AN ESSAY BY Benjamin L. Gladd

DEFINITION

Biblical history is divided up into two distinct ages: the age of promise, when God promises to make all things right by establishing his kingdom and rule through his Messiah, and the age of fulfillment, which is the age when God’s promises are fulfilled, in which Christians are now living, and which will continue on forever.

SUMMARY

Biblical history is divided up into two distinct ages: the age of promise, when God promised to make all things right by establishing his kingdom and rule through his Messiah, and the age of fulfillment, when God’s promises are fulfilled. The Old Testament prophets talked about the age of fulfillment as the “latter days”. While they expected these latter days to come with the Messiah at the end of much tribulation and suffering, the New Testament authors tell us that these days have intruded into history earlier than that with the coming of Jesus Christ. Now, we live in the overlap of these ages, in the “already-not yet”—the age of fulfillment, the latter days, having come “already” with the kingdom of God through Jesus Christ, and the age of promise, with its accompanying suffering and tribulation, still remaining until the second coming of Messiah Jesus.

------------A Better Eden

The phrase “two ages” refers to two distinct epochs of biblical history. The first epoch could be considered the period of “promises”—God promises to dwell with his people, bring about the arrival of the messiah, establish the kingdom, offer forgiveness of sin, raise the saints from the dead, and so forth. The second epoch is the age of fulfillment and takes place during the period known as the “latter days” or the “end times.” There is where eschatology comes to the fore. Our English term “eschatology” comes from two Greek words: eschatos (“last”) and logos (“word”). So, eschatology is the “study of the last things.” We should consider the final phase of redemption to be “eschatological,” as it takes place at the very end of history. The Old Testament uses the phrase “latter days” or the “last days” to refer to this final period of Israel’s history (e.g., Gen. 49:1; Num. 24:14; Dan. 2:28–29, 45). All the events that take place within this period, whether acts of judgment or restoration, are “eschatological.”

Though some believe that these two ages can only be discerned in the latter portion of the Old Testament, we can find evidence of eschatology in Genesis 1–3. While creation is deemed “good” (Gen. 1:3, 10, 18, 21, 25) and Adam and Eve “very good” (Gen. 1:31), there remains an element of incompleteness. For example, Adam and Eve, while perfectly fashioned in God’s image, can still sin. Sin can still invade the created order, too. Lastly, God created the cosmos to be a gigantic, cosmic temple so he can move in and dwell intimately with it. If Adam and Eve obey God’s commission in 1:28 and his law in 2:16–17 by producing godly descendants, expanding the boundaries of Eden and filling the earth with God’s glory, keeping his commands, and subduing evil, then the earth would be transformed into an incorruptible creation, evil would be abolished, and humanity would inherit incorruptible bodies. God would descend to earth to rule and dwell with humanity for all of eternity. Those are future realities contingent upon perfect obedience. That is the expectation of Genesis 1–2.

Those expectations are very much related to what will transpire in the “latter days.” Like a seed germinating, sprouting, and eventually growing into a tree, the Old Testament writings begin with an eschatological seed in Genesis 1–3 and then develop into a vast tree by the close of the canon. The period of the “latter days” is not unrelated or disconnected to the rest of the Old Testament. It is the climax of Israel’s story.

A Better Promised Land

The Old Testament writers and prophets foresaw a time when the final redemption of God’s people and creation would emerge. This second epoch or age in Israel’s career was to take place at the end of history. This period is an irreversible break with the events that preceding. The Old Testament does not give us a line-by-line account of how the events will unfold. The Old Testament prophets tend to leave out elements depending upon the aim of their oracles. Nevertheless, a broad outline of what will transpire in the “latter days” is clear enough:

- Israel will endure a period of intense suffering and affliction instigated by an end-time opponent. This antagonist will deceive many within Israel and persecute those who do not succumb to his false teaching (Dan. 11:31–35).

- God will vanquish Israel’s enemies through a descendant of David, the messiah (Gen. 3:15; 2 Sam. 7:13; Ps. 2:8–9).

- Those persecuted and martyred because of their faithfulness to God’s law will be resurrected with incorruptible bodies and will rule with the messiah in his eternal kingdom (Isa. 25:8; Ezek. 37:12–13; Dan 12:1-3) and in his new temple (Ezek. 40–48).

- God will transform the present cosmos into an incorruptible one, the new heavens and earth, that will house God and redeemed humanity (Isa. 65:17; 66:22).

- God will cut a new covenant with restored Israel and the nations and pour out his Spirit on them (Jer. 31:33–34; Ezek. 36:26–27; Joel 2:28–29).

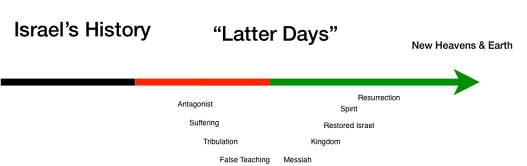

Thus, the “latter days” entail positive and negative elements with the negative elements generally preceding the positive. We can graphically depict the Old Testament’s expectation of the end of history:

God first judges then restores. At that point, God will descend from heaven and dwell with redeemed humanity in the new creation for all of eternity.

The Overlap of the Ages in the New Testament

One of the most striking dimensions of the New Testament is the apostles’s insistence that the “latter days” have broken into history. Each New Testament book, in some way, claims that the last epoch in Israel’s history has begun through the person of Christ. All that the Old Testament foresaw would occur in the end times has begun to be fulfilled in the first coming of Christ and continues until the second coming of Christ. The Old Testament end-time expectations of the great tribulation, God’s subjugation of the Gentiles, deliverance of Israel from oppressors, Israel’s restoration and resurrection, the new covenant, the promised Spirit, the new creation, the new temple, a messianic king, and the establishment of God’s kingdom have all been set in motion through Christ’s death and resurrection.

The expression “already-not yet” refers to two stages of the fulfillment of the latter days. It is “already” because the latter days have dawned in Christ, but it is “not yet” since the latter days have not consummately arrived. Scholars often use the phrase “inaugurated eschatology” or overlap of the ages to describe this phenomenon. The New Testament outlines the following schema of fulfillment:

We will briefly examine two dimensions of the already-not yet—the kingdom of God and the presence of the antichrist.

The Inauguration of the End-Time Kingdom

Much of what Jesus says in the Gospels is centered upon the establishment of the end-time kingdom, an event that, according to the Old Testament, was to take place at the very end of history. Jesus argues that the kingdom has indeed arrived, but his followers and the crowds struggled to believe Jesus’s staggering claims. Central to this discussion is Jesus’s claim that the disciples have received the “mysteries of the kingdom” (Matt. 13:11; Mark 4:11; Luke 8:10). The term “mystery” originates in the book of Daniel, especially chapters 2 and 4, where it concerns judgment upon pagan nations and the establishment of God’s end-time kingdom. Nebuchadnezzar dreamed about a colossus with four parts, and each part represented four pagan kingdoms (Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome). A “stone” then smashed the statue and eventually filled the entire earth, illustrating that the whole earth was filled with God’s kingdom (Dan. 2:29–35). The prophet Daniel interpreted the meaning of Nebuchadnezzar’s symbolic dream (Dan. 2:36–45). Nebuchadnezzar’s dream and Daniel’s interpretation of it constitute the “mystery.” The divine revelation is thus “hidden” (Nebuchadnezzar) but later “revealed” (Daniel). “Mystery” then becomes a framework for understanding revelation that generally refers to a teaching or doctrine that entails new or surprising elements.

What does Jesus mean by the “mystery of the kingdom of God”? In the immediate context of Matthew 13, the “mystery” is related to the parable of the sower and the following parables concerning the kingdom. The Old Testament prophecies expected the establishment of the end-time kingdom to be a decisive overthrow of God’s enemies at one consummate point at the very end of world history (e. g., Gen. 49:9–10; Num. 24:14–19; Dan. 2:35, 44–45).

What makes Jesus’s teaching about the kingdom a “mystery” is the contrast with the Old Testament expectation of the kingdom. One of the main tenets of the prophesied latter-day kingdom is the consummate establishment of God’s kingdom directly preceded by the ultimate destruction of unrighteousness and foreign oppression. The advent of the Messiah would signal the death knell of evil empires. Pagan kings and their kingdoms were to be destroyed or “crushed” (Dan. 2:44). Such a defeat and judgment would be decisive and happen all at once at the end point of history. But Jesus claims that the advent of the Messiah and the latter-day kingdom does not happen all at once. Paradoxically, two realms coexist simultaneously—those who belong to the kingdom and those who belong to the “evil one.” The kingdom has been inaugurated but remains to be consummately fulfilled. The two ages mysteriously overlap.

The Mysterious Presence of the Antichrist

The two ages are very much on Paul’s mind in 2 Thessalonians 2:5–8: “Don’t you remember that when I was still with you I told you about this? And you know what currently restrains him [the man of lawlessness], so that he will be revealed in his time. For the mystery of lawlessness is already at work, but the one now restraining will do so until he is out of the way, and then the lawless one will be revealed” (HCSB). Paul’s understanding of the end-time opponent here is largely indebted to the book of Daniel, where a ghastly figure will oppress and deceive the covenant community in the “latter days.”

According to Daniel 11, an end-time attack upon Israel will manifest itself in two ways. An opponent will persecute righteous Israelites. Daniel 11:31 says, “His armed forces will rise up to desecrate the temple fortress and will abolish the daily sacrifice. Then they will set up the abomination that causes desolation” (cf. Dan. 2:8, 11, 25; 8:9–12; Isa. 14:12–14). Here the enemy will wage war against the temple precinct and defile it by “setting up the abomination that causes desolation.” Daniel 11:33–35 further describe the attack against the “wise” within the covenant community: “Those who are wise will instruct many, though for a time they will fall by the sword or be burned or captured or plundered” (Dan. 11:33). The righteous, nevertheless, will persevere under pressure, though they will “fall” and be “refined” and “purified” (Dan. 11:32, 36; cf. 12:10). According to Daniel, Israel’s latter-day enemy will also deceive some within the Israelite community by enticing speech. His deception results in some within the covenant community “forsaking the holy covenant” (Dan. 11:30). His influence through “flattery” also extends to those “who violate the covenant” to become even more godless (Dan. 11:32), to compromise, and to foster deception and further compromise among others.

At the Olivet Discourse, Jesus, too, discusses end-time opponents of Israel using language from the book of Daniel: “Many will come in my name, claiming, ‘I am the Messiah,’ and will deceive many…and many false prophets will appear and deceive many people.” (Matt. 24:5, 11; cf. 24:23–26). Jesus envisions an antichrist figure(s) that will deceive Israel preceding the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70. In Matthew 24:5, the oppressor will be characterized by deception, claiming to be “the Messiah,” and, therefore, upsetting the faith of “many.”

In light of our brief analysis, we can now understand Paul’s admonitions to the Thessalonian community. Paul corrects the church’s confusion over the second coming of Christ. He makes it clear that Christ’s second coming has not yet occurred, since that day will be preceded by two events—“apostasy” and the unveiling of the “man of lawlessness” (2:3, NASB). Paul claims in 2:3 that Daniel’s “man of lawlessness” has not yet arrived on the scene, but, alarmingly, there is a sense in which the end-time oppressor is already on the scene (see 1 John 2:18–19). This suggestion explains the language in 2:7: “The mystery of lawlessness is already at work.” Paul is not teaching a general form of wickedness and persecution but a specific end-time deception and persecution that ought to be attributed to the church’s end-time antagonist. Paul employs “mystery” here in 2 Thessalonians 2:7 to describe a unique situation with startling ramifications: according to Daniel, the end-time persecutor will appear to the covenant community in his full bodily presence in the future, yet Paul argues that the antagonist is nevertheless “already at work” in the community. The church is to be on high alert for false teaching, so it must embrace the apostolic message of the gospel and its implications for daily living.

Christian Ethics in the Already-Not Yet

Eschatology, when properly understood, is not simply an exercise in theological speculation but fuel for Christian living. If believers are genuinely a “new creation” and part of the new heavens and earth (2 Cor. 5:17), then we possess the ability to overcome sin and temptation. Conversely, if a corporate antichrist is in our midst, then believers must devote themselves to the Bible to stave off false teaching and bear up under intense persecution.

FURTHER READING

- Benjamin L. Gladd and Matthew H. Harmon, Making All Things New: Inaugurated Eschatology for the Life of the Church

- D. A. Carson, “Partakers of the Age to Come,” in These Last Days: A Christian View of History

- G. K. Beale, A New Testament Biblical Theology: The Unfolding of the Old Testament in the New

- George Eldon Ladd, The Presence of the Future

- George Eldon Ladd, The Coming King

- Keith Mathison, “Doctrine of the Last Things: Recommended Reading”

- Sam Storms, Article on Eschatology

No comments:

Post a Comment