By Richard D. Patterson

[Liberty University, Box 20000, Lynchburg, Virginia 24506]

I. Preliminary Considerations

The prophecy of Jeremiah is beset by a twofold textual problem: (1) the nature of the textual tradition, and (2) the process of its composition. The former problem is best highlighted by comparing the Masoretic Text (MT) with that of the Septuagint (LXX). Thus, on the one hand LXX lacks about one eighth of the text found in MT, while on the other it adds about one hundred words not found in MT. LXX also knows a different arrangement of the material in places. For example, it puts chaps. 46–51 after 25:13, omits 25:14, and, after the foreign nations prophecies (which, in turn, are in a different order in LXX), it resumes the account with 25:15.[1] Interestingly enough, both the longer MT and the shorter LXX textual forms are attested in the Dead Sea Scrolls.[2]

The latter problem has several interrelated aspects, including the authorship of the book, the history of its composition, matters of literary genre and style, and the present arrangement of the prophecies.[3] This paper will deal with the canonical text of Jeremiah as finalized in MT and seek to reveal the underlying principles upon which the present arrangement of the prophecies is based.

The reason for the present arrangement of the Book of Jeremiah has long baffled Jeremiah’s interpreters. Although some have attempted to see a skeletal chronological framework around which the Jeremianic material has been arranged in accordance with similarity of subject matter,[4] current scholarly opinion tends to attribute the book’s arrangement to a process of composition of smaller units into tradition complexes based on such suggested premises as theme and literary style,[5] literary style and theological perspective,[6] theme and occasion,[7] or theme, occasion, and catchword.[8]

That a certain amount of editorial process took place is demanded by the scriptural evidence as presented in Jeremiah 36. This incident records Jehoiakim’s cutting and burning of Jeremiah’s original scroll and the subsequent rewriting of Jeremiah’s prophecies. Scholars are divided as to what material constituted the original scroll and what was subsequently penned in the new edition.[9] The specific details as to the further collecting and compilation of Jeremiah’s prophecies are developed variously by OT scholars.[10]

II. Literary Clues

This writer suggests that although a final decision as to the perimeters of the individual smaller units probably lies beyond the interpreter’s full determination, some understanding of the parameters of the present arrangement of the Book of Jeremiah as to its larger units can be discerned by (1) allowing the internal compositional parameters of the book to speak for themselves,[11] and (2) bringing to bear certain compilational principles of collection indigenous to the Semitic world.[12]

1. Compositional Parameters

Turning, then, to the Book of Jeremiah, one may see certain specific bits of information relative to its scheme of arrangement.

(1) Determining the Boundaries. First are those sections with headings that indicate the time of their composition: 3:6 is dated to the reign of Josiah; 24:1 and 29:1–3 to the second captivity of Jerusalem in the days of Jehoiakim; 26:1 to “early in the reign of Jehoiakim”; 27:1, 28:1, and 49:34 to “early in the reign of Zedekiah”; 32:1 to the tenth year of Zedekiah; 33:1 to the days of Jeremiah’s imprisonment in the Court of the Guard (cf. 37:21; 38:28); 34:1 to the time of Nebuchadnezzar’s final siege of Jerusalem; 35:1 to the reign of Jehoiakim (608–598 BC); 40:1 to the time of Jeremiah’s release by Nebuzaradan; 44:1 to the days of Jeremiah’s life in Egypt; and 51:59 to the fourth year of Zedekiah. Four other section headings are dated to the fourth year of Jehoiakim: 25:1; 36:2; 45:1; and 46:2.

Second are those headings that give the Lord’s instructions to the prophet relative to a message to be delivered in association with a certain act or place: 2:1; 4:5; 7:1; 13:1; 17:19; 18:1; 21:1; and 30:2. Third, one may note certain headings that indicate a specific subject matter that follows: 11:2 begins a section dealing with the covenant; 14:1 begins Jeremiah’s message concerning the drought; 23:9 heads a section “concerning the prophets”; and 46–51 is introduced with the notice that “this is the word of the LORD that came to Jeremiah the prophet concerning the nations” (46:1).

It is evident that all such data delineate the beginning of an original or collected unit of Jeremianic material. They do not necessarily yield a clue as to the end of that unit nor the individual segments that make up the unit, but at least they do give information as to where the unit, thus formed by whatever process of compilation, begins. A further comparison and collation of these data, however, suggests that within the larger collection the following sections of material can be found: 2:1–3:5; 3:6–4:4; 4:5–6:30; 7:1–10:25; 11:1–12:17; 13:1–27; 14:1–17:18; 17:19–27; 18:1–23; 19:1–20:18; 21:1–14; 22:1–23:8; 23:9–40; 24:1–10; 25:1–38; 26:1–24; 27:1–22; 28:1–17; 29:1–32; 30:1–31:40; 32:1–44; 33:1–26; 34:1–7; 34:8–22; 35:1–19; 36:1–32; 37:1–39:18; 40:1–43:13; 44:1–30; 45:1–5; 46:1–51:58; 51:59–64. To these may be safely added Jeremiah’s call (chap. 1) and the historical appendix (chap. 52).

As for the order of these portions, since they are manifestly out of strict chronological sequence, other bases of organization and compilation need to be considered.[13] It seems highly unlikely that purely literary or stylistic considerations alone can suffice either. For although the book does show evidence of some basic groupings, nevertheless the material is not arranged consistently in accordance with such conventions.[14] Nor can theme/subject matter be the sole determining factor, for similar themes and items of subject matter (e.g. national sin, divine discipline, and judgment) cut across all portions of the book.[15] Therefore, some combination of principles must lie behind the book’s compilation and final arrangement.[16]

This writer would like to suggest that matters of literary style, theme, and subject matter, as well as the headings themselves, have all played a part in the end product. Feinberg’s caution is well taken: “It is too much, however, to conclude that the book is a hopeless maze. A book may be arranged topically rather than chronologically. Indeed, its order may be a combination of both. The difficulty of determining which method prevails calls for close research.”[17]

(2) Describing the Boundaries. An examination of the literary material as to its subject matter suggests that the sections discerned above on the basis of their headings were carefully woven into large units. The key to the final arrangement of Jeremiah’s prophecies lies in the nature of his call (chap. 1). His was a summons to be a prophet (1) to the nations of this world and to his people in the midst of those nations (1:4–12), and (2) to his own nation in particular (1:13–19). In accordance with this twofold call and commission, the prophecy of Jeremiah may be arranged broadly in two units that are inversely related to the order of his call: chaps. 2–24 deal with Jeremiah and his nation; chaps. 25–51 focus on his message to his nation in the Babylonian crisis and conclude with a section containing oracles against the foreign nations. Each of the units begins with an introductory portion stating the theme of the larger unit,[18] proceeds with prophecies that develop that theme, and closes with a portion detailing the giving of a sign (see Table 1).

Thus, the theme of the first unit (chaps. 2–24) is set forth clearly in 2:1–3:5 as the divine punishment of Jeremiah’s faithless nation. The following sections detail the coming and causes of that judgment (3:6–23:40), and the sign of the figs closes the unit. Chap. 25 initiates the second larger unit (chaps. 25–51) by giving its theme as God’s pronouncement against Judah and all the nations of this world. That theme is developed in 26:1–51:58 in three large sections of tradition complexes that deal with (1) Jeremiah’s controversial experiences in the ongoing Babylonian crisis (chaps. 26–35), (2) Jeremiah’s experiences during the siege and fall of Jerusalem and the aftermath of the war (chaps. 37–44), and (3) concludes with a collection of prophecies containing God’s program for the nations of Jeremiah’s day. The unit is, again, closed by a sign: the sign of the sunken scroll (51:59–64). It is interesting to note that just as the first major unit (chaps. 2–24) is closed by a sign, so each of the three sections of the second major unit is closed by a sign: the sign of the Rechabites (35:1–19), the sign of the Babylonian invasion of Egypt (44:29–30), and the previously mentioned sign of the sunken scroll (51:59–64).

2. Compilational Principles

The correctness of this thematic and literary overview of the completed arrangement of Jeremiah’s prophecies is reinforced by an examination of the individual sections both as to subject matter and compositional principles.

(1) Examining the Principles. Several techniques of composition known to the Semitic world can be seen to be operative in Jeremiah, such as the use of bookending, hinging, and hooking. It is not at all uncommon in the Scriptures to have certain enclosing details function as bookends to the intervening literary material. The device is well known, particularly in poetry, where similar language or sentiment is often employed on either side of a stanza to form an inclusion of material, often in a chiastic (or inverted) format.[19]

Chapters, sections, or verses may also have a hinging effect. Thus, Parunak explains,

The hinge is a transitional unit of text, independent to some degree from the larger units on either side, which has affinities with each of them and does not add significant information to that presented by its neighbors. The two larger units are joined together, not directly, but because each is joined to the hinge.[20]

A third compositional technique is also extremely common in the OT. Known as a “link” (Parunak),[21] “catchword” (Bright),[22] “stitchword” (McKane),[23] it could also be called a “hook.”[24] Cassuto observes,

The principles governing the organization of a large quantity of material according to Eastern methods are not those underlying the meticulously systematic or precisely chronological order that is normal according to European notions.

One…method, which may appear…strange…to the European mind, but which was obvious to a man of the ancient Orient, who esteemed it as an aid to memorization, was that of arranging the sections on the basis of the association of ideas or words.[25]

By this method a given catchword or idea frequently forms a common hook or link with a corresponding word or idea in an adjoining section. Although Parunak draws a technical distinction between a key word (transitional material that occurs throughout given juxtaposed units) and a link (transitional features, such as particular words, that occur at the end of one unit and the beginning of the following unit), this paper shall not make such a distinction. Thus, hooks shall be described as those grammatical or lexical features that apparently have occasioned the juxtaposing of two contiguous sections. However, Parunak will be followed as a model in distinguishing the following hooking patterns:

A/B - Where two sections are basically related by material held in common

A/ab - Where a hook indigenous to the preceding section is structurally part of the first

Ab/B - Where a hook indigenous to the succeeding section is structurally part of the first

Ab/aB - Where two hooks each common to one part appear structurally in the opposite portion, thus forming a balanced or doubly bonded hook.

(2) Exhibiting the Principles. A serious investigation of the Book of Jeremiah establishes the presence and careful application of these techniques of literary arrangement. The use of a statement of theme and the recording of a sign to bookend both of the major units of the book (2:1–3:5; 24; and 25; 51:59–64) has already been mentioned. One may note further that three of those chapters that are dated to the fourth year of Jehoiakim (25; 36; 45) are strategically placed so as to bookend two of the larger sections of chaps. 25–51. Chap. 25 presents the theme for the whole unit, while chap. 36 concludes a series of short subsections dealing with the developing controversy that Jeremiah faced in Jerusalem (chaps 6–29), as well as the measure of comfort that he supplied (chaps. 30–31) in a time of great crisis (chaps. 32–35). Chap. 36 also serves to bookend the next section (chaps. 37–44), which traces events that led up to the fall of Jerusalem (chaps. 37–39) and rehearses details relative to the reconstruction of the land and Jeremiah’s being carried into Egypt (chaps. 40–44). This section is closed by a word to Baruch (chap. 45). The mention of Baruch in both chaps. 36 and 45 provides a further bookending device for this section.

It is obvious, as well, that chap. 36 serves as a hinge to two major sections (chaps. 26–35; 37–44) within the whole second major unit of the book (chaps. 25–51). As a hinge, although it has its own independent emphasis, chap. 36 partakes of both that which precedes and that which follows. Thus, Jeremiah’s speeches concerning Israel and Judah among the nations (cf. vv 1–2) have largely been recorded in the previous section (chaps. 25–35); his words concerning Judah’s fate at the hands of the king of Babylon (cf. vv 29–31) will be placed after chap. 36 in the next section (chaps. 37–44).

Likewise, chap. 5 functions as a hinge to two major sections (chaps. 37–44; 46–51). Of distinctly independent subject matter, it nevertheless is strategically placed so as to partake of both that which precedes and that which follows. It accomplishes the former through the twin themes of disaster (44:7, 11, 23; 45:5) and escape (44:28; 45:5). It anticipates that which follows in a twofold way: (1) both chap. 45 and chap. 46 are dated to the fourth year of Jehoiakim, and (2) God’s judgment against Egypt, with which the biography of Jeremiah’s life terminates (44:9–30), is taken up immediately in 46:1–28. To recapitulate, chapters introduced by the heading “the fourth year of Jehoiakim” (25:1; 36:1; 45:1) serve to delineate larger sections within the unit 25–51. Chap. 36 serves at once both as a bookend and a hinge for the sections 25–35 and 37–45. Chap. 45 functions both as a bookend for the section 37–44 and as a hinge to sections 37–44 and 46–51.

A further reason for the placement of these pivotal chapters in their present location (and a corroborating proof of their previously noted functions) comes by observing the literary hooks that tie them to the surrounding material. In addition to the hooks just enumerated by which the hinge chap. 45 was bound to the adjacent sections, it becomes readily apparent that chaps. 25 and 36 are similarly hooked to the chapters on either side of them. Thus, chap. 25 not only serves to set the theme for the second major unit of Jeremiah’s prophecies, but is hooked to the previous chapter by the linking phrase “king of Judah” (24:8; 25:1).[26] Likewise, chap. 36 is linked to chap. 35 by the similar ideas of (1) obedience (in the case of the Rechabites, vv 10, 13, 14, 16, 18) versus disobedience (in the case of Judah and Jehoiakim), and (2) descendants (“never fail to have a man,” 35:19, versus “will have no one,” 36:30), and is tied to chap. 37 by the hooks (1) “king of Judah” and (2) the reference to Jehoiakim (36:32; 37:1).

Having seen an overview of the basic arrangement of Jeremiah on the basis of internal data and the application of known Semitic literary devices, it is necessary to ask whether we can find further reasons for the placement of the subdivisions.[27] This writer believes that the principle of hooks supplies the key. Turning to the first major unit of the book (chaps. 2–24), the following sections have been previously established: 2:1–3:5; 3:6–4:4; 4:5–6:30; 7:1–10:25; 11:1–12:17; 13:1–27; 14:1–17:18; 17:19–27; 18:1–23; 19:1–20:18; 21:1–14; 22:1–23:8; 23:9–40; and 24:1–10. Each of these subsections can be shown to have been linked together by a common hook. This may be summarized as follows:

|

Section |

Hooked via |

To Section |

Type of Hook |

|

2:1–3:5 |

Prostitution/divorce (2:20; 3:1–3; 3:6–10) |

3:6–4:4 |

A/B |

|

3:6–4:4 |

Judah and (people of) Jerusalem (4:4; 4:5, 10, 11) |

4:5–6:30[28] |

Ab/B |

|

4:4–6:30 |

Way, people (6:16, 25f., 7:2, 3) |

7:1–10:25[29] |

A/B |

|

7:1–10:25 |

Towns of Judah (10:22, 11:5) |

11:1–12:17 |

Ab/B |

|

11:1–12:17 |

House of Judah (12:14; 13:11) |

13:1–27 |

A/B |

|

13:1–27 |

Forgotten God, therefore punishment + God remembers (13:25–14:10) |

4:1–17:18 |

A/B |

|

14:1–17:18 |

Word of the Lord (17:15; 17:20) |

17:19–27[30] |

A/B |

|

17:19–27 |

Obey (17:23–24, 27; 18:10) |

18:1–20:18[31] |

A/B |

|

18:1–20:18 |

Pashur (20:1–6; 21:1) |

21:1–14 |

A/B |

|

21:1–14 |

Concerning the royal house (21:11; 22:1–2, 6, 11, 18, 24) |

22:1–23:8 |

|

|

22:1–23:8 |

False leadership vs. true (22:1–23:4; 23:9–40 vs. 23:5–8) Land, David (22:29, 30; 23:5, 8, 10) |

23:9–40[32] |

A/B |

|

23:9–40 |

People (23:33; 24:7) Land (23:10; 24:6, 8, 10) |

24:1–10 |

A/B |

As for chaps. 25–51, the earlier discussion has shown that this unit deals with Jeremiah and the nations, whereas chaps. 2–24 focused primarily upon Jeremiah’s role to his own nation. This unit is punctuated by the bookending chaps. 25, 36, and 45 and by chaps. 36 and 45, which serve as hinges for the two sections that surround them. An examination of the internal evidence has produced evidence of many smaller individual segments: 25:1–38; 26:1–24; 27:1–22; 28:1–17; 29:1–32; 30:1–31:40; 32:1–44; 33:1–26; 34:1–17; 34:8–22; 35:1–13; 36:1–32; 37:1–39:18; 40:1–43:13; 44:1–30; 45:1–5. Once again the principle of hooks corroborates the perimeters of these subsections:

|

Section |

Hooked via |

To Section |

Type of Hook |

|

25:1–38 |

Disaster (25:29, 32; 26:3, 13, 19 bis) |

26:1–24[33] |

A/B |

|

26:1–24 |

Early in the reign (26:1; 27:1; cf. 28:1) |

27:1–22 |

A/B |

|

27:1–22 |

Yoke (27:2, 8, 12; 28:2, 10, 13, 14) |

28:1–17 |

A/B |

|

28:1–17 |

False prophesying (Iron yoke 28:13–14 vs. Neck irons 29:26) |

29:1–32[34] |

A/B |

|

29:1–32 |

Restoration from captivity (Neck iron 29:26; yoke 30:8) bring back 29:10; 30:3 |

30:1–31:40 |

A/B |

|

30:1–31:40 |

Restore the fortunes (30:18; 32:44) New/everlasting covenant(31:31–34; 32:36–44) |

32:1–44 |

A/B |

|

32:1–44 |

Return from captivity/ restore fortunes (32:36–44; 33:7, 11, 26) Covenant (32:36–44; 33:21, 25) |

33:1–26[35] |

A/B |

|

33:1–26 |

Covenant (33:21, 25; 34:8) |

34:8–22[36] |

A/B |

|

34:8–22 |

Disobeyed vs. obeyed (34:17; 35:10, 13–14, 16, 18) |

35:1–19 |

A/B |

|

35:1–19 |

Never fail to have a man vs. will have no one (35:19, 36:30) Reign of Jehoiakim (35:1; 36:1) |

36:1–32 |

A/B |

|

36:1–32 |

King of Judah (36:1, 32; 37:1) Son of Josiah (36:1; 37:1) |

37:1–39:18 |

A/B |

|

37:1–39:18 |

Jeremiah's imprisonment vs. release; fall of Jerusalem vs. after fall (37:21; 38:6–10, 13, 28; 39:15; 40:1–2) |

40:1–43:13 |

A/B |

|

40:1–43:13 |

Egypt (43:7–13; 44:1ff.) |

44:1–30 |

A/B |

|

44:1–30 |

Disaster (44:7, 11, 23; 45:5) Escape (44:28; 45:5) |

45:1–5 |

A/B |

Accordingly, an examination of the literary hooks discernible in the major units reveals that the larger sections have been brought together in a general way chiefly on the basis of a closeness of theme (e.g. 2:1–3:5 and 3:6–4:4; 25:1–38 and 26:1–24; 30:1–31:40 and 32:1–44) and/or subject matter (e.g. 3:6–4:4 and 4:5–6:30; 22:1–23:8 and 23:9–40; 30:1–31:40 and 32:1–44; 32:1–44 and 33:1–26), and in nearly every case by verbal hooks that appear in close proximity.

As for the last major section of the second unit, it may be noted that beginning with the literary hook “the fourth year of Jehoiakim” the various collections of oracles are arranged geographically, dealing first with those nations that are adjacent to Israel: Egypt to the south (chap. 46),[37] Philistia to the west (chap. 47), Moab, Ammon, and Edom to the east (chap. 48; 49:1–6, 7–22), and Damascus to the north (49:23–27). The oracles that follow deal with those nations that were situated around Babylon, Kedar and Hazor to the west (49:28–33) and Elam to the east (49:34–39), and with Babylon itself (50:1–51:58). Once again the section and the whole unit is closed by a sign (51:59–64),[38]

III. Summary and Conclusions

Summary. By allowing the internal evidence in Jeremiah to speak for itself and by applying known Semitic techniques of literary arrangement, a satisfactory solution to the problem of the arrangement of Jeremiah’s prophecies can be perceived.

To recapitulate, between the introductory details of the prophet’s call and commission and the final appendix, the Book of Jeremiah shows clear evidence of compilation that formed two distinct units reflecting the prophet’s twofold commission: chaps. 2–24 and 25–51. The first unit contains oracles and pronouncements primarily concerned with bringing the Lord’s charges against his people for their continual idolatry and a catalog of the people’s sins. The second unit falls into three sections. The first of these details the growing controversy in which Jeremiah found himself with the apostate leadership of Jerusalem (chaps. 26–35). The second section chronicles the days of Jerusalem’s siege, fall, and reconstruction (chaps. 37–44). The third section contains the Lord’s oracles against the foreign nations that so often were Israel’s antagonists (chaps. 46–51). Each of the first two major units begins with the statement of its theme, proceeds with a plea to the people of God, develops the stated theme, and ends with a sign appropriate to the unit’s theme.

The design of the second unit is particularly complex, again showing the deliberate intent of its composer. Thus, three chapters serve as keys to the collection, each being dated to the fourth year of Jehoiakim: chaps. 25, 36, and 45. Although each chapter contains much individual material in its own right, each is carefully deployed so as to bookend large portions of the second unit. Chap. 36 serves as a bookend for both chaps. 25 through 35 and 37 through 45 and is a hinge for both subsections. Thus, chap. 36 also joins the first section that leads up to the time of the siege of Jerusalem (chaps. 26–35) to the details of the city’s fall and the events that followed (chaps. 37–44). As well, chap. 45 serves not only as a bookend to the previous section (chaps. 37–44) but as a hinge to the materials that surround it (chaps. 37–44; 46–51). Further internal design may be seen in that just as in the case with each of the two major units, so each of the three sections (chaps. 25–35; 37–45; 46–51) in this unit ends with a sign: the sign of the Rechabites (chap. 35), the sign of the Babylonian invasion of Egypt (44:29–30), and the sign of the sunken scroll (51:59–64). (See Table 2.)

It should be noted further that chap. 25 is strategically placed. While it functions as a bookend to both the entire unit and the first section of the unit (chaps. 26–35),[39] it is also related to the whole unit in such a way as to play a distinctive part in its context. Although the placement of chap. 25 before chaps. 26–51 makes it serve as the thematic introduction for the whole unit,40 the chapter also displays affinities with the material that precedes it.[41]

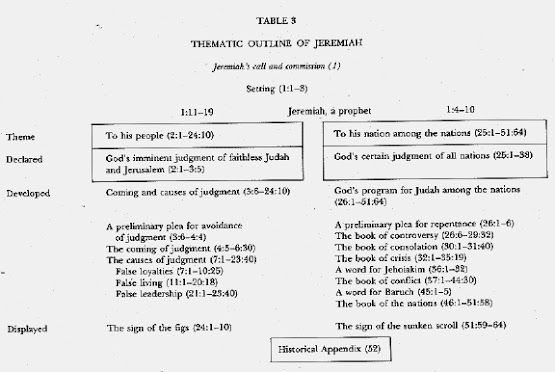

It has also been shown that not only have the major units and chief sections been woven together with deliberate precision but even the individual subsections and segments are carefully arranged so that each is linked together by a thematic or verbal hook. The results of our study may be schematized as in Table 3.

Conclusions. All of this argues for a thoughtful utilization and arrangement of the Jeremianic material. As Keil points out, “The book in its canonical form has been arranged according to a distinct, self-consistent plan, in virtue of which the preservation of chronological order has been made secondary to the principle of grouping together cognate subjects.”[42] Hobbs’ observation is a judicious caution to the excesses that have at times characterized research on the Book of Jeremiah: “…the present book of Jeremiah does possess a clear message, carefully thought out, and which cannot have been the result of the kind of ‘floating together’ of tradition complexes as envisaged by Rietzschel, and particularly by Engnell.”[43]

The result of our research, though yet preliminary, has been a beneficial one. Once the reader has grasped the principles inherent in the organization of the book, he can see Jeremiah in a positive light. Although one may not always be able to ascertain the precise occasion or time of a given oracle, section, or unit,[44] one can understand something of the reason for their placement and thus come to grips with the author’s design and intention with far more under standing. Still more benefits may yet be forthcoming. The strict application of the principle of associating passages via a system of hooks may prove to provide the interpreter with the parametric key to understanding at least in limited fashion the perimeters of still smaller individuals segments of Jeremiah’s prophecies not considered in this study.

The subjects of the authorship of Jeremiah and the history of the compilation of the book, which have been largely sidestepped in this paper, may also find real help from an application of the type of structural examination taken here. On the basis of his research, this writer is convinced that the present arrangement was made directly from four previous collected groupings that comprised what is now the following chapters: 1–24, 26–35, 37–44, and 46–51, as well as several independent chapters (25, 36, 45, and 52).[45] It would appear that the principal features of the work had by that time taken shape (e.g. theme and development, and the closing of each section with a sign), perhaps grouped around the key features of Jeremiah’s call and commission, so that it merely remained to plug in the bookend and hinge chapters at the appropriate places to achieve a unified whole.[46]

Rather that being viewed as a loose aggregate of small bits of traditional materials that somehow came together into larger complexes, both in its overall design and in its component parts from its larger units down to its smaller segments, the Book of Jeremiah displays evidence of a care and precision that can only be accounted for by the work of deliberate authorial design. The symmetry and thematic placement are far too perfect to be accidental.

Although full knowledge of the stages and precise history of the collecting and compiling of the Jeremianic material may be lacking, on the basis of this preliminary study this writer is convinced that there is nothing in the language, literary features, subject matter, or theological perspective of any part of the book, whether it is the prose or the poetry portions, whether the material is autobiographical or biographical, or whether it is the historical or sermonic sections, that cannot be attributed to Jeremiah himself or to his personal secretary, Baruch.[47] The older view of E. J. Young may yet be of merit:

There is not satisfactory reason for doubting that Jeremiah himself was the author of the entire book…. As to Baruch, all the evidence indicates that he was simply a scribe or an amanuensis, and whatever he did in the way of editing, was doubtless at Jeremiah’s direction.[48]

This study, then, underscores the importance of literary concerns to biblical exposition. Indeed, as interpreters of the Word of God our debt to literary constraints is past due. Since it is undeniably the case that God has allowed his inerrant, inspired Word to be written in accordance with known literary conventions and forms, attention to literary matters is basic to understanding properly what the Bible is saying. It needs to be emphasized repeatedly that the stool of proper hermeneutics is fashioned so as to rest on three evenly balanced legs: theology, history, and literature (including matters of lexicography, syntax, textual criticism, structure, and literary genre), the data of which are judiciously applied with full attention to the constraints of context.

The great value of giving due regard to literary considerations is not only the resultant accuracy of the conclusions reached but an increased facility in methodology that enables one to see the whole as well as the constituent parts of a given Bible book or passage. Unfortunately, Northrop Frye’s lament concerning the disintegrative results of the critical approach is too frequently also applicable to the grammatical historical approach used by evangelicals.[49] Too often students of the Bible are trained to treat the text so microscopically in looking for lexical etymologies and syntactical pegs that they never see the grand sweep of the theme and development of the passage and thus have never really come to grips with what God is saying. It is high time for us to allow the contributions of a perceptive literary approach to provide refractive correction to our exegetical myopia so that God’s message may be plainly seen.[50]

Notes

- For further details as to the relationship of MT and LXX in Jeremiah, see F. Geisebrecht, Das Buch Jeremia (2d ed.; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1907) xixxxxiv; R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969) 817–18; Sidney Jellicoe, The Septuagint and Modern Study (Ann Arbor: Eisenbrauns, 1978) 137; Ernst Würthwein, The Text of the Old Testament (4th ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979) 52; and Louis Stulman, “Some Theological and Lexical Differences Between the Old Greek and the MT of the Jeremiah Prose Discourses,” Hebrew Studies 25 (1984) 18–23.

- See F. M. Cross, Jr., The Ancient Library of Qumran (Garden City: Doubleday, 1961) 186–87; cf. J. A. Thompson, The Book of Jeremiah (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980) 118–20.

- For details see John Bright, “The Book of Jeremiah, Its Structure, Its Prophecies, and Their Significance for the Interpreter,” Int 9 (1955) 259–78; W. L. Holladay, “Prototype and Copies: A New Approach to the Poetry-Prose Problem in the Book of Jeremiah,” JBL 79 (1960) 351–67; John Bright, 110WESTM (AB 21; Garden City: Doubleday, 1956) 1vi-1xxxv; Otto Eissfeldt, The Old Testament (New York: Harper & Row, 1965) 348–65; W. L. Holladay, “The Recovery of Poetic Passages in Jeremiah,” JBL 85 (1966) 401–35; M. Kessler, “Jeremiah Chapters 26–45 Reconsidered,” JNES 27 (1968) 81–88; R. K. Harrison, Introduction, 809-17; W. Nicholson, Preaching to the Exiles (Oxford: University Press, 1970); H. Lörcher, “Das Verhältnis der Prosareden zu den Erzählungen im Jeremiabuch,” TLZ 102 (1977) 395–96; G. R. Castellino, “Observations on the Literary Structure of Some Passages in Jeremiah,” VT 30 (1980) 398–408; J. A. Thompson, Jeremiah, 27-50; R. M. Patterson, “Reinterpretation in the Book of Jeremiah,” JSOT 28 (1984) 37–46; and “Repentance or Judgment: The Construction and Purpose of Jeremiah 2–6, ” ExpTim 96 (1985–86) 199–203. One should note as well the several important articles in Leo G. Perdue and Brian W. Kovacs (eds.), A Prophet to the Nations (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1984) 175–246.

- J. Barton Payne, “The Arrangement of Jeremiah’s Prophecies,” Bulletin of the Evangelical Theological Society (Fall 1964) 120–30; B. H. Hall, “Jeremiah,” The Wesleyan Bible Commentary (ed. C. W. Carter; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1968) 3.181-82.

- Otto Eissfeldt, Old Testament, 349-65.

- T. R. Hobbs, “Some Remarks on the Composition and Structure of the Book of Jeremiah,” in a Prophet to the Nations, 184-90.

- G. R. Castellino, “Observations,” 398–408.

- John Bright, Jeremiah, 1xxiii-1xxviii; R. M. Patterson, “Reinterpretation,” 37–46; and E. W. Nicholson, The Book of the Prophet Jeremiah (Cambridge: University Press, 1973) 10–16.

- J. A. Thompson (Jeremiah, 59) is correct in pointing out that “on the whole recent opinion inclines to the view that it is impossible to reconstruct the scroll referred to in ch. 36, although most are agreed that its material is embedded somewhere in chs. 1–25 and probably in the early chapters.” See further the data in n. 46.

- OT scholarship has been prominently affected by the pioneering efforts of B. Duhm, Das Buch Jeremiah (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1901) and especially Sigmund Mowinckel, Zur Komposition des Buches Jeremia (Kristiania: Dybwad, 1914), who saw three types of material inherent in the Book of Jeremiah: (A) authentic prophetical oracles composed mostly in poetry, (B) biographical narratives which Baruch wrote in prose, and (C) autobiographical material written in prose. While many have modified or rejected all or parts of Mowinckel’s thesis, all have had to come to grips with it.

- William McKane (A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Jeremiah [ICC; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1986] 1.xlvii) rightly affirms that “the time has come…to concentrate more on the internal relations of the constituents of the book of Jeremiah and to be less bothered about comparisons between the prose of the prose discourses of the book of Jeremiah and the prose of other bodies of Old Testament literature.”

- Many biblical scholars have observed that the Bible is too often interpreted solely in accordance with Western hermeneutical principles and theological categories and therefore needs to be approached judiciously from the point of view of the Semite as well if a full understanding of the text is to be gained. See, for example, the remarks of R. Laird Harris in his preface to John Lightfoot, A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica (4 vols.; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1979) 1.iii-viii. See also r. Bowman, Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek (New York: Norton, 1970); U. Cassuto, “The Sequence and Arrangement of the Biblical Sections,” and “The Arrangement of the Book of Ezekiel,” Biblical & Oriental Studies (2 vols.; Jerusalem: Magnes, 1973) 1. I6 and 227–40; R. Longenecker, Biblical Exegesis in the Apostolic Period (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1975). To the contrary, see the remarks of D. A. Carson, Exegetical Fallacies (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1984) 44–45.

- For example, although Mowinckel’s type A falls largely within the early chapters of Jeremiah and his type B is clustered largely in chaps. 26–29 and 34–45, neither case is that completely established. Moreover, type C is scattered almost randomly throughout the book. Thus, R. K. Harrison (Introduction, 815) is doubtless correct in observing, “Despite the prolonged history of criticism of Jeremiah, it is evident that scholars are far from being in agreement as to the nature of the process by which the prophecy acquired its extant form…. One thing is sure, namely, that the history of its composition and growth is not to be explained entirely on a purely literary basis.”

- R. K. Harrison (Jeremiah and Lamentations [Tyndale; Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity, 1973] 32) remarks, “While it is true that the prophecy in its final form constitutes an anthology of the utterances of Jeremiah, it is clear that the latter occur in a quite irregular manner without following any particular chronological pattern, and it is difficult at times to see why some oracles should occur in their present place.”

- See further the discussion of T. R. Hobbs, “Some Remarks on the Composition and Structure of the Book of Jeremiah” (Prophet to the Nations, 184-90).

- John Bright (Jeremiah, 1xxiv) appears to be close to the truth in affirming, “The basis upon which such groupings were made seems for the most part to have been that of common theme, common occasion, or even catchword.”

- Charles L. Feinberg, Jeremiah (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1982) 11.

- A further comparison between the two major units of Jeremiah’s prophecies can be seen in that each introductory section sets forth the theme for that unit and is followed by the prophet’s plea for the people’s repentance. Thus, the following schema emerges: chaps. 2–24 chaps. 25–51 Theme 2:1–3:525:1–38 Preliminary Plea 3:6–4:426:1–6 Development 4:5–23:4026:7–51:58 Concluding Sign 24:1–1051:59–64

- Among the many examples of literary bookending in the Scriptures, note Ezekiel’s dumbness that encloses the prophecies of chaps. 3–24 and serves as an introduction to chaps. 33–39. His commissioning as a watchman to Israel (chaps. 3; 33) serves a similar process. One may also compare Nah 2:1 (Heb. 2:2) with 3:18 where the figure of scattering bookends the description of the doom of Nineveh. Note also the bookending effect of the heading (v 1) and colophon (v 32) in Genesis 10 and the narrative sections in Leviticus where chaps. 810 and 16 bookend the laws of uncleanness (chaps. 11–15). See further the remarks of Gordon J. Wenham, The Book of Leviticus (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979) 161–62, and R. D. Patterson, “The Song of Deborah” (Tradition and Testament: Essays in Honor of Charles Lee Feinberg [eds. John S. Feinberg and Paul D. Feinberg; Chicago: Moody, 1981] 142). For the principle of poetic chiasm, see Robert L. Alden, “Chiastic Psalms: A Study in the Mechanics of Semitic Poetry in Psalms 1–50, ” JETS 17 (1974) 11–28. Note that Robert Althann (A Philological Analysis of Jeremiah 4–6 in the Light of Northwest Semitic [Rome: Biblical Institute Press, 1983] 310) considers chaps. 4–6 to be a “somewhat loosely integrated unit” and finds several bookending devices in 4:1–4 and 6:29–30. Although Althann makes a good case, the heading at 4:5 (see p. 3) and the seemingly obvious hooks in 4:4 and 4:5 (see p. 11), as well as the thematic harmony of 4:1–4 with 3:6–25, all of which deal with God’s pleading with his people, appear to this writer to favor the more usual association of 4:1–4 with what precedes rather than that which follows. See further the suggestion of W. L. Holladay given in n. 45 below.

- H. Van Dyke Parunak, “Transitional Techniques in the Bible,” JBL 102 (1983) 540–41.

- Ibid., 530-32.

- John Bright, Jeremiah, lxxiv.

- William McKane, Jeremiah, lxxxiv.

- R. D. Patterson, “A Multiplex Approach to Psalm 45, ” Grace Theological Journal 6 (1985) 43 n. 59.

- U. Cassuto, Biblical & Oriental Studies, 1.228. Elsewhere (ibid., 1.1-6) Cassuto points out the value of this literary device as an aid for memory and suggests that by understanding this technique one will be kept from the “conjectural emendations or rearrangements of the sections” (p. 1) of misguided critics. Cassuto goes on to demonstrate the employment of hooks in vast sections of the OT including Leviticus, Numbers, Canticles, and Isaiah. He points out their usage in the arrangement of the Book of Ezekiel and suggests that this principle may even account for the canonical order of the Minor Prophets.

- That such is the case may be seen in that although chap. 25 sets the theme for 25–51, the first portion of the chapter (vv 1–14) reiterates God’s previous case against Judah, thus looking back to chaps. 2–24, while vv 15–38 clearly look on to the end of the book.

- Although a full study of the subject is beyond the scope of this paper, the writer believes that the principle of hooks can be profitable in discerning still smaller segments within the book, perhaps even the perimeters of the individual Jeremianic oracles. Preliminary observations with regard to some of these will be given in the footnotes that follow.

- The basic theme of 4:5–6:30 is the prediction of the coming invasion of Jerusalem from the north (cf. 4:5–8, 11–13, 15–17; 5:10–17; 6:1–8, 22–23). At least three distinct groupings can be discerned, 4:5–31; 5:1–31; and 6:1–30, each of which is linked together with a literary hook: “look” (4:23, 26; 5:1) and “(this/my) people” (5:10, 14, 19, 23, 26, 31; 6:14,19, 21, 22, 26, 27). Chaps. 5 and 6 appear to admit of subdivisions along the same principle.

- The section 7:1–10:25 doubtless contains many shorter oracles dealing with the sins of the people of Judah and Jerusalem. The key term “people” occurs some fifteen times in these chapters, further accounting for their juxtaposition to 4:5–6:30 (see previous note). In accordance with the details of subject matter, literary form, and catchwords, the following subdivisions seem certain: 7:1–8:3, a prose account dealing with the judgment of God’s idolatrous people; 8:4–9:26, detailing the grievous wound of Cod’s people (8:11, 22) and their ruin (the term “my people” occurs eight times in this portion); and 10:1–25, recording the idolatrous folly that brought on Israel’s judgment (note the hook “nation” in 9:26; 10:2, 7, 25).

- The section 14:1–17:18 doubtless contains several individual pronouncements. The theme of remembering occurs frequently in these verses (14:10, 21; 15:15; 17:2). At least the following subdivisions may be discerned: 14:1–15:4; 15:5–21; 16:1–21; and 17:1–18. These appear to be clearly established by means of the hooks “sword” (14:12, 15; 15:2, 9), “mother/birth” (15:10; 16:3), and the theme of God’s judgment by the coming exile (16:13; 17:4). It could be that still further segments are discernible on the basis of the so-called “confessions” of Jeremiah (15:10–21; 17:12–18; cf. 18:1823; 20:7–12, 14–18) and other stylistic and thematic considerations.

- The theme of forgetting and remembering, interrupted by the discussion of the Sabbath (17:19–27), reappears in chap. 18 (vv 15, 20). Chaps. 18, 19, and 20 probably represent at least three subdivisions. Chap. 19 begins with an imperative, as does chap. 18, and like the previous chapter deals with the lessons learned from the potter. “Disaster” becomes a hook for chaps. 18 and 19 (18:11, 17; 19:3, 15). Chap. 20 is probably linked to chap. 19 simply because it took place at that particular time (cf. 19:14–15 with 20:1–2).

- The pericope in 23:1–8 is doubtless a separate segment positioned here to form a stark contrast with the false shepherds (Judah’s kings) whom Jeremiah has considered in 22:1–30 before moving on to still other false leaders (the prophets) in 23:9–40. In contrast to a people whose unrighteous leaders will bring on the exile of the nation, Cod will raise up a righteous branch who will rule over a redeemed people that will be restored to its land and the place of blessing.

- The theme of disaster will also occur in the hinge chap. 45 (45:4). It is also interesting to note that just as the denunciation of Egypt begins the discussion of the judgment of the foreign nations in chap. 25, so the section concerned with the foreign nations prophecies (chaps. 46–51) is initiated with the judgment of Egypt (46:2–28). All of this demonstrates that chap. 25 is intimately connected with the latter half of the Jeremianic collection (chaps. 25–51).

- Although the respective divisions in chaps. 27–29 appear to form natural subdivisions concerning incidents in this period of Jeremiah’s life, the closely related subject matter of chap. 26 (despite the differences in time designation; cf. 26:1; 27:1; 28:1; 29:1–2) may allow chaps. 26–29 to be grouped together under the title “The Book of Controversy.” Indeed, the prophecy of the seventy years of captivity (25:8–14; 29:1014) may provide a further hook associating the introductory chapter (25) with the following segment (chaps. 26–29).

- The common themes of the new covenant, the return from captivity, and the restored fortunes of Israel in chaps. 30–33 have led many to view these four chapters as one segment known as “The Book of Consolation” (e.g. Thompson). Others (e.g. Horace D. Hummel, The Word Becoming Flesh [St. Louis: Concordia, 1979] 252) stress the fact that chaps. 32–34 are placed in the time of the siege of Jerusalem (c. 588 BC) and link these chapters closely together. One might include also chap. 35 and see a common theme of loyalty and disloyalty in the face of critical times running through chaps. 32–35 and entitle the segment "The Book of Crisis." In any case, a closeness of theme, subject matter, and keywords accounts for the precise order of chaps. 30–36 and for their being placed after chaps. 26–29 and before those chapters dealing with the fall of Jerusalem (chaps. 37–39) and its aftermath (chaps. 40–44).

- The pericope 34:1–7 has probably been prefixed to 34:8–22 because of its setting in the days of King Zedekiah (34:2, 4, 6, 8, 21). A common hook with the previous two chapters may be found in that they, too, are dated to the reign of Zedekiah (cf. 34:1 with 34:2; 34:8).

- Egypt is probably placed first in the list of foreign nations to be judged both because its judgment was mentioned (44:29–30) just before the hinge chap. 45 and because Egypt was the first nation to be denounced in the theme chapter with which the whole unit is introduced (25:19).

- The fact that this section (chaps. 46–51) begins with a thematic heading (46:1), has a unifying theme of judgment, and ends with a sign (51:59–64) may indicate that these oracles were initially grouped together as a separate collection.

- See above, p. 118.

- The different arrangement of the LXX text with regard to the foreign nations prophecies was noted in the introductory remarks (see above, p. 109). The present order of MT is defensible, however, not only on the basis of the fact that chap. 25 serves as the thematic introduction to the whole unit (chaps. 25–51); by approaching the subject of the foreign nations as the last item in the statement of the theme, it also allows God’s judgment of the nations to form an inclusion bookending the whole unit (25:15–38; 46:1–51:64). The very separation of the portions dealing with the foreign nations, rather than being a matter for critical perplexity (see Leo C. Perdue, “Jeremiah in Modern Research: Approaches and Issues” [A Prophet to the Nations, 13-14]), can be seen to bear doubly the marks of deliberate design. T R. Hobbs (A Prophet to the Nations, 184) also notes the parallel order of subjects in the two portions dealing with the judgment of the foreign nations.

- See n. 26.

- C. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, Biblical Commentary on the Prophecies of Jeremiah (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1956) 1.29. See also n. 47.

- T. R. Hobbs, A Prophet to the Nations, 190. Thus John Bright (Jeremiah, lxxvii) perhaps is overly pessimistic in remarking relative to the compiling and final arrangement of Jeremiah’s prophecies, “How, and when, all this was added to the basic Jeremiah collection, and why it was added in the order that it was, are matters of well-nigh pure speculation.”

- It may prove to be the case that a chronological reconstruction is not wholly beyond the realm of possibility. Note the preliminary efforts of J. Barton Payne, “The Arrangement of Jeremiah’s Prophecies,” Bulletin of the Evangelical Theological Society, Fall (1964) 120–30; and E. J. Young, An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1953) 225–29. Nevertheless, such a task is beyond the scope of this paper.

- Several smaller collections doubtless have contributed to the three larger sections (chaps. 26–35; 37–44; 46–51) in this unit (e.g. chaps. 26–29; 30–31; 32–35). W. L. Holladay (The Architecture of Jeremiah 1–20 [Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1976] 27) suggests that 1:5 and 20:18 form an inclusion. If Holladay is correct this may indicate an early stage in the collecting process. It would also be further evidence of bookending in Jeremiah.

- While speculation in such matters as the extent of the material in Jeremiah’s original scroll and that which constituted the reissued second edition, the steps and stages of collection in the compilation of the scroll, the precise dating of many of the prophecies recorded in the book, and the amount of involvement of Baruch in the writing or compiling of the final Jeremianic corpus may be of importance and/or scholarly interest, in the final analysis full certainty eludes all such endeavors. William McKane (Jeremiah, lxxxvi) sounds a cautious note with regard to the first problem that may well apply to all such efforts, “It does not seem to me that there is any way of arbitrating effectively between the various estimates of their respective contents, and at the end of the day one can do little better than take refuge in agnosticism.”

- Such also is the verdict of the careful analysis of the prose portions of Jeremiah by H. Weippert, Die Prosareden des Jeremiabuches (BZAW 132; Berlin: de Gruyter, 1973). It should also be observed that the investigation undertaken here has yielded results similar to those studies which have found that many of the canonical books are arranged in a bifid structure displaying deliberate design between two parallel halves. See, for example, the insightful studies by William Hugh Brownlee, The Meaning of the Qumran Scrolls for the Bible (Oxford: University Press, 1964) 236–59; R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1969) 787–90; James S. Ackerman, “Satire and Symbolism in the Song of Jonah,” Traditions in Transformation (eds. Baruch Halpern and Jon D. Levenson; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1981) 213–46; Stephen Brown, “Structured Parallelism in the Composition and Formation of Canonical Books: A Rhetorical Critical Analysis of Proverbs 10:1–22:16, ” Paper presented to the Thirty-Fourth Annual National Meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society; and David W. Gooding, “The Literary Structure of the Book of Daniel and its Implications,” TynBul 32 (1982) 43–79. Gooding (p. 66) argues forcibly that such careful structural design suggests original authorial intention rather than the impress of later editorial redaction. Note that F. Cawley and D. R. Millard (“Jeremiah,” The New Bible Commentary [ed. Donald Guthrie; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970] 628) have divided Jeremiah in bifid fashion.

- Young, Introduction, 229. Note also the remarks of C. Hassell Bullock (An Introduction to the Old Testament Prophetic Books [Chicago: Moody, 1986] 203), “My assumption is that the material comes from Jeremiah, most likely through the hand of his scribe Baruch, unless it can be proved otherwise. As a review of modern scholarship on the subject reveals, that process of proof is often subjective and prejudiced against the prophet. Of course, the charge can be made in the other direction, and sometimes justifiably so. Yet the assumptions upon which many critical scholars approach the prophets are based upon those materials that they will allow to these biblical spokesmen.”

- Northrop Frye, The Great Code (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982) xvii.

- To this end it is gratifying to note the recent appearance of books that give proper consideration to matters of literary analysis, for example Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1982); Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative (New York: Basic Books, 1981) and The Art of Biblical Poetry (New York: Basic Books, 1985); Leland Ryken, Words of Delight (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987) and Words of Life (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987); Tremper Longman III, Literary Approaches to Biblical Interpretation (Foundations of Contemporary Interpretation 3; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1987); and Robert Alter and Frank Kermode (eds.), The Literary Guide to the Bible (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1987).

No comments:

Post a Comment