and Delitzsch, Second Samuel, 290.

- Freedman, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 122. In this he is followed by Shea, “David’s Lament,” 141.

- J. P. Fokkelman, “שדי תרומת in II Sam 1 21a —a non-existent crux,” ZAW 91 (1979) 290.

- Freedman, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 122. On this basis Freedman must insist that the use of בלי in v 21b is assertive, rather than the normal use of this term as a poetic negative particle. However, neither Kautzsch and Cowley (Hebrew Grammar, 481, §152g[f,g]) or Ronald J. Williams (Hebrew Syntax: An Outline, 2d ed. [Toronto: University of Toronto, 1976] 68-69, §417–20) recognize such a use.

- Shea, “David’s Lament,” 142, n. 5.

- Holladay, “Form and Word-Play,” 188. Note that Holladay makes these remarks on the basis of his “reconstruction” of the Hebrew text. Nevertheless, his remarks are also appropriate for the MT text as it stands.

- Smith, The Books of Samuel, 260.

- Driver, Notes on the Hebrew Text, 234.

- Note that both Gevirtz (Patterns, 72–96) and Holladay (“Form and Word-Play,” 153–89) have extensive discussions on the structure of 2 Samuel 1 beginning with v 18. However, their discussion is omitted from consideration here because they do not discuss the structure of the MT text, but the structure of their “reconstructed” text.

- Shea, “David’s Lament,” 143.

- Freedman, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 126.

- Ibid.

- O’Connor uses the term “stave” to denote the largest poetical unit in Hebrew poetry which normally consists of 23 to 31 lines according to his analysis. He uses the term “batch” to refer to a small unit of 5 to 8 lines, which under unusual circumstances may vary from 1 to 12 lines. A final term he uses in his description of poetic units is “burden.” A burden is a refrain structure of 2 to 8 lines containing fixed (i.e., repeated in each occurrence of the burden) and free (i.e., non-repeated) lines. See O’Connor, Hebrew Verse Structure, 527–33.

- Ibid., 468-71.

- O’Connor (ibid., 4–5) notes that the strictures were recognized by Lowth in what has been the standard description of Hebrew poetry. Lowth termed these two strictures meter (which he considered hopelessly lost to the modern reader) and parallelism. O’Connor believes that Lowth’s crucial insight was not the discovery of parallelism, but the realization “that parallelistic phenomena alone cannot suffice to describe Hebrew verse; something else is going on, which Lowth called meter” and the realization that these two phenomena are interacting. O’Connor’s book, Hebrew Verse Structure, is his attempt to refine the understanding of these two strictures and their interaction. O’Connor argues that the regularities Lowth regarded as phonological and called “meter” are in fact syntactic. Thus, he subjects the text to intensive linguistic analysis. The other factor in Lowth’s description, loosely known as parallelism, O’Connor expands and refines by outlining various “tropes” or figures of speech found in Hebrew poetry.

- For an explanation of these terms see ibid., 87–137.

- Ibid., 421.

- Ibid., 376.

- Ibid., 384.

- On the use of the construct form, הרי, as a vocative, see below, p. 118.

- Cf. Freedman, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 122 and O’Connor, Hebrew Verse Structure, 231.

- Ibid., 422.

- A construct noun with its genitive is taken as one constituent (e.g., קשת יהונתן), as is the negative with the verb. The plural subject in v 23a is also taken as a single constituent. My analysis of v 23a-b is contra O’Connor (ibid., 329,334), who sees these lines as consisting of two constituents.

- Note the ן for the ם of the MT. See discussion of this emendation above, p. 103.

- Ibid., 374-75.

- On אח as a title, see below, p. 121.

- The constituents of the last line are the interrogative מ and the construct-genitive chain אהבת נשים.

- Ibid., 471.

- Cf. Ackroyd, Second Samuel, 25.

- Eileen F. Deward, “Mourning Customs in 1, 2 Samuel,” Journal of Jewish Studies 23 (1972) 17.

- Cross and Freedman, Studies in Yahwistic Poetry, 6. For the metrical analysis of Freedman see his work, “The Refrain in David’s Lament,” 124–27.

- Keil and Delitzsch, Second Samuel, 288.

- Hertzberg, I & II Samuel, 238–39.

- The LXX does not refer to this book in Josh 10:13. In 2 Sam 1:18 it translates ישר with εὐθοῦς. 1 Kgs 8:53 in the LXX has βιβλίῳ τῆς ᾠδῆς, “Book of songs,” which is generally assumed to refer to the same collection.

- Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, vol. 2, 803.

- BDB, 449.

- O’Connor, Hebrew Verse Structure, 231.

- Kautzsch and Cowley, Hebrew Grammar, 471 (§148a, b).

- Hauer, “Saulide Strategy,” 153–54.

- Ibid., 166-67, n. 45.

- Kautzsch and Cowley, Hebrew Grammar, 421 (§130a).

- See the remarks of Ackroyd, Second Samuel, 26.

- Fenton, “Ugaritica-Biblica,” 68.

- Shea, “David’s Lament,” 141–42.

- BDB, 171.#

- Cf. A. R. Millard, “Saul’s Shield not Anointed with Oil,” BASOR 230 (1978) 70.

- Keil and Delitzsch, Second Samuel, 291.

- Ibid.

- Cf. Ackroyd, Second Samuel, 27.

- Arvid S. Kapelrud, The Violent Goddess: Anat in the Ras Shamra Texts (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1969) 81.

- William E. Evans, “An Historical Reconstruction of the Emergence of Israelite Kingship and the Reign of Saul,” in Scripture in Context II, William W. Hallo, James C. Moyer, and Leo G. Perdue, eds. (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1983) 77.

- Cf. ibid., 71–72, 77. See also Hauer, “Saulide Strategy,” 161.

- O’Connor, Hebrew Verse Structure, 375.

- See, e.g., Keil and Delitzsch, Second Samuel, 292; Smith, The Books of Samuel, 264; and Driver, Notes on the Hebrew Text, 239. For a contrary view see Mauchline, 1 and 2 Samuel, 201.

- Cf. R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969) 664.

- Martin Noth, The Deuteronomistic History (JSOT Supplement Series 15; Sheffield, JSOT Press, 1981).

- Horace D. Hummel, The Word Becoming Flesh (St. Louis: Concordia, 1979) 110.

- Noth, The Deuteronomistic History, 89.

- This can easily be seen in Abba Bendavid, Parallels in the Bible (Jerusalem: Carta, 1972) 30-31.

- See ibid., 35–36.

- Hummel, The Word Becoming Flesh, 623.

- Evans, “The Emergence of Israelite Kingship,” 77.